With the Parti Québécois government in Quebec grabbing the centre of Canada’s public policy debate this season with its proposed charter of values, which will apparently seek to ban the wearing of religious symbols by anyone working in the public sector in the province, Mary Anne Waldron’s important new book could not be more timely. In Free to Believe: Rethinking Freedom of Conscience and Religion in Canada, written well before Pauline Marois’s initiative became public, the University of Victoria law professor provides a sophisticated analysis that supports ongoing respect for religious freedom in Canada, subject to principled limits. In an era of mounting skepticism about religious institutions, of increased secularism and of trends toward ever larger numbers of people claiming to be “spiritual but not religious,” Waldron’s work forms an essential aspect of the debate.

The approach in this book is bold but principled. Amid a very complete review of freedom of religion case law in Canadian courts and human rights tribunals, Waldron starts by asserting the fundamental value of freedom. Without freedom, she suggests, the democratic state simply does not survive. In her argument, she stands with this principle even when freedom of religion appears to be in tension with other fundamental Canadian values, like equality rights. She argues for always trying to find ways to reconcile seemingly competing rights so that respect for one right extends only so far that it still makes room for respect for the other.

In making this argument, Waldron takes on some common wisdom concerning Canadian case law on these matters. She discusses literally dozens of cases at length, and interested readers should turn to the book and examine her discussions. But two examples of what her approach means are illustrative. In 2001, the Supreme Court of Canada released its decision in the Trinity Western University case. In this case, the British Columbia College of Teachers was attempting to decline to recognize education credentials from Trinity Western University. It claimed that the school’s moral commitments against homosexual activity, and its community covenant provision under which its students made related pledges concerning their own behaviour, meant that its graduates were not suited to teach in the public school system. The majority of the Supreme Court of Canada disagreed and held that there was no evidence the Trinity Western University graduates would actually discriminate in the classroom. But many legal academics cling to Justice L’Heureux-Dubé’s dissenting judgement, in which she would have ruled against the university. Today, some have argued for applying that dissenting judgement when considering Trinity Western University’s current proposal to open a law school whose graduates would become accredited for legal practice.

Intellectually rigorous as she is, Waldron is actually ready to criticize the majority judgement in the case, although not for its result but for failing to provide workable principles for future cases. The decision claimed to be based on a lack of evidence that the graduates would discriminate. It did not answer what kind of evidence would be enough to lead to decertification of the whole program. Behaviour by one or two graduates? Waldron seeks a more intellectually satisfying framework for the case. She would analyze it in terms of the idea that the assertion of one right cannot depend upon the denial of another. She roots human rights in the dignity of the human person and concludes that each human being must have the same rights. Thus, if one person’s claimed rights deny another’s, there is something wrong with the claimed right. Evangelical Christians’ rights to hold their own personal beliefs while teaching cannot be trumped by the equality rights of students, although students have the right to expect that their teachers treat them fairly and equitably whether or not they agree with their teachers’ beliefs. A conception of each right that leaves room for the other offers a principled approach to the rights conflict.

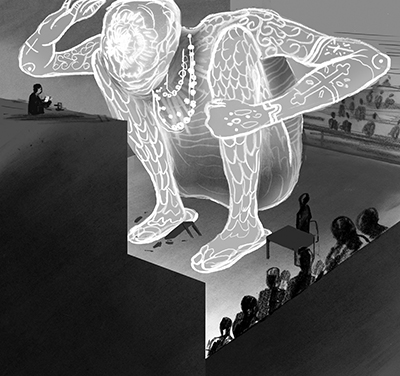

Miko Maciaszek

In 2011, the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal released its decision in the Marriage Commissioners Reference. In this now leading case on whether marriage officiators have a right to decline on religious grounds to perform same-sex marriages, the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal effectively held that the office of a marriage commissioner is a public role and cannot tolerate such exemptions for some marriage commissioners. Technically the court said that there might be a mechanism such as a single intake system where commissioners would be allocated to particular marriages and thus could have exemptions but no same-sex couple would ever face an actual refusal. But, as Waldron highlights, the court did not show much actual support for the single intake system, and the way it described religious rights in the case was limited to a freedom to worship, thus excluding a freedom to manifest beliefs.

Waldron would again approach the case in terms of reconciling different rights. She supports a right to refuse to perform same-sex marriages, based partly on the wide exclusion of many religious marriage commissioners from office that would occur if such a right to refuse did not exist. She also sees it as appropriate to require governments to protect this right to refuse in the manner that is least intrusive against same-sex couples, possibly through a single intake system. But she rejects any trumping of one right by the other, at least in the absence of a decision by legislators. To be clear, she acknowledges that non-discrimination (against gays or any other citizens) is of great importance, even if it means excluding many practitioners from office. But such a decision, according to her, must not be made by courts but by lawmakers.

Here is where matters get more complicated. Waldron’s views do depend on controversial theoretical assumptions that she defends to some extent but maybe not fully enough to convince those who start from other perspectives. Two examples are most pertinent. First, on the role of legislators, she makes the bold statement that “moral choices in which one human right is overridden by another belong to the legislatures alone,” without much further explanation of why this must be the case. It might be appealing to say that legislators should be the ones to make such decisions. But some would argue that the situation where one right is being overridden by another is the very situation when courts need to be ready to protect individuals. Even if the point seems attractive, it needs deeper theoretical explanation to respond to such objections.

Second, on the role of human dignity in supporting a mutual interdependence of rights, Waldron partly draws upon a 1999 equality rights decision of the Supreme Court of Canada that tried to analyze equality rights claims in terms of dignity. However, that dignity-based approach in the case law has been effectively overturned, which leaves her approach to dignity and rights an intellectually appealing one but one for which she presents only a brief argument. In my view, the idea of reconciling rights as a preferred approach to conflicting rights is actually more present in the case law than Waldron lets on, with such a view significantly articulated in the very recent Supreme Court of Canada case concerning whether a sexual assault complainant had to remove her veil while testifying in court because of the accused’s right to face his accuser. (The majority of the court in the case, N.S., sent the matter back to the trial judge with complex instructions on how to approach the rights conflict; the trial judge more recently ruled she had to remove the veil, but a further appeal is pending.) It is important to bear in mind, as Waldron wades through these confusing waters, that she admits she is no political theorist but simply a legal academic making her way through the case law. Political theorists will necessarily play a key role in the acceptance or rejection of the ideas at issue here.

At least some political theorists in recent years have in fact been articulating approaches that are more receptive to religious freedom. Canadian political theorist Charles Taylor, now based at Northwestern University in Chicago, in his epic A Secular Age, both traces the historical roots of modern secularism and ultimately identifies some of the emptiness at its core. His latter chapters suggest that those living within this modern secular age will increasingly be experimenting with new forms of spirituality and that a secular age will yield once again to the ongoing need for religion. Taylor is of course perhaps known among a broader audience as co-author of the Bouchard-Taylor Commission Report on questions of “reasonable accommodation” in Quebec.

The reasonable accommodation debates raised a wide range of questions on the accommo-dation of minority religions and the place of historically majoritarian religions (such as Roman Catholicism) as cultural background. The particular concerns in Quebec, emanating from a place facing cultural-linguistic risk within a largely anglophone North America, often strike those in the rest of Canada as peculiar and, indeed, Waldron does not particularly examine them, as they have generated little of the case law. Of course, if the current Quebec government does proceed to ban public employees from wearing religious symbols, there will no doubt be legal challenges. A European Court of Human Rights judgement from earlier this year, Eweida, upheld the right of British Airways workers to wear religious symbols, and it would be surprising if Canadian courts decided otherwise.

Taylor is not alone among internationally leading political theorists in beginning to turn to topics of religion. Massively influential German philosopher Jürgen Habermas has recently returned to matters of religion with a new sympathy, perhaps founded in a sense that religiously based world views are not going away. In a paper written in 2007, he seeks to articulate new ways in which secularists and religious believers can find common ground and better respect one another in contributions in the public sphere. ((For a full exploration of Habermas’s article, see An Awareness of What Is Missing: Faith and Reason in a Secular Age, published by Polity Press in 2010.))

American legal philosopher Brian Leiter has also weighed in on this discussion with his book titled Why Tolerate Religion? Leiter’s argument is, indeed, that the privileging of religious beliefs over other beliefs is not justifiable. He questions the whole tradition of religious freedom, citing the fact that constitutions and courts show more respect for freedom of conscience if it is based on religious beliefs than if it is not.

Here, Waldron’s book actually serves as something of a riposte. Her whole approach to rights recognizes the importance of imbuing each articulated right with meaning. As a result, she suggests that the reference in Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms to “freedom of conscience and religion” must be interpreted in a way that lets “freedom of conscience” mean something. The courts have not dealt much with this concept. Waldron’s readiness to see it thrive reflects once again her rich conception of rights—all rights.

Where Waldron’s conception will clash most with dominant secularly oriented approaches is in her identification of how courts and human rights tribunals have been tending to give overriding weight to equality even in the face of other rights. They engage in “balancing” tests that invariably override the rights of religious believers. For example, in cases, such as Brockie, involving whether a religious believer who runs a printing service must print materials offensive to his or her beliefs, the “balance” reached by human rights tribunals has been to order the printing. Waldron’s implicit critique of Canada’s human rights tribunals is provocative but rigorous. Those thinking about the issue should take her argument very seriously.

Waldron’s focus is on situations where an individual has clear religious beliefs that he or she puts forward in relation to his or her own conduct. More complicated scenarios arise, of course, when a religious group seeks protection for its practices that have different impacts on different members within the religious group, such as women. This “minority within minorities” problem has begun to receive attention from political theorists in recent years, but Waldron’s focus on the case law means that she does not really grapple with it. There is room for more writing on religious freedom in Canada, and we can only hope Waldron helps to stimulate it.

Despite the presence of many cases raising these issues, matters of religious faith and the importance of protecting it do not always get a lot of attention in Canadian public discourse. Waldron’s book makes a very significant contribution that both guides the reader through a wide variety of case law and articulates provocative views on some of the weaknesses both of the case law and of common approaches to religious freedom in Canada.

Dwight Newman is a professor of law at the University of Saskatchewan. He has written a number of books on constitutional law and rights issues, as well as pieces in such publications as the National Post and Vancouver Sun.