During its 14-week run at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the exhibition Van Gogh: Up Close sold an extraordinary number of tickets to visitors from every state in the union and 46 other countries and territories. The only other North American venue for the exhibition is the National Gallery of Canada, where it opened on May 25, the first serious showing of Van Gogh’s work in Canada in a quarter century. It is expected to be the blockbuster art show of the summer, attracting tourists and art obsessives from across the country and around the planet.

The success of this exhibition is no anomaly. Wherever and whenever his paintings are shown, Van Gogh draws the sorts of crowds that are the almost exclusive preserve of geriatric rock and roll superstars like Bruce Springsteen and the Rolling Stones.

For most of his life, Vincent Van Gogh was impoverished, physically unwell and mentally unstable. After two of the most gloriously productive years of any artist in any medium, on a summer’s day in France in July 1890, he shot himself in the chest with a revolver, dying of infection a day later. His last words, according to his brother Theo, were “The sadness will last forever.”

So why does Van Gogh transfix us still?

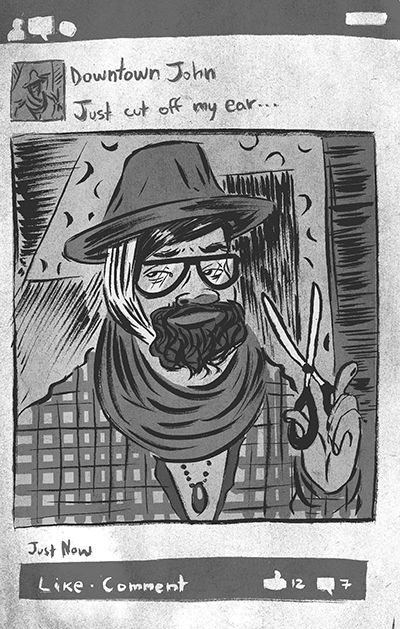

Oleg Portnoy

Certainly, the paintings are extraordinary. A typical reaction is a New York Times review of Van Gogh: Up Close, which describes nature captured by an almost ecstatic vision—paintings “roiled of surface, ablaze with color and steeped in feeling.” Even the works that should have long turned to cliché or become dulled with familiarity through over-reproduction have the power to stop us in our tracks.

Then there is his life, which remains a biographical rubbernecker’s dream: the poverty and illness, the star-crossed love life, the commercial frustration, the mutilated earlobe. For better or for worse, the life of Vincent Van Gogh provided the narrative template for every tormented poet, writer and rock star who came after.

But there has to be more to it than the pretty pictures, and far more to it than the tortured artist shtick. Vincent Van Gogh sold a single painting in his lifetime, Red Vineyard at Arles, for 400 francs (about $1,000 in today’s currency) but by the end of the millennium three of his paintings—Sunflowers, Irises and Portrait of Dr. Gachet—had set successive records for the highest price for a painting sold at auction.

As Modris Eksteins argues in Solar Dance: Genius, Forgery and the Crisis of Truth in the Modern Age, to understand Van Gogh, and our reaction to his work, is to understand the cultural warp and political weft of the 20th century. It is to understand the fall of the Weimar Republic and the rise of the Third Reich, the birth of the counterculture and the death of communism, and—not least of all—the great flourishing of celebrity culture and our obsession with the who of art, not the what. In sum, Eksteins writes: “Van Gogh is ours. We are Van Gogh.”

At the thematic core of this incredibly original, erudite and ambitious book is the notion of authenticity. The term comes to us from the fields of art history and museum studies, where the question of authenticity refers to a work’s history or provenance. To ask whether a work or object is “authentic” is to ask whether it is what it appears to be—a Ming vase, a Rothko painting—and, therefore, whether it deserves the veneration that it appears to demand, or if it is worth the price that was paid for it.

The problem of appearance versus reality, between how something seems and what it actually is, was for centuries a staple of arcane philosophical debate, but it transmogrified over the course of the 20th century into the moral and aesthetic touchstone of our time. We marvel at someone who exhibits an “outer” control that masks an “inner” turmoil, we talk about friends who are “shallow,” or “superficial” in contrast with those who are “deep” or “profound,” and we search for meaning in a world that seems increasingly alienating and indifferent. In all these cases, we are invoking the jargon of authenticity.

As Lionel Trilling pointed out in Sincerity and Authenticity, the reason authenticity became so central to our moral slang is that it alerts us to “the peculiar nature of our fallen condition, our anxiety over the credibility of existence and of our individual existences.” The biblical characterization is deliberate: the search for authenticity is driven by the desire for meaning in a world where all the traditional sources—religion, caste, ethnicity, ideology—have lost their legitimacy. The question of authenticity is nothing less than a response to the crisis of modernity, where all that is solid melts into air and all that is holy has been profaned.

Van Gogh claimed he was seeking an inner truth through art, a quest that put him firmly within the romantic reaction to the scientistic, rationalistic, Enlightenment. The modern dilemma arises when authenticity (“inner truth”) replaces facts (“outer truth”) as the fundamental source of knowledge. And so it is fitting that Eksteins situates Van Gogh as the 20th century’s great avatar of authenticity. Under that concept’s ever-expanding brow he gathers a starry night of contrasting notions: the real and the fake, the genuine and the fraudulent, the original and the copy. Put these together, and you get the threefold crises of our time: of truth, identity and legitimacy, all conspiring and contending in the roiling cauldron of modernity.

As Eksteins points out, Theodor Adorno described art as the religion of the bourgeoisie, and he has structured his narrative as something close to a religious parable, with Van Gogh as something close to a Christ figure. Close to? Eksteins quotes the art critic Julius Meier-Graefe, who in 1914 wrote, “Van Gogh was the Christ of modern art … He created for many and suffered for many more.” After an exhibition in 1927, another critic described Van Gogh’s life as “a martyrdom, an unbroken chain of trouble and humiliation.”

Yet every Christ figure who appears on the scene is an invitation to the false prophet who performs all manner of counterfeit miracles. In Eksteins’s parable, the anti-Christ arrives in the form of Otto Wacker, a self-styled German art dealer, a vagabond whose previous career was as a dancer who performed Spanish folk dances with his sister under the stage name Olindo Lovael.

In 1925, Wacker claimed to have come into possession of 33 previously unknown Van Gogh paintings. His story was that he was acting on behalf of a shadowy Russian aristocrat who had moved the paintings to Switzerland, and who had to remain anonymous out of fear of persecution by Soviet authorities. Wacker’s story was not as implausible as it sounds: there were very few reliable records for many of Van Gogh’s works, and while he was alive Van Gogh had a habit of giving his paintings away or trading them with other artists. There were also reports of huge stacks of Van Gogh’s canvasses lying abandoned in various attics.

And so despite the complete absence of any proof of provenance, a number of highly regarded art dealers and Van Gogh experts gave their stamp of approval to the Wacker Van Goghs. These included Meier-Graefe, Hendrick P. Bremmer and Jacob-Baart de la Faille, the last of whom was in the midst of completing a catalogue raisonné of Van Gogh’s work. This prompted a number of major galleries to purchase some of the Wacker paintings, despite ongoing concerns about their origins.

In 1928, an exhibition of the Wacker Van Goghs was mounted at Paul Cassirer’s gallery in Berlin. The show was designed to coincide with the publication of de la Faille’s catalogue, but things went off the rails when many of the paintings were quickly denounced as outright fakes. Wacker was charged with fraud, and eventually put on trial in 1932. He was convicted and, after an appeal, sentenced to 19 months in prison and ordered to pay a stiff fine.

In Eksteins’s hands, the themes of Otto Wacker’s trial—the triumph of illusion over reality, of self-interest over expertise, of illusion over art—are symptomatic of the collapse of Weimar’s “republic of reason” and the rise of Adolf Hitler, with his pidgin appropriation of “authentic” German motifs. The fact that Otto Wacker, after his trial but before his imprisonment, went on to join the Nazi party only amplifies the parallels.

Yet if the trial of Otto Wacker symbolizes the more general failure of the Weimar Republic, then, as Eksteins sees it, the rise and fall of Weimar is itself a compressed version of the entire narrative of the 20th century:

The disenchantment that overwhelmed Germany in the wake of the Great War had subsequently spread to the West as a whole, as had the need to improvise beyond the confines of inherited ideology and morality. The Weimar aesthetic had turned into the Western aesthetic; the Weimar mood had become our mood. Our own quest for identity and purpose often echoed that of Weimar.

Some of this material is painted in strokes that are a bit too thick. At times, Eksteins seems concerned that the reader has not quite bought his thesis, and especially in the book’s closing pages, he piles on the references and the allusions, trying to show that virtually everything that has happened since is little more than a cheap imitation of the original. Fritz Lang and Marlene Dietrich, Albert Einstein and Werner Heisenberg, Grace Slick and Johnny Rotten, the soixante-huitards in Paris and the student riots in Chicago in 1968: “Such is the legacy of Weimar,” writes Eksteins. “And such is the legacy of Vincent Van Gogh.”

Eksteins need not have tried so hard. While it might be a bit of a stretch to shoehorn everything into the Weimar framework, there is one crucial sense in which he is absolutely correct: Van Gogh’s turn away from external sources of solidity in the form of facts, truth and reason, looking inward in an attempt to anchor authority in the unmoved mover of the creative self, is (to return to biblical themes) our culture’s original sin. And while it might not have given us Adolf Hitler, it has delivered us into the hands of George W. Bush, Fox News and the Tea Party (not to mention the bleached versions of the same we have imported here into Canada).

Once upon a time, political leaders had to have a handful of key virtues—courage, intelligence, magnanimity, decisiveness. Now, all we care about is “authenticity.” As the New York Times columnist David Brooks likes to put it, Americans will always vote for the candidate they most want to have a beer with, which is why Mitt Romney hasn’t a hope of beating Barack Obama. But this obsession with authenticity, and the question of whether our leaders are being “true” to themselves and “transparent” to the public, is just the Vincent Van Gogh/Otto Wacker dynamic playing out on the political stage.

When the satirist Stephen Colbert coined the term “truthiness” to describe American political discourse, he defined it as “‘what I say is right, and [nothing] anyone else says could possibly be true.’ It’s not only that I feel it to be true, but that I feel it to be true.” His point is that, by universal consensus, we no longer care about the facts or the external truth of the matter. What we care about is emotional truth and the politics of perception over reality. Not truth, but truthiness.

At his trial, Otto Wacker wondered why he was the one in the dock. After all, a number of experts had authenticated his paintings. Highly respected dealers had purchased them. And now he alone stood accused of visiting a fraud upon society. As Eksteins notes, there was considerable support for Wacker on this point amongst the general public. After all, by leaving behind the external world and turning inward for more subjective ecstasies, Van Gogh had, according to one observer, “upset a long-standing balance and moved not toward but away from truth, in the direction of distortion and falsehood … it was not Wacker who was guilty, but Van Gogh himself!”

With the wisdom of hindsight, we can now see that the whole culture was out of order. Van Gogh and Otto Wacker, the artist and the fraudster, are merely two ways of looking at the same problem, which is that the modern world has come unanchored. In the book’s last lines, Eksteins writes “As we copy and digitize sans cesse, as our technology of reproduction obliterates any sense of permanence and constancy, the fraudster merges with the artist, and in the process all chance of authenticity may be lost.”

Eksteins is content to stop there. He leaves dangling the next step in the argument, namely that the search for authenticity is the cause of our problems, not the solution to it. Nor does he appear to seriously confront the thought that any resolution to the crisis of modernity might require that we stop thinking in the terms and the categories that Van Gogh has given us.

But maybe that is what we ought to do. Maybe what we really need is to stop sailing around plumbing our individual creative depths, weigh anchor and re-engage with the external world. Start taking things like facts, truth and reason more seriously, instead of treating them as quaint intellectual relics from a more naive time.

Modris Eksteins has written a marvellous, brilliant book, one that gives a clearer understanding of our cultural moment than just about anything published in ages. But it is symptomatic of how lost we are that the one thing not on offer, in a book called Solar Dance, is enlightenment.

Andrew Potter wrote The Authenticity Hoax and, with Joseph Heath, The Rebel Sell.