It being Wednesday morning, I’m set to lecture on Don DeLillo. And I’m in a child’s playroom. This room, you see, is the quietest in the small apartment that my partner, Anna, and I recently rented from another professor, who’s on sabbatical. My plan is to explore with my students some ethical quandaries in recent American literature. I did not plan for the colourful posters: a pistol-brandishing, red-bearded pirate is hovering over my left shoulder; a prancing chimpanzee is hovering over my right. Surrounding each, and lending an air of spookiness, are purple and orange Halloween decorations.

I recall the Simpsons episode in which Homer, under repeated questioning, admits that he did not in fact spend his evening discussing Wittgenstein over a game of backgammon but instead spent it eating mustard packets in Barney’s car. Suddenly forced to teach from home, it’s harder to hide the mustard-packet sadness of real life from my students. I shrug and turn on the camera to begin my first online lecture, finding myself without the self-restraint to resist cracking the weak and obvious joke: “Before we start, let me address the elephant in the room — namely, the novelty-sized stuffed elephant to my left.” (Hey, it got some laugh emoji in the student comment thread.)

As COVID-19 brings life to a standstill, many have described the disorientation of seeing their city’s realities transformed. However, for Anna and me, even everyday life in Tel Aviv, where we arrived six months ago, is disorienting. Neither of us is Jewish, nor do we speak anything more than tourist-guide Hebrew. Tel Aviv’s atmosphere of orchestrated chaos seems utterly unlike life in the cities — Vancouver, Toronto, Edmonton, Ottawa, Kingston — we know best. Even something as simple as shopping, which for me involves squinting at packaging as though this will somehow make it more readable, can induce despair. As much as we love Tel Aviv’s liveliness, grittiness, and warmth, for us, normality here remains tinged with strangeness.

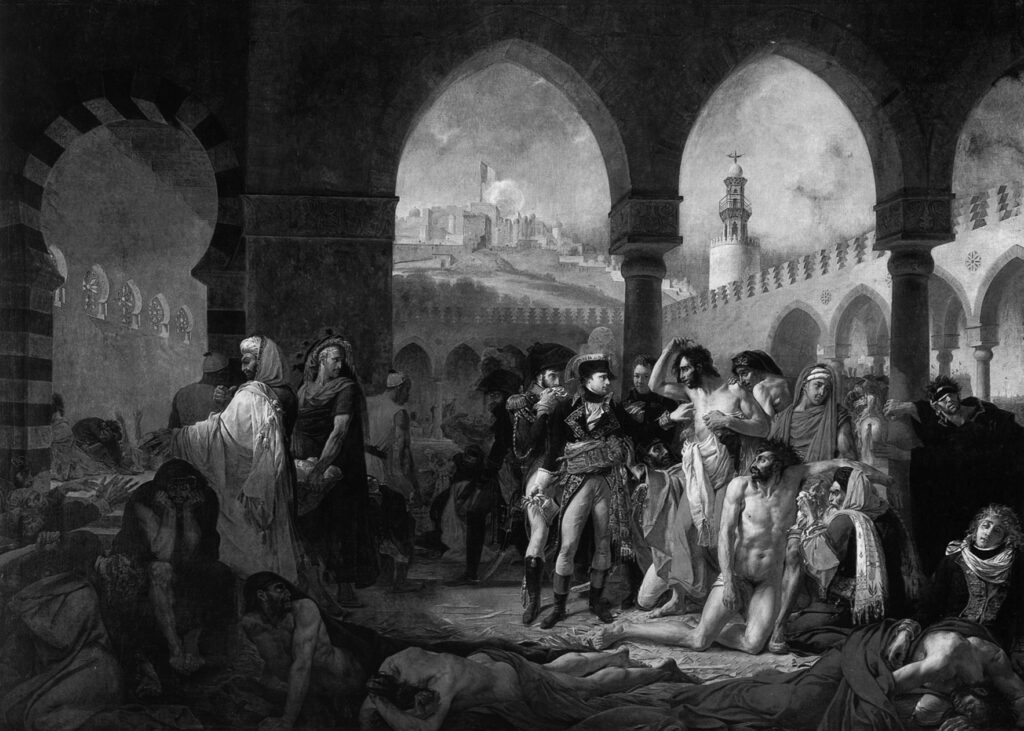

Between past plagues and ours.

Antoine-Jean Gros, Bonaparte Visiting the Pesthouse in Jaffa, 1804; Wikimedia Commons

Undeniably, though, the present crisis gives this strangeness new dimensions. Packed with bars and cafés, our neighbourhood, Nachalat Binyamin, is among the trendier nightlife spots in what is known as the Middle East’s hedonistic party city. Now its sidewalks are largely desolate and its stores shuttered. The buildings that line these streets — heritage Bauhaus numbers, crumbling bunker-like apartments, sleek condos and high-tech offices — seem newly eerie in the absence of people, their graffiti more colourful. Walking around feels especially disorienting, because Israel’s ever-changing health edicts are issued in Hebrew; we aren’t always sure what is and is not permitted. (Are we even allowed to walk? If so, how far and for what purpose?) We try to keep abreast of changes by reading the English edition of Haaretz, but suspect we’re missing vital information.

In fact, most of our pandemic-related news still comes from Canada. Like everyone, we’ve read endless stories about the virus, losing ourselves in the numbers and the predictions, our minds numbed by info‑whelm, our nerves frayed by uncertainty over when and how life will return to normal, and by fear for friends and family. That these stories come largely from the CBC, the Globe and Mail, Maclean’s, and The Tyee produces an inescapable mental disconnect. Walking through Nachalat Binyamin, I acknowledge the virus’s invisible presence and see the tangible effects of Israel’s response to it. Yet the narratives through which I process these phenomena reference life an ocean away. So far, my experience of the coronavirus involves awkwardly grafting Canadian narratives upon a Tel Avivian reality.

At Nachalat Binyamin’s heart lies the city’s largest outdoor market, Shuk Hacarmel. Typically packed with vendors of spices, meats, fish, fruits, and cheap knick-knacks, its grid of laneways sits empty, red and white lettering dangling from a rope above its entrance: “Don’t Panic.” To be honest, I’m not sure Tel Avivians ever needed the reminder. Many appear entirely at ease. I’ve read North American journalists’ commentary on Israel’s pandemic response — among the swiftest and severest anywhere. They emphasize the citizenry’s unusual readiness for sudden restrictions on daily life, a reflex bred by the region’s unending wars. Yet rather than martial self-discipline, most Tel Avivians seem possessed of a cavalier indifference in the face of threat.

About three weeks after moving here, Anna and I were awakened by air raid sirens for the first time. Dutifully, we rushed to our building’s safety zone, as instructed. We felt standard greenhorn embarrassment upon discovering that almost no one else had even bothered to leave their apartment. On the rare occasions when air raid sirens sound, I’ve since been told, most people laugh, shrug, and blithely continue with their day. Likewise, until stricter rules were recently imposed, Tel Aviv’s beachfront promenade remained thronged with pedestrians. This might remind you of, say, Vancouver’s gallingly crowded seawall, but here the heedlessness is, for better or worse, a habit, part of history.

When it was still permitted, I would rise early and run along the beach before the throngs arrived. My route goes south to Jaffa, Tel Aviv’s predominantly Arab quarter. I would pass the port — possibly the world’s oldest, and the site from which Jonah, the prophet of God’s wrath, is believed to have sailed before being swallowed by the whale — reaching a path at its southern edge that curves along a ridge above the Mediterranean. Along this route lies Saint Nicholas Monastery. There, in 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte is said to have visited French troops who had contracted bubonic plague while conquering Jaffa. (A portrait of the visit, commissioned by Napoleon himself in 1804, hangs in the Louvre.)

I think of the time between that plague and ours, of the many distances — closed borders, restricted travel, home isolation — that shape today’s pandemic. I think, too, of how the phrase “social distancing,” commonly defined as the physical separation of people, inadvertently evokes something else: namely, the growing ethos of individualism and waning commitment to public, common, social goods that have left the country directly to Canada’s south so ill equipped to respond to COVID-19. And then I think of what Napoleon supposedly once said: “Nothing is more difficult, and therefore more precious, than to be able to decide.”

I wish I didn’t have to teach from my rented children’s playroom again tomorrow, but now, it seems, the virus is the one deciding everything for us, even in this land of checkpoints and security walls. Here, as in so many places, it can be difficult to remember that we’re all in this together.

Spencer Morrison is a professor of American literature at the University of Tel Aviv.