In the spirit of the often personal and doubt-filled essays in this collection, a confession: I am no longer sure about this stuff either. Literary traditions, canons, the way of being in the world, via books, established over the past three centuries, the great 20th-century literary life, the challenging but rewarding career that many of us signed up for, even simply the enriching conversations, including ones in this publication, engendered by a healthy book culture—I just do not know. Two decades ago, had the worry been expressed to me, I would have retorted with smug conviction that the Fortress Literature, with its high ramparts and wide moat, would repel all assailants. Ten years ago, I would likely have clung to the view that the Digital Siege might well prove long and bloody and inflict serious damage, but the House would stand.

Now I am doubtful. In fact, I am certain that the majority of people of my age and up—I am 53—are increasingly of the view they will have to carry on deeper into the 21st century with that great culture, those great books, tucked into their cultural pockets, so to speak, for private, semi-nostalgic enjoyment. They are resigned to the ongoing shift, while their/our children and grandchildren are for the most part unaware of any way of being in the world before the digital paradigm launched its heavy tectonics (in 1995 or ’96, apparently, when email went truly mainstream). It seems that “we”—always a presumptuous pronoun, I realize—love our new technologies, each and every one, and are only too happy to follow their leads on the mediums by which we should enjoy our art and entertainment and hold our conversations, public and private alike. Needless to say, as per Marshall McLuhan, who, along with Northrop Frye, may be the most frequently cited avatar in The Edge of the Precipice: Why Read Literature in the Digital Age?, edited by Paul Socken, those mediums become, if not the entire message, then a major aesthetic determinant in the art and entertainment itself, as well as in those conversations. Digital culture is not simply a new means of transmitting data. It changes what is being transmitted and it changes—does it ever—those involved in the exchanges. Transmission, transformation, even transmutation: the digital age retails the ultimate “bundle,” to use the language of the new local fortress lords, the Rogers, Bells and Shaws.

So “we” are collectively discovering what the American author Sven Birkerts calls “the digitizing of almost every sphere of human activity,” and it is coming as a shock. And yet, many of the transformations were forecast a couple of lesser shifts ago. Those almost mythic days at the University of Toronto, when Frye and McLuhan roamed the campus issuing startling and still surprising conjectures about our unfolding destinies as creatures of electricity, are a long half-century in the past. Artists the stature of George Orwell, Philip K. Dick, J.G. Ballard and Margaret Atwood have been anticipating our souls being mapped and remapped by technology since, more or less, the onset of television. Even the less noisy demise of book culture was declared well underway before that mid-1990s drop-dead date. Birkerts suggested as much in his celebrated 1994 book The Gutenberg Elegies, whose subtitle “The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age” could easily work for The Edge of the Precipice as well. Canadians may remember Alberto Manguel’s 2007 Massey lectures The City of Words, in particular the final lecture, with its angry regret at how literature is faring in the brave new corporate publishing world.

Either we have known all along what was coming and did not pay attention, or—my own hunch—we could not wait for it to happen. We could not wait to be dialled in, to get connected, to become part of the grid. And now we are all those things, and the kind of watching, reading, talking, thinking, acting, even dreaming, we prefer to do is bound up by the means that we do it.

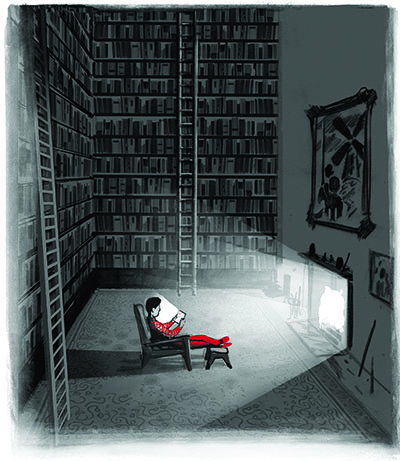

Miko Maciaszek

In short, it may be over, or nearly so, for some of those pre-shift cultures, including, if not especially, one as slow, demanding and burdened by its own history as literature. How the mighty have fallen. How easily, too, has the past been shucked off, found unappealing by everyone from editors to consumers to humanities faculties at universities. From its doom title to its all-or-nothing subtitle—not an instructive “how” to read literature in the digital age, but a “why” with a question mark—this new collection of essays stakes its discursive ground in the current uncertainty. And yes, you either have to buy the book to read about the precarious state of books, a hefty $29.95 in an age of endless “free”—or, more likely, pirated—content, or else hope against hope that your library, perhaps recently retitled an “information centre,” actually stocks it. Luckily, an electronic edition is available.

Paul Socken explains the title in his introduction. It comes from an F. Scott Fitzgerald essay, and Socken, a retired University of Waterloo professor of French, suggests that reading literature in the new century is “like sitting at the edge of a precipice, glimpsing new vistas while remaining precariously connected to one’s familiar surroundings.” He tasked his contributors to explore the following: “what precisely is it that reading literature—even in our wired world of social networking, blogging, tweeting, Google, Wikipedia and so on—brings us?”

Socken’s preliminary thoughts are spirited, drawing on Frye’s influential 1963 Massey lectures, The Educated Imagination. He reiterates many core humanist principles for art, including its happy lack of utility and its wider purpose, quoting Frye, to help us envision “the society we want to live in.” Northrop Frye’s insistence on moral frameworks for systems, be they literary or social, often seemed in quiet contrast to McLuhan’s more “cool” and floating observations on how technology transforms everything in its path. For generations of thinkers and educators, Frye’s humanist underpinnings to reading literature were a given, evidence of a strong foundation upon which western civilization firmly stood. (The problematic McLuhan was generally passed over in silence.) Sure enough, Shakespeare, Dickens, Coleridge, Shelley, Samuel Beckett, even Kenneth Clark’s Civilization are all cited by Socken in defence of the importance of literature, “then or now.”

Almost half of The Edge of the Precipice is given over to variations on this theme: academics, mostly senior, explaining why books meant so much to them, largely in a pre-digital context, and bemoaning their state in the digital one. “Cold Heaven, Cold Comfort: Should We Read or Teach Literature Now?” by the esteemed J. Hillis Miller, is the most compelling, if only for its awareness of the privilege and inequality that underwrote many of the “good old days” in (male) academia, and for its paint-stripping conclusions. “The conviction that everybody ought to read literature because it embodies the ethos of our citizens has almost completely vanished,” he writes of the humanist argument. As for the “Arnoldian view of the benefits of literary study,” it is, according to Miller, “pretty much dead and gone.” And that, it seems, is that.

Of deeper interest, if even less comfort to those of us with skin in the old literary game (if not the Arnoldian view), are the contributions of Sven Birkerts and Mark Kingwell. Birkerts, widely admired for his warm generalist explorations of American letters, cites with mordant satisfaction the latest neuro-scientific findings on the act of reading. Accepting that “there may not be such a thing as mind apart from brain function,” he wonders if our larger perceptions of reality—those archetypal stories we humans must tell, as per the understanding of everyone from Homer through to Frye—are not simply narrative projections “engendered by infinitely complex chemical reactions.” Even our capacity for metaphor may be “something that the brain does when complexity renders it incapable of thinking straight.”

If this is true, our sense of agency as readers is essentially false, and as swimmers in the perpetually over-stimulated digital seas we may now be fated, by involuntary neural function alone, to forever skim surfaces, to never really focus, to no longer be capable of the contemplation and concentration required to read our own literary canon. We are out of sync, in effect, with the rhythms of how serious books were created in the age of analog. In a nicely crisp phrase, Birkerts speculates that the triple-decker Victorian novel was “synchronous with the basic heart rate of its readers.” That may no longer be possible, given the accelerated current beats per second.

For the University of Toronto philosopher Kingwell, a better way of understanding the digital age is less to bemoan the passing of liberal humanism, embodied in 20th-century notions of literacy as a driver of democracy—that is, the contents of those morally instructive books we no longer (can) read—than to reflect on the possibility that we are actually evolving into “anti-humanist” beings. Briefly, anti-humanism supposes that individuals are “constructions of subjectivity” who occupy, fleetingly, endless fields of discourse in pursuit of an elusive “self.” The act of reading, ironically, is how we most easily construct that self, however delusional it may be. “There is no self without reading,” Kingwell writes, “because without the discourse that reading underwrites—apt word!—there is no idea of self at all.” We may be in a period of “evolutionary transition” from a humanist to an anti-humanist world, with digital technology aiding and abetting our ontological makeover.

Oh dear. Our brains are increasingly wired out of sync with those analog novels, our illusory identities happily riding the fluid, vast, restless and indeterminate digital highway in search of a self—there is scant consolation among these more probing conjectures. Look backward, look forward or even simply navel-gaze in self-pity, and the consensus among contributors to The Edge of the Precipice is pretty much the same: we are not staring out from the cliff edge of profound change so much as watching the ground crumble beneath us, a collapse suitably heedless, remorseless and fast.

The collection is notably lacking two types of voices. Most battles for book readers—that Fortress Literature alluded to earlier—are initially fought in high schools, where teenage minds are, in the right teacherly hands, open to being surprised and awed and, perhaps, enlisted. English lit classrooms in Canada have endured their own sieges of late, with the enemy frequently their muddled superiors, who have proven disappointingly quick, if not downright keen, to sneak out the back gate before the battle even got real. Reports suggest the fight is ongoing, with many capable and ardent soldiers on behalf of The Catcher in the Rye, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Obasan and so on. A report from the field would have been welcome.

The second absence is writers, in particular the creators of those nearing-obsolescence tomes. As a group, novelists are discussed from on high in The Edge of the Precipice, as though they are already vanished—a hill tribe who, having failed to adapt, died out, leaving behind artifacts for anthropological study. As a practising novelist who is not feeling quite dead yet, allow me a few thoughts on writing in the digital age. First, a banal one: novelists in 2013 are not likely any more interested in writing a Victorian novel than a Victorian novelist was interested in writing an 18th-century novel. We—and yes, here is a different, and equally problematic use, of the pronoun—are interested in writing 21st-century novels. Mark Kingwell, for instance, grounds his anti-humanism conjectures not in the prophesies of a Cyber guru but those of a novelist. Tom McCarthy, whose 2010 novel, C, was short-listed for the Booker prize, expresses his sense of the current form succinctly: “the more books I write, the more convinced I become that what we encounter in a novel is not selves, but networks.”

Second, a certain kind of writer is hoping, whether she or he even thinks about it, to produce a novel that will speak to all ages, societies and shifts. Alberto Manguel, also a practising novelist, has a typically elegant essay in The Edge of the Precipice. “The End of Reading” offers a celebration of the very beginnings of the form—Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote, first published in two volumes between 1605 and 1615. As anyone who has engaged with this endlessly inventive, restless, protean work can attest, Don Quixote is an age-shifter, moving with uncanny ease between the centuries, permanently fresh, edgy and relevant. Only a handful of novels possess that kind of supernal energy—or trickster spirit, perhaps—but the ambition is frequently there.

Finally, novelists in 2013, while certainly chastened and bruised by the ongoing shift, are also interested in it, for the simple reason that “it” is, obviously, of human manufacture, itself a reflection of human desire. “It” is Us, and Us—that is, the human animal—is what novelists mostly write about. On some level, it scarcely matters if those manufactures, those desires, are disastrous on either the largest of scales (the fate of the planet) or a smaller one (the fate of literature in the digital age). Truths so urgent and distressing are indeed very, very interesting, and must be explored. Recent examples of this sophisticated, mildly perverse avidity for disastrous human behaviour, large-scale, include Gary Shteyngart’s Super Sad True Love Story and, just this summer, Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam. By the time this essay appears, more such books will be on the way.

Ironies abound. To end with a ripper, suppose the most cogent and insightful explorations of the fate of literature, the ones that make you think and feel and fill your heart full sore, end up in the pages, paper or digital, of novels that fewer and fewer people want to, or simply will, discover? That will be entirely appropriate. That will be writers trying to synchronize our books to the pulse of the age, hoping against hope we get read while carrying on regardless. Because that is what we do and how we still are in the world, helplessly so. Of this I am, in contrast to much else, sure.

Charles Foran is author of eleven books. He lives in Toronto.