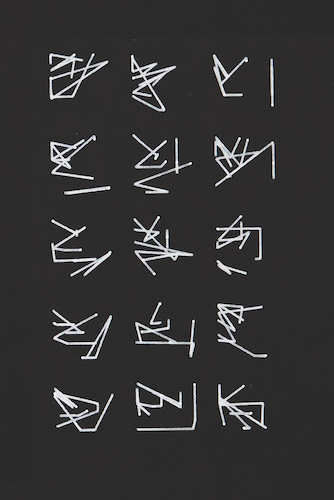

Written language sleeps when we do: the areas of our brain that process it go dormant. Any text we experience in dreams is asemic — with no actual semantic content. Made of meaningless symbols, it might present an image of readability, perhaps beguile us with a reading-like experience, but it never comes together like a true linguistic text.

Dreams aren’t the only places we find texts like these. In Asemic: The Art of Writing, Peter Schwenger delves into the ways we perceive and receive marks that look like language and feel like language but are, emphatically, not language. Focused on artists who have used asemic writing in their work, from the 1920s through the 2000s, he explores “writing that does not attempt to communicate any message other than its own nature as writing.” While asemic texts may not present “a coherent message,” they do indeed reflect “a coherent sign system.”

Considering asemic texts can feel a little like staring into the void, especially with marks that feel almost familiar. The painter and sculptor Cy Twombly, for example, made swooping gestures that recall the cursive exercises from his childhood in Virginia. Assembled in lines, their repeating loops make the viewer’s fingers twitch in recognition. They echo a relationship with language anchored in a physical experience that leaves out what we normally think of as reading — bringing us back to a time when the world of writing was obscure, before we had learned to translate our thoughts into intelligible marks.

The Chinese artists Wenda Gu and Xu Bing build character systems out of ancient seal script (Gu) and orthographic rules (Xu Bing). In his first solo exhibition, in 1986, Gu used calligraphic gestures to create massive imagined characters so close to real language that the authorities shut him down, convinced the symbols were hiding something, a subversive message just waiting to be translated. Xu Bing’s monumental works, meanwhile, offer their would-be readers whole volumes filled with asemic texts that follow, character for character, the modes of Chinese script. Gu’s and Xu Bing’s works disappear if you don’t know their operating rules, reappearing only through comparison with a meaningful text. By looking like language, they give the illusion of translatability but resist it, confound it, all the while reinforcing the rules that govern the systems they’re based on.

A beguiling reading-like experience.

Golan Levin; Flickr

Western artists have often used Chinese characters as models for their own asemic projects, their illiteracy allowing them to cultivate a language-like experience that ignores the referent language structure, replacing it with an exoticized fiction. Gu and Xu Bing turn these misreadings and appropriations on their head, with a series of encounters that produce alienation on all sides. In the installation China Monument: Temple of Heaven, for example, Gu mixes pseudo-languages to make a statement about misunderstanding, what the artist calls “the essence of our knowledge concerning the universe and material world.” It’s almost like the high-art equivalent of a pop star’s misguided tattoo.

The relationship between asemic reading and translation taps into what the theorist Emily Apter has described elsewhere as a mythology of untranslatability. She traces it back to religious texts and looks at how even non-readers can use written language to relate to the divine. For believers, words are often sacred, and even when they are fixed in a tactile codex — as they are in book-based religions like Judaism, Christianity, and Islam — full translation of meaning remains impossible. Always somewhat impenetrable, the unchanging source retains its connection to something more than human. Readers and believers have to meet that text on its own terms.

The true power of the untranslatable text comes with an inscrutability that excludes the uninitiated, with a shroud of secrecy. For Apter, the “mystery” can go hand in hand with “the paranoia-inducing closure of foreign language-worlds.” We start to imagine the meaning of words we don’t understand; fear can creep into and warp that untranslated space.

Translation maps out war zones — as well as trade routes and shared communities — and while Schwenger and his artists never venture too far into political territory, their creative output begins to suggest ways around or portals through those paranoid spaces. Rather than “using language, that valuable tool of the colonizing impulse, to translate the natural world into human terms,” eco-asemic art “reminds us that natural objects may have a voice of their own.” The Canadian artist angela rawlings, for one, is concerned with texts that will never be translated; there’s no message, per se, hidden in her ecological interventions, just as there isn’t one waiting to be decoded in Gu’s asemic characters. In both cases, readers have to find a different way of interacting with what they see — a way that frees them of the paranoia Apter describes and gets them closer to a different kind of interpretation.

What emerges in Schwenger’s book is an aesthetics of language, and of reading in particular, that draws attention to how asemic writing lets us dive into the untapped possibilities of incomprehension. Is it so easy to escape the pitfalls of language? All our dreams are asemic, but that doesn’t make them all utopian. What sets asemic works apart from other forms of writing, Schwenger argues, is that, by replacing translation with a kind of hallucination, they make us attentive to how quick we are to find frustration or freedom when we encounter the world without the support of familiar signs and assumptions.

Schwenger ends his book by discussing some Amazon reviews of Michael Jacobson’s asemic novella The Giant’s Fence, from 2005. One of them reads, “As a literary traditionalist in many ways, I must confess that I had a high level of skepticism when opening The Giant’s Fence.” But even for that traditionalist, the asemic work opened up: “Once I could let down my critical guard . . . the images began to adopt semantic meaning and gain symbolism. I found a primitive language emerging from what the symbols began to form for me.” The reader recounts a distinctive experience that Schwenger’s Asemic ultimately explains: Reading without meaning is a meditative act. If we give up the power of decoding and accept the limitations of our understanding, mere symbols are transformed into something bigger, and a dreamlike experience can point us toward the unknown.

Ruth Jones is one of the magazine’s contributing editors.