The Government of Canada is not keeping all of the promises it made to aboriginal peoples in 24 “modern” treaties, mostly in the North, negotiated over the last 40 years, ratified by aboriginal peoples and Parliament, and guaranteed by the Constitution of Canada. The Supreme Court of Canada says treaties should “reconcile” aboriginal and non-aboriginal interests, and that the “honour of the Crown” depends upon treaty promises being kept. Certainly the social and economic future of aboriginal signatories rests in large measure on these agreements.

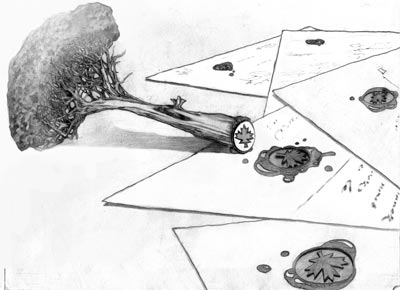

Some modern treaties contain more words than the New Testament. Breathing life and meaning into them requires government transfusions of intellectual and financial resources, and commitments of political capital. Without the needed resources, these modern treaties will never be fully implemented. As years pass and memories of treaty promises fade, these agreements may moulder in the dusty crypts of the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development.

This is an old as well as a new story, for treaty making endures in the bones of our constitution, of Canada’s DNA. Soon after they arrived in North America, the English, French and Dutch made peace and friendship treaties with aboriginal peoples, largely to promote the fur trade. As the British and French competed for the continent, both sought alliances with militarily powerful Iroquois, Hurons, Algonquins, Mi’kmaq and others.

Having won the Seven Years War with France, King George III of Great Britain issued a Royal Proclamation on October 7, 1763, reorganizing the governance of the Crown’s territories in North America and reserving land west of the Appalachian Mountains to the region’s aboriginal peoples. This “gift” did not come from the goodness of the king’s heart but as the result of a pan-tribal uprising in the western Great Lakes led by Ottawa war chief Pontiac. Abusive British soldiers and land-hungry settlers squatting on Indian lands had infuriated Pontiac and his allied chiefs. Pontiac’s military success convinced the Crown to adopt a new policy laid out in the Royal Proclamation that, henceforth, settlers could only legally obtain land from the Crown after the Crown had purchased it from aboriginal peoples through treaties negotiated in good faith and in public.

Gabriel Baribeau

Treaty making continued in British North America following the American War of Independence and in Canada following Confederation in 1867. In exchange for title to their land, 19th-century treaties in Canada provided aboriginal peoples with one-time financial payments or ongoing annuities, reserves, guarantees of hunting, fishing and trapping on unoccupied Crown land, and other benefits. One treaty promised a “medicine chest.”

George Washington characterized the Royal Proclamation as a temporary pacifier to “quiet” the Natives. By making it difficult for settlers to obtain land and slowing the movement west, Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, cited it as one cause of the American Revolution. By 1973 Justice Emmett Hall of the Supreme Court of Canada called the Royal Proclamation the “Indian Magna Carta.” If so, then Pontiac should be feted as a “father of Confederation.”

Canada discontinued treaty negotiations in 1923, leaving huge areas of the country—Yukon, most of the Northwest Territories, northern Quebec, Labrador, British Columbia and portions of the Maritimes—without treaties. Would-be settlers and developers were not rushing north, so Ottawa felt there was insufficient demand for remaining Indian land to warrant more treaties. To keep a lid on claims to land by aboriginal peoples, from 1927 to 1951 the Indian Act made it illegal to raise funds for aboriginal people to pursue such claims against the Crown.

Modern Treaties

The Government of Canada’s dismissive attitudes toward the land claims of aboriginal peoples started to change in the 1950s. In response to a lawsuit by the Nisga’a Indians of British Columbia, the Supreme Court of Canada in 1973 acknowledged the existence in Canadian law of aboriginal title to land regardless of any grant or act of recognition of the Crown. This prompted Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and his minister of Indian affairs and northern development, Jean Chrétien, to offer to negotiate modern treaties with aboriginal peoples who had not signed historic treaties and whose title to land had not been “superseded by law.”

Both historic and modern treaties are rooted in the Royal Proclamation of 1763, but those completed in the last 40 years are far more comprehensive and detailed, and more challenging to implement. Few Canadians appreciate the importance of these modern treaties, which have resulted in Canadian Inuit and First Nations in Yukon and the Northwest Territories becoming owners outright of more land than any other private interest world-wide. The 1993 Nunavut Land Claims Agreement provided for the establishment in 1999 of the Nunavut Territory, almost 22 percent of Canada. Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s push for Arctic sovereignty depends, in part, on implementing this agreement.

Modern treaties are not just land and cash deals; they address land ownership, management of lands and natural resources, harvesting and management of wildlife, assessment of resource development, capital transfers, economic opportunities, royalty sharing, establishment and management of parks and conservation areas, cultural expression and enhancement, and more. In 1995 the government recognized the “inherent right” of aboriginal peoples to govern themselves, and announced its willingness to provide for this in modern treaties. As a result, many of these agreements detail municipal- and provincial-type responsibilities exercised by aboriginal peoples.

It is not all one way. From these agreements Canada gets legal certainty to the ownership of lands and resources, something essential to an energy- and mineral-dependent economy. Modern treaties confirm Crown ownership of 75 percent to 85 percent of the land in modern treaty settlement areas, and an even greater percentage of subsurface resources.

The Crown and aboriginal peoples sign modern treaties with great fanfare. They give aboriginal peoples a sense of optimism and new beginnings by providing them with numerous tools, institutions and opportunities to design their own social and economic futures. These tools can help them leave behind an often appalling legacy of paternalism, broken economies, poverty and cultural breakdown.

Ironically though, successful implementation of these modern treaties and achievement of their attendant hopes and dreams requires the active engagement of the federal, provincial and territorial governments as partners. Modern treaties replace the paternalism of the 1876 Indian Act. Modern treaties do not set out the terms of a divorce; rather, they define the terms of a marriage. Each promise in a modern treaty confers a right protected under Canada’s constitution, so the Government of Canada cannot unilaterally alter these agreements. The marriages defined in modern treaties are permanent, as far as anything in the modern world can be so characterized. Too often though, for Canada modern treaties are “marriages of convenience” requiring only “bare bones” maintenance.

Implementing Modern Treaties

At the heart of the implementation challenge is the complexity, scope and detail of the agreements themselves, which provide much room for differences in interpretation of duties and obligations. Aboriginal peoples and the government have different decision-making cultures, yet have to work cooperatively day by day to achieve modern treaty objectives. Only small pools of qualified and experienced aboriginal people are available to take the jobs and make the decisions that transform paper promises into on-the-ground realities. Lack of training within aboriginal communities is a serious deficit. Couple that with funding shortfalls and inaction of the federal government and the provincial and territorial governments, and factor in the inherent conservatism of government agencies that are themselves often poorly coordinated, and it is not hard to see why there are implementation problems.

Successful marriages require shared commitment and ongoing effort by both partners. It really does take two to tango. But aboriginal signatories report that the Department of Justice takes a minimalist view of the government’s modern treaty obligations, and that various line departments including environment, fisheries and oceans, transport, and others are only peripherally engaged. Line departments seem happy to assume, incorrectly, that the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, a weak agency in the Ottawa pantheon, is wholly responsible for the government’s modern treaty obligations. AANDC, for its part, has been unable to ensure a “whole of government” approach to implementation. Deputy Minister Michael Werneck admitted as much to the Senate Committee on Aboriginal Affairs when, in 2008, he noted that AANDC could not compel federal agencies to implement modern treaties, notwithstanding their constitutional status. Ignorance of modern treaty obligations is, according to aboriginal organizations, the rule among federal agencies. As a result, many modern treaty “marriages” are more or less dysfunctional.

Convinced that many implementation problems were Ottawa-based, in 2003 all First Nation and Inuit modern treaty organizations established the Land Claims Agreements Coalition to press the Government of Canada to remain true to its commitments. Chaired by the Nisga’a Nation of British Columbia and Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., the Inuit organization charged with implementing the 1993 Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, the coalition suggested that an independent modern treaty audit and review body be established—essentially a marriage guidance counsel—to report regularly to Parliament. The coalition’s suggestion has been endorsed by the Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples and the auditor general of Canada.

The coalition also suggests that the federal Cabinet approve a formal policy to ensure all required departments of the federal government participate in implementing modern treaties. Notwithstanding ten years of effort by coalition members singly and collectively, the Government of Canada has yet to adopt this suggestion.

Looking to the Courts

There has been considerable jurisprudence in recent years interpreting aboriginal rights, but such has not been the case with modern treaty rights. This is perhaps unfortunate since decisions by judges are evidence-based, definitive and binding, and in the face of federal reluctance to fully embrace modern treaties this seems increasingly to be needed. But in December 2006 Nunavut Tunngavik submitted a statement of claim in the Nunavut Court of Justice alleging that the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement had been breached contractually 16 times by the government. Alleged breaches included social, economic, employment and environmental provisions, funding shortfalls, and withholding consent to 17 requests to arbitrate disputes. NTI claimed damages of $1 billion.

the Crown was indifferent to its obligations over many years and was only prodded into action by this lawsuit … I am satisfied that Canada’s failure to implement an important article of the land claims for over 15 years undermined the confidence of aboriginal people, and the Inuit in particular, in the important public value behind Canadian land claims agreements. That value is to reconcile aboriginal people and the Crown … It is also important … to ensure that the Crown properly respects and fulfills its obligations under land claims agreements.

In April 2014 the Nunavut Court of Appeal set aside the monetary damages awarded by the trial judge, but confirmed that Inuit are entitled to monetary damages that reflect money saved by government in failing to implement the monitoring provisions of the agreement. Monetary damages will now be calculated as part of NTI’s full court case scheduled for trial in March 2015. It seems possible, even likely, that this case will end up before the Supreme Court of Canada and establish benchmarks and tests for implementation of all modern treaties. Certainly Justice Johnson’s finding that the Government of Canada was “indifferent” to its monitoring obligations raises the question of whether indifference lies behind additional alleged breaches of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement and alleged breaches by the Crown of other modern treaties.

Getting Things on Track

It is important not to characterize difficulties implementing modern treaties as a recent phenomenon; governments of various political and ideological persuasions have contributed to the problem and failed to seriously consider policy and program solutions. Yet in 2004/05 the coalition met regularly with representatives of Prime Minister Paul Martin’s short-lived government to negotiate a modern treaty implementation policy. All this came to an abrupt halt with the election of Stephen Harper’s Conservatives in January 2006 and the almost immediate disbandment of the Cabinet Committee on Aboriginal Peoples and the Secretariat in the Privy Council Office that served it.

It may be that modern treaties are so complex that implementation will always fall short of the ideal, but a first step is surely for the government to recognize that there is a real problem and to work with aboriginal peoples to fix it. Unfortunately this cannot be said of John Duncan, Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development from 2010 to 2013, who on November 11, 2011, informed the House of Commons Standing Committee on Indian and Northern Affairs that “we’ve made enough serious progress over the last three years really that most of the [modern treaty implementation] issues have gone away. Our implementation has been done very well.”

In light of the conclusions of the auditor general, the Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples, the Nunavut Court of Justice and the Land Claims Agreements Coalition, this is a highly imaginative, even inventive, statement.

The coalition’s suggestions to improve implementation of modern treaties seem sensible and doable, particularly if the Cabinet Committee on Aboriginal Peoples was reconstituted to consider the matter. But altering the “machinery of government” to establish a modern treaty audit and review body requires the prime minister’s approval and authorization. This does not seem likely. Prime Minister Harper has never spoken about the place of modern or historic treaties in national affairs. In light of the fact that most modern treaties apply in Northern Canada, it is particularly disappointing that implementing them is ignored in the Government of Canada’s Northern Strategy, released in 2009.

Litigation is perhaps a partial alternative to the proposals by the coalition, but is time consuming, expensive, of uncertain result, polarizing and destructive of relationships. Moreover, litigation focuses attention on alleged past mistakes rather than on doing things better now and in the future. But in the absence of any sustained willingness by the government to address shortcomings in implementing modern treaties, it seems likely that more disputes will be litigated.

Failure to live up to treaties is already generating public protest. Winter 2012/13 witnessed protests by aboriginal people across the country under the banner of Idle No More. Directed toward their own leadership as well as the federal government and provincial and territorial authorities, the protests demanded implementation of treaties, both historic and modern. The media pigeonholed Neil Young’s 2013/14 cross-Canada odyssey as a protest against increased development of Alberta’s tar sands, but that is not the only way it was billed by Neil Young himself and the Athabaskan peoples with whom he cooperated. To them it was a tour to “Honour the Treaties,” an angle to the story all but ignored by the media.

Aboriginal peoples are effectively on their own when it comes to pressing the government to fully and properly implement modern treaties. With the exception of a relatively small cadre of academics (particularly anthropologists, lawyers, geographers and historians) who churn out case studies of public policy decision making, aboriginal peoples have few to turn to for support. Civil society, including environmental and public interest organizations, are almost wholly ignorant of modern treaties. The 2012 Nunavut Land Claims Agreement summary judgement on environmental monitoring was not even commented upon by national environmental organizations, yet Inuit were standing up for the principle of environmental monitoring in more than 20 percent of the country.

Hundreds of charitable foundations provide financial and intellectual support to numerous organizations and causes including hospitals, environmental conservation, food banks, poverty relief, education and research, and so on. Remarkably little support is provided to Canada’s aboriginal peoples. Lack of understanding or support from civil society is mirrored in the rare coverage of modern or historic treaties by national newspapers, television and other media. That the recommendations of the 1996 Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples received such short shrift from the media and civil society as well as from the government suggests that this has long been the case.

With the obvious exception of aboriginal peoples themselves, there is no constituency in Canada pressing politicians to honour, implement and live up to the obligations in modern treaties. The Government of Canada feels little need to engage on the issue so the sensible proposals by the Land Claims Agreements Coalition languish. Can anything be done to change this situation? Can implementation of historic as well as modern treaties be brought into the mainstream of Canadian politics and debate? We are not sanguine. While firmly committed to the rights of individuals the current government, reflecting its Reform Party roots, is lukewarm at best to collective rights exemplified by modern treaties. Be that as it may, we offer the following thoughts:

There is no substitute for political leadership. The prime minister is hugely powerful in our political system, so if serious change is to occur, Stephen Harper, or his successor, will have to signal his personal commitment to full, complete and generous implementation of modern treaties and re-establish the Cabinet Committee on Aboriginal Peoples to pursue this goal.

The Cabinet should approve a formal policy to implement modern treaties, signalling to every agency and department the commitment to a “whole of government” approach.

It is largely as a result of court decisions in the last 40 years that several aboriginal peoples have regained some of their land and rights previously lost. Now is the time for Parliament—the seat of our democracy—to take up the grand cause of aboriginal treaties in public hearings across the country. To quote Saskatchewan-based academic J.R. Miller, the light of day needs to be shone on these “compacts, contracts and covenants.”

Most Canadians know very little about aboriginal peoples, and what they learn from the media suggests that aboriginal problems are “insoluble.” This stereotype must be challenged by aboriginal peoples “talking with Canadians” and explaining to them that implementing treaties is part of the answer to many of their social and economic problems. Aboriginal leaders should commit to educating the Canadian public and opinion leaders that fully implementing treaties is a route to the future not an excursion to the past. To develop such a communications strategy will require much thought and long-term commitment and will necessitate aboriginal peoples to cooperate closely among themselves. The proposed national parliamentary hearings would be a start.

In 2007 Adrienne Clarkson, then governor general, said “we are all treaty people.” She is correct. All Canadians, whether born here or not, have a stake in seeing modern treaties—the law of the land—fully implemented.

Terry Fenge is an Ottawa-based consultant. He was research director and senior negotiator for the Tungavik Federation of Nunavut, the Inuit organization that negotiated the 1993 Nunavut Land Claims Agreement.

Tony Penikett was the 2013 Fulbright Arctic Scholar at the Senator Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington. He is the author of Reconciliation: First Nations Treaty Making (Douglas and McIntyre, 2006).