Every animal needs to eat, but no human being can, as the Old Testament has it, live on bread alone. We require more than mere calories. We require narrative, meaning, significance. What we eat (not to mention when, where and with whom) is more than fuel for persisting as an organism—it is foundational to who we are.

And who are we, then? According to Lenore Newman, Canada Research Chair in food security and professor of geography at the University of the Fraser Valley, we Canadians are—wait for it—people who learned to eat in a manner that makes it a little less horrible to live in a place where it is cold pretty much all of the time. In Speaking in Cod Tongues: A Canadian Culinary Journey, Newman travels across the country to examine how this vast land and its history have influenced our national relationship to the rituals of the meal. Her research leads her to advance a tentative notion of a Canadian cuisine, primarily as a food culture built from “wild food, seasonal food, and multicultural aspects of our society.”

“Cuisine” is a loaded concept, a piece of nationalist mythmaking and a means of drawing boundaries and borders across our plates. Newman borrows her defining terms from noted French 18th-century gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (“food is all those substances which, submitted to the action of the stomach, can be assimilated or changed into life”), and from Columbia University sociologist Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson (“cuisine is the formal and symbolic ordering of culinary practice”).

But she never quite makes the case that these terms can be stretched across a country as new or broad as ours. Opening with a consideration of the lavish meals served aboard the Queen Victoria at the Charlottetown Conference of 1864, drawing on founding father (and early foodie) George Brown’s diaries of the diplomatic mission toward confederation, Newman describes how their trip up the St. Lawrence river “seemed to be more like a culinary cruise than a serious round of nation building.” The anecdote is charming, but considering that the foods served then were prepared according to French culinary methods, and the best meals to be had in Canada today range wildly from top-notch Filipino restaurants in Toronto, Greek-Turk–inspired donair kebab in Halifax and innovative luxury sushi experiences in Vancouver, it’s hard to square this nice bit of myth with a relationship to a living and proud tradition of specifically Canadian cooking.

Josh Holinaty

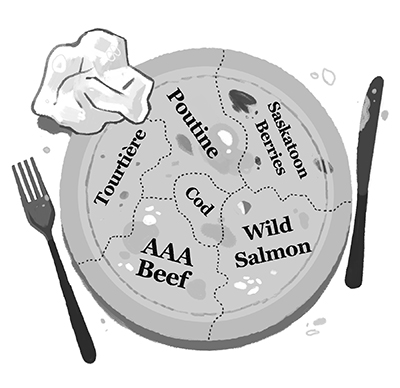

Newman details her adventures eating her way from coast to coast: wild salmon in Vancouver, heartland Saskatoon berries and Québécois tourtière, and the titular cod tongues (which are, if you are a stickler for anatomy, actually the tender little muscle from the jowl area of the fish’s neck) on Fogo Island. Newman’s culinary tour seems to leave few regional delicacies unsampled. The middle section of the book tackles regionality in three chapters, “Quebec and Ontario,” “Alberta and British Columbia” and “The East Coast, the Prairies and the North”—a sort of “East, West, The Rest” approach that underscores the absurd futility of comparing regions so geographically and sociologically diverse as these. The generous reading would be that Newman has arranged her analysis by population density, but the final of these chapters especially betrays the perfunctoriness of the project’s scope. Electing to write here primarily about commercial dining experiences rather than home-cooked meals, she ends up favouring regions with large urban centres with robust dining scenes that plainly offer more to write about (and to eat!).

Examining the idea of cuisine primarily through regional dishes in professional kitchens makes a certain kind of sense—restaurants being one conduit for culture, especially in cities. And yet it feels like a missed opportunity. Newman’s academic research elsewhere examines the pressures that rapid urbanization put on Canadian farmlands. While she hints at this work in Cod Tongues, describing Canada as a country with “one of the lowest rural populations percentages in the developed world,” the book barely touches on how Canadian farming and fishing are changing, or worse, disappearing, because of rural population decline.

Similarly, Newman sustains only a shallow discussion of the exclusionary practice of asserting a Canadian cuisine throughout, referring to the ways that First Nations food cultures have seldom received larger recognition in the country’s culinary imagination and, yes, citing the multicultural and multi-ethnic make up of our general population. Still, it seems as though these observations take on the role of mere quibbles; the base question of why we must endeavour in the nationalist work of articulating a specifically cross-country Canadian cuisine is seldom really engaged with in the text.

Allow me to ask it here, then. Why must there be a Canadian cuisine? Newman refers throughout Cod Tongues to the ways in which the food we eat has been shaped by French and British colonialism, regionalism, increased urbanism, the rise of California cuisine and, naturally, our country’s farms and foodways. Due to the multiple and sustained catastrophic effects of colonial settlement on the First Nations of this land, our knowledge of pre-settlement cuisines, including First Nations agricultural practices and indigenous crops and plants, is incredibly limited. Newman mentions pemmican, a sort of old-school protein bar made of powdered bison meat and grease with a shelf life of five years and a whopping 3,500 calories per pound, as one known and recorded element of a pre-colonial–contact cuisine of the Cree nations in the prairies, but it must be said that the food and gustatory cultures of indigenous groups do not easily fall under the banner of Canadian cuisine—it is simply not our right as settlers to outright claim the historical traditions of First Nations, even as many sites of indigenous agricultural cultivation and foraging have shaped regional and contemporary diets among both settler and aboriginal populations.

The regional diversity of Canadian diets and food cultures is well represented, but rather than bolstering her argument for a nationalist project describing the rituals of how and what we like to eat, Newman’s snacking tour of Canada undermines the notion of a nationally coherent meal. Much more invigorating would be taking Newman’s account of the ways in which Canada’s foodscape is ethnically and geographically diverse, a creole of cooking styles, wild ingredients and hyper local specialties that adds up to something other than niceties and nationalist dream making. Examining the specific and idiosyncratic elements of local food cultures and economies leads to a more nuanced and urgent understanding not only of the intersecting systems of policy and culture in preserving local food sources, but also, in the case of Cod Tongues, to more interesting and evocative prose.

In fact, Newman’s writing is at its most enlightening and persuasive when her knack for storytelling—and her deeply researched nods toward the geographic specificities of food security and production—reveal the importance of understanding the diversity and idiosyncrasies in our country’s foodways. In detailing the remarkable recent history of poutine’s rise from humble beginnings to stand in the international imagination as a prototypically Canadian dish, or in her nuanced portrait of how Alberta’s political economy ties directly into the province’s reputation for Triple A beef, Newman’s writing is at its most provocative and significant when the somewhat ham-fisted idea of a truly national and unified cuisine recedes. Her accounting of the devastating overfishing of Atlantic cod in mid 20th century is affecting and revealing, and Newman blends the known and reported facts with a dining tour of present-day Newfoundland that works to underscore how the earlier political folly of allowing unrestricted cod fishing backfired in a community where the basic act of eating is often underscored by loss. By honouring the regional distinctiveness of the conditions she is describing, Newman is able to attain a level of nuance that is lacking in the conception of the larger project of forcing as much as possible into a single nationalist pot.

Emily M. Keeler is the vice-president of PEN Canada. Her writing has appeared in the Guardian, Globe and Mail, The Walrus, and Toronto Life.