On the topic of social media, Richard Seymour, the Marxist blogger and author of Corbyn: The Strange Rebirth of Radical Politics, knows whereof he writes. Like so many others, he has been chewed up in its electronic maw — in his case, for a couple of comments he incautiously made on Facebook in 2015. As he ruefully noted a year later, after the shitstorm erupted, “The potential audience for anything posted on the internet, is the entire internet, plus the audience of any print or broadcast media that takes it up.”

Seymour has been reading, thinking, and writing about social media for a while now, an interest possibly precipitated by that experience. He describes his new book, published in Europe but not yet in North America, as a “horror story.” Its germs can be found in his popular but now abandoned blog, Lenin’s Tomb, specifically with such pieces as “We Are All Trolls,” from December 2016, and the last post he wrote there, over two years ago, “On Fetish.”

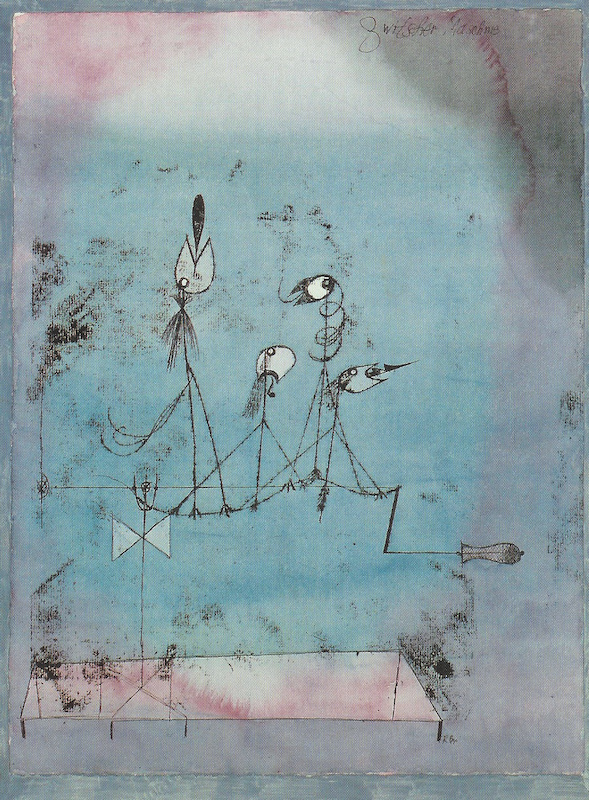

Twittering Machine, by the artist Paul Klee, offered him a fortuitous metaphor for his subject. The 1922 work depicts singing mechanical birds luring unsuspecting victims into a pit. Just so, Seymour argues, social media beckons us, and once we fall into its virtual pit, we find ourselves digging deeper. And we labour, often for hours a day, at the task.

The young Karl Marx wrote about this kind of trap. “The more the worker spends himself,” he said, “the more powerful becomes the alien world of objects which he creates over and against himself, the poorer he himself — his inner world — becomes, the less belongs to him as his own.” Later, in Capital, Marx observed, “Machinery is put to a wrong use, with the object of transforming the workman, from his very childhood, into a part of a detail-machine.” When it comes to the internet, these are prescient words.

Our scripturient state of being.

Detail of Paul Klee’s Twittering Machine (1922) / Wikimedia Commons

Our modern Twittering Machine — that is, the sum of Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, YouTube, and other commercial platforms, including, of course, Twitter — acts in just such a fashion upon us. (While Google is not, strictly speaking, a social medium, we can add it to the list. It sucks up and processes user data to the same ends.) But there are important differences: Workers sell their labour power to live. Those who sit before the screens of the Twittering Machine and manipulate its keys are giving their labour away freely.

Yet “freely” is a dangerously misleading word. When we are trapped, even voluntarily, we cease to be free. Smokers are not free when they reach for a cigarette: they are, after all, addicted. And we become literally addicted to social media, through deliberate and manipulative techniques of stimulation, generated by algorithms that we ourselves help to refine each time we pick up our phones.

As never before in history, we have become “scripturient”: anxiously, feverishly, and incessantly writing for hours on end. We tweet, we text, we update our statuses while scrolling, swiping, tapping, clicking, hovering, and linking. By so doing, we — billions of us — generate a vast amount of data. Seymour emphasizes the scale:

By 2017, users had shared more than half a million photos on Snapchat, sent almost half a million tweets, made over half a million comments on Facebook and watched over four million YouTube videos every minute of every day. In the same year, Google was processing 3.5 billion searches per day.

These ubiquitous commercial platforms put the data we generate minute by minute to profitable use. Our likes and dislikes, our politics, values, interests, and preferences are recorded, sorted, and used to separate us into demographic subsegments, each ripe for increasingly tailored advertising. Put a different way, as a necessary component of the always-evolving Twittering Machine, our buttons become more and more easily pushed, and to greater and greater effect.

There is nothing very new in any of this. The virtual reality specialist Jaron Lanier made many of the same observations just last year in Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now. Lanier called the Twittering Machine the BUMMER machine, for “Behaviors of Users Modified, and Made into an Empire for Rent.” And back in 2011, the internet activist Eli Pariser covered some of the same ground in The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You. Seymour has primarily provided us with a digest of the burgeoning literature addressing the dangers of being online.

The Twittering Machine acts like a laboratory’s Skinner Box: a stimulus-response chamber with a system of rewards and punishments that keep us, like Skinner’s pigeons, coming back for more. Our “free-floating attention [is] guided down channels strewn with reinforcements that we often don’t even notice.” We are “denizens, not citizens” of this new contrived realm, and we make it ever more monstrous with our returning presence.

Many of us are hooked to an alarming degree, thanks in good part to the smartphone. In 2015, the developer Kevin Holesh designed an app that tracked daily usage: he found that 88 percent of smartphone users spent a quarter of their waking lives on their phones. Using Holesh’s app, the addiction psychologist Adam Alter (the author of Irresistible: The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked) discovered, to his amazement, that he was spending three hours a day on his own phone. Other research indicates that the average user performs “2,617 touches, taps or swipes” daily, and 10 percent of smartphone users check their phones during sex!

In Canada, the numbers seem more moderate but are still a matter of concern. A Forum Research poll in 2018 found that 28 percent of us use our smartphones for two or more hours daily, but for young people (between eighteen and thirty-four) the figure was 50 percent. The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission reports that there were 31.7 million mobile phone subscribers in 2017 — out of a population of 37 million. According to the Canadian Internet Registration Authority, 57 percent of us engaged with social media last year.

“Addiction is all about attention,” and the Twittering Machine is above all an attention economy. “Time on device” is the goal of the enterprise, as it is in casinos. The “intermittent variable rewards” are the addictive lure — delivered in no small part by the “like” button. When Facebook added that simple pleasure stimulus in 2009, subscriptions ballooned, and other platforms followed suit. (Facebook now offers a range of buttons, to draw us in and calibrate our responses to an even greater extent.)

Social media does not directly compel any particular point of view: that would discourage users and hence affect corporate profits, which are staggeringly large. Platforms exercise a minimum of editorial control over content. Community standards, for example, are a joke. There is no “community” as such, and any “standards” invoked are unequally applied, their implementation frequently skewed by “report troll” campaigns.

Yet in order to recreate user “highs,” and hence “time on device,” their algorithms — preciously secured, as Lanier notes, and up to this point never hacked or stolen — inevitably propel us toward the dramatic, the sensational, the extreme. Earlier this decade, ISIS won recruits and support through its skillful use of the Twittering Machine. The alt-right, too, flourishes in this environment.

Indeed, Seymour worries at some length about the fascist potential of the machine, although his analysis can be confusing at times. For example, he claims that the link between sociopathic trolling and right-wing politics isn’t clear, but in the next breath he notes that these trolls

are overwhelmingly white men from anglophone and Nordic countries, who disproportionately attack women, queer and transgender people, black people and the poor. Their vaunted detachment performs a familiar white-male fantasy of ironclad superiority.

To a greater or lesser degree, “we are all trolls.” As Lanier puts it, “Social media is making you into an asshole.” There is something about this virtual environment that generates bad behaviour, that makes us twitchy, irritable, pointlessly combative. The Twittering Machine, as Seymour knows first-hand, can be a nasty place.

Our dark side tends to emerge when the consequences to ourselves are so slight and the investment of time and energy so little. The machine is a playground of ungoverned id impulses. Usually cloaked in anonymity, we bully, we troll, we “call out,” we lie. But the machine can quickly and without warning turn on us, and that can have major real-world consequences.

As Pariser noted eight years ago, echo chambers (or, as he called them, filter bubbles) have been a feature of social media for some time. The “general audience” has ceased to exist, replaced by content algorithmically chosen for individual users, including Google searches. But this process can be endlessly refined: so if trolling, bullying, and harassment turn off too many users, the corporate social media can turn down the heat by adjusting the algorithm.

The long-term cultural effects of the Twittering Machine are likely profound, but, as Seymour points out, we’re at far too early a stage to be certain what those effects might be. Six hundred years ago, Gutenberg’s printing press led to the Reformation, the modern nation-state (Benedict Anderson’s “imagined communities”), and the Industrial Revolution. It also deeply affected the way individuals look at the world. But who could have predicted any of that in 1450? “The spontaneous assumption might instead have been that the Catholic Church would be empowered,” Seymour writes. “The first mass market created by print was in standardized indulgences.”

Marshall McLuhan is barely mentioned in the book, but it’s worth recalling his views on print, as well as his gloomy prescience about new media. “This is the Age of Anxiety for the reason of the electric implosion that compels commitment and participation, quite regardless of any ‘point of view,’ ” he wrote in 1964. He was talking only about radio and television in Understanding Media; imagine what he’d make of the Twittering Machine.

Seymour, too, is deeply pessimistic. What if we all just quit, as Lanier and others advocate? Seymour considers this a reactionary position, which offers no real way forward because it doesn’t address the social malaise that makes us seek the addiction in the first place. Seymour’s own horror story, as he puts it, “is only possible in a society that is busily producing horrors.” Hence, if we were to kill off the existing machine, “the media, amusement and entertainment complexes would fuse with venture capital to do it all again only more efficiently.”

We do need “a theory of how to get out before it’s too late” — what Seymour terms an “escapology.” But what then? He offers only a few unconvincing suggestions for overcoming our agitated scripturience. Fall into reverie? Take a walk in the park, with notebook and pen in hand? Hardly serious alternatives. Perhaps it is already too late.

John Baglow reads and writes in Ottawa.