In the not-too-distant future, you will have a driverless car that accepts voice commands for your destination. You will get in the car and read your news and messages on a device (probably a wearable one) that is connected to all of your other devices and machines, including your car, your home and office computers, your television, and likely your refrigerator and home thermostat, too.

All of these machines and devices will be intelligent, like your car, and connected to the internet. They will accept voice commands, link to your other devices and, based on your habits, routines and personal preferences, they will predict (hopefully with some degree of accuracy) what you need, what you want and when.

Copyright law may seem removed from this future, yet as technology has advanced over the past 15 years or so, so has copyright law. Copyright can affect our access to networks and the many computerized machines we use on a daily basis, and it is why the public will increasingly care about this formerly dry, industrial subject. The more people care, the more they will affect digital copyright’s development.

Copyright policy around the world is high on the agenda for critics such as Cory Doctorow and Blayne Haggart. They are the authors of new books about copyright in the digital age, how it is changing, who is driving the change and what it means for artists, governments and consumers.

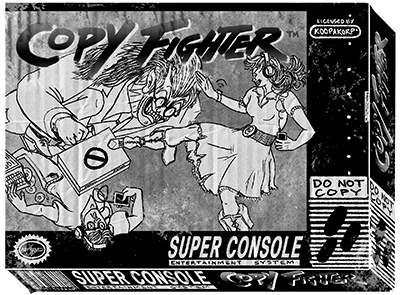

Tyler Klein Longmire

Doctorow’s book, Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free: Laws for the Internet Age, is part manifesto, part instructional guide, part digital copyright critique, for artists trying to succeed in and understand the new and evolving digital environment.

The book wears a title that plays on the “Information wants to be free” slogan attributed to 1960s counterculture writer Stewart Brand, who was referring to the way technology radically reduces the cost of disseminating information. Doctorow, a Canadian-born science fiction author, copyright activist and co-owner of the Boing Boing blog, says it is time to stop talking about information wanting to be free, and start talking about people wanting to be free. “That’s what this book is about. What people want from computers and the Internet. What we stand to gain, and what we stand to lose,” he writes.

Haggart, a professor specializing in international relations and political economy at Brock University, has penned Copyfight: The Global Politics of Digital Copyright Reform, an academic study of the implementation of copyright treaties by Canada, the United States and Mexico. ((I should disclose here that Haggart generously cites me in his acknowledgements for being his “first guide into the weird, wonderful world of Canadian copyright policy,” partly because of my master’s thesis.)) He traces these countries’ legislative implementations of two treaties of the World Intellectual Property Organization, and finds that, international as this policy is, and even as the United States uses its international heft to try to lever copyright law changes onto other countries, small countries such as Canada and Mexico can still wield influence and shape their own copyright policy destinies.

Why is everyone so concerned about digital copyright? One of the most controversial areas of copyright policy today is anti-circumvention law, or legal remedies against breaking digital locks (in copyright parlance, these are called technological protection measures, or TPMs).

These are programs that prevent copying, and often block or control access to gadgets, devices, video games, programs, digital content and computer systems. It is due to these kinds of programs that you cannot share or “lend” your Kindle e-book to someone indefinitely, or drop a copy of Photoshop onto an external hard drive to give to a friend. Digital locks prevent you from doing that. And they are getting more sophisticated. “When you sold someone a book, back in the day, they got the whole thing in one package,” Doctorow writes. “With digital locks, you can sell them only the right to look at the book after 6 p.m., while physically located in North America and not in a commercial establishment. If they want the ‘read on the subway’ rights, those can be sold separately.”

He jests, of course, yet Doctorow is saying that, in theory, we could use digital locks to make an e-book fail to work on the subway, and sell consumers separate subway rights for the access. We already sell separate book rights for digital and print, and separate rights for downloaded movies versus streaming movies, even though both downloads and streams technically make copies. There are digital locks on content to prevent people from using it in different countries around the world, as has been the case with DVDs.

Technically, the locks are not necessarily a large obstacle for consumers. In fact, it usually is easy to break them. Almost as fast as digital locks are made, hackers can respond with an unlocking program that people can install to break a lock. In the view of Doctorow, Haggart and many others in the “copyfight,” this would not be such a big problem if users were permitted to break digital locks.

But they are not, according to copyright laws around the world that have been updated over the past decade or so. Regions that make it copyright infringement to circumvent digital locks include Canada, the United States, the European Union and several other jurisdictions. It is an issue because, as Haggart says, “TPMs effectively transfer control over a work from the purchaser of a work to whoever put the lock on the work.”

If you cannot break the lock, you cannot regain control, and it is not just control of works that we are talking about here. It is control of machines and devices, or as Doctorow writes, everything from smart hearing aids to driverless cars: “You and I and most of the people we know will spend a large chunk of our lives with computers inside our bodies. We will also spend much of the rest of our lives inside of computers, some of them moving at very high speeds.”

Anti-circumvention law has largely spread on the backs of the WIPO’s two internet treaties of 1996, which required contracting countries to provide “adequate legal protection and effective legal remedies” against breaking digital locks. The treaties took some time to be implemented, but their creation, spearheaded by the United States, cleared a path for many of the laws we have today around the world.

Perhaps the second most controversial copyright law to gather momentum in the past 10 to 15 years is one mostly arising from the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 in the United States, which set out the terms of copyright liability for network “intermediaries.” These include your typical internet service providers such as Rogers or Bell, search engines such as Google or Yahoo!, and other internet platforms such as Facebook. If these companies are mere third parties on the internet, delivering you connectivity, networking platforms, and search functionality, how much should they be responsible for what people share on their networks, especially infringing stuff?

A range of legal remedies have emerged to address this question, some of them provoking bigger public responses than others. The U.S. through its Digital Millennium Copyright Act and the EU through its Electric Commerce Directive of 2000 set up “notice-and-takedown” regimes within copyright law. Under this system, the internet company takes down the content after receiving an allegation that the content is infringing and has been posted without authorization.

Most jurisdictions around the world have adopted either this notice-and-takedown approach, or a more moderate version called “notice and notice.” Under this system, the internet company, rather than removing the material, gives notice to its poster that there has been a complaint that the material is infringing. The poster of the content typically takes it down, and, if not, could face court action.

Haggart notes that, since 2007, “more extreme approaches” have been adopted due to “political pressure from the content industries seeking to offload enforcement costs onto ISPs.” These include France’s HADOPI law, which initially involved a “three strikes and you’re out” approach in which users accused of unauthorized downloading could be cut off from internet access. The French government, in July 2013, amended the system to one of graduated fines, acknowledging that a three-strike system and cutting off internet access was “totally inappropriate punishment.”

In the U.S., the country’s largest ISPs, including AT&T, Cablevision, Time Warner Cable, Verizon and Comcast, have voluntarily created a “copyright alert system.” Also known as the “six strikes” system, the providers alert their internet subscribers when their accounts are being used for copyright infringement and unauthorized file-sharing. After repeated notices, ISPs’ options for action include throttling the user’s bandwidth or, worse, redirecting them to a “landing page for a set period of time, until a subscriber contacts the ISP or until the subscriber completes an online copyright education program,” according to the U.S. Centre for Copyright Information, a website of major copyright owners.

With the rise of the internet, devices and mobile communications, copyright policy has been increasingly confronted by an inherent, fundamental paradox. As Bruce Doern and Markus Sharaput write in Canadian Intellectual Property: The Politics of Innovating Institutions and Interests, copyright law struggles with the oppositional, dual roles of fostering “dissemination” and ensuring “protection.” “In practice, all copyright laws express a particular balance between these two roles: providing sufficient protection to encourage production while limiting their damage to dissemination,” Haggart writes.

Striking this balance, in the past, was largely a process that did not involve the public. Copyright laws did not touch the end user. Publishers negotiated copyright with writers, and users bought books. Recording companies signed contracts with musicians (usually taking ownership of their copyrighted songs), and users bought records and CDs. The studios made movies, negotiated soundtracks for them, and users bought movie tickets, or DVDs. The copyright bargain was largely an industrial one between companies and creators.

Technology has broken the bargain. End users have rather suddenly come face to face with copyright. It is affecting their use of the internet, their ability to use software the way they want, program computers the way they want, manipulate content the way they want. This is not a question of the way things should be for the content industries, or the way things should be for artists; it is a question of the way things are for consumers and end users. If they want to use technology to copy, not much is going to stop it. Drop a boulder into a creek and the water will find a way around it.

Haggart calls this public involvement “the new politics of copyright” that will characterize the “global digital copyfight.” He says, “The involvement of individual citizens in what was previously a commercial law negotiated among large corporate actors has the potential to change the entire complexion of copyright law.”

This was the case in early 2012, when public involvement reached new levels after the U.S. Congress proposed the Stop Online Piracy Act in the House of Representatives and the Protect IP Act in the Senate. The bills would have effectively blocked Americans’ access to forbidden websites identified on special lists. Wikipedia, in protest, “blacked out” its website for 24 hours and encouraged visitors to contact their legislative representatives about the bills.

The following month, in February 2012, protestors in about 200 European cities held street demonstrations against the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement, a multinational treaty on intellectual property rights enforcement. As a result of public responses in the U.S. and Europe, Congress backed away from SOPA and PIPA, and the European Parliament rejected ACTA.

For all of these two books’ discussions on how copyright has changed and the forces behind its evolution, neither talks in detail about the differences between the laws in place and the ways they are being enforced. It is an important distinction as some of the biggest copyright-owning companies out there, including major software companies, recording companies or movie studios, have backed away from targeting consumers for activities such as unauthorized file-sharing.

People are not getting sued for unlocking their cellphones or cracking the TPMs on their Kindles or Apple TVs. In fact, people are unlocking these devices and using them as they want. Meanwhile, the big studios are concentrating their efforts on copyright infringement “enablers” such as Pirate Bay or websites offering pirated streaming video.

If the past few years are a guide, the future of technology holds that the trend toward unlocking or “jailbreaking” your devices will rise. As people wear more tech, use more automated, predictive gadgets and machines, rely more on fast, neutral networks and even start implanting technology into their bodies (hey, this is very real), they are going to demand more control than ever over their technology and networking. And they are going to be making lots of copies. “Computers are copying machines, as is the Internet,” Doctorow writes. To “read” or “load” a file is to copy it.

Doctorow’s book has chapters on how artists can succeed in a world where copyright may not apply, with tips such as how to use fame to your advantage, and how to make money selling merchandise and commissioned works, among other strategies. Supportive as it is for the copyfight, the book instructs readers why they should join that fight, but not how. Is it just a matter of changing one’s opinion? Perhaps Copyfighter is his next book. Or, maybe the public is already there.

Simon Doyle is the executive editor of Online News Services at Hill Times Publishing Inc. in Ottawa.