Week three of the Bay Area’s “shelter in place” order, and still the occasional plane thrums overhead, its landing gear tilted toward SFO. My toddler will hear it first, soft cervine ears attuned to any small shift in sound. He signs for “airplane” with a swoop of his hand, and I wonder about all the empty seats up there, a ghost flight swooping in to find a region gone strangely quiet.

For those of us now painting blood over our door jambs and staying inside, this feels like a moment of suspended reality. As my partner began working at our bedroom desk in mid-March, switching her university courses to online learning, I had an ear on the news, nervous. The Grand Princess cruise ship was approaching San Francisco Bay with nearly two dozen positive COVID-19 cases and another 3,500 guests and crew needing quarantine. So I did a Target run and filled the trunk with groceries, just in case. The contagion is now everywhere but, at least for now, still elsewhere — a palpable horror in the hospitals, apparently, although in this apartment of ours, it’s mostly encountered through the Johns Hopkins online dashboard. What makes this disaster so experientially strange is that we’ve been told, essentially, not to extend a hand. That we can best help by just staying put — flatten the curve! — which means my life is more or less as it was: reader, writer, stay-at-home father.

When the public library closed its doors for the foreseeable future, I turned, for the first time in a while, to my “to be read” shelf and pulled out Rebecca Solnit’s The Encyclopedia of Trouble and Spaciousness, her collection from 2014. In twenty-nine essays and dispatches, she visits, among other places, Fukushima, Japan, after the tsunami; Tunisia during the Arab Spring; Iceland before and after the 2008 financial crash; and Silicon Valley in the age of technological privatization. Solnit writes with an infectious mix of hope and critique; hers is a voice that consistently offers wise and politically astute antidotes to despair.

I kept going after I finished the book, rereading two others I had at home: the slim Hope in the Dark, which Solnit wrote during the Iraq War, and A Paradise Built in Hell, which I had first read a few years ago while preparing a writing course on disasters and climate change.

Help for navigating a disrupted world.

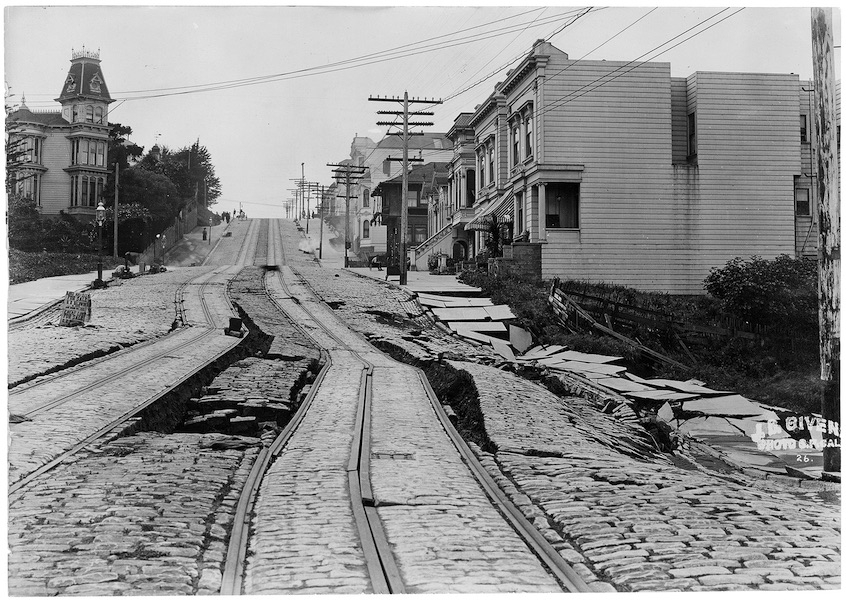

U.S. National Archives

In Paradise, Solnit writes of surprising collective responses to disaster, including the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, the 1917 Halifax Explosion, the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, New York after 9/11, and post-Katrina New Orleans. Throughout, she documents the many ways in which people —“not all, but the great preponderance”— step up when ordinary life is shattered. Surfacing from her interviews and archival research is the recurring, almost embarrassed admission of a certain enjoyment that many feel in the aftermath. “We don’t even have a language for this emotion, in which the wonderful comes wrapped in the terrible, joy in sorrow, courage in fear,” she writes. “We cannot welcome disaster, but we can value the responses, both practical and psychological.”

Paradise is now ten years old, but readers continue to turn to it amid subsequent disasters (including the election of Donald Trump) for its historical guidance and for courage, maybe even solace. And it has functioned as an empowering counterweight to “disaster capitalism”— the relentless efforts to wrench yet more power and wealth from the social upheaval caused by catastrophe that is the subject of Naomi Klein’s 2007 book, The Shock Doctrine. The scramble for power, Solnit writes, may be one consequence of calamity, but the end result is not a foregone conclusion: “Disaster is sometimes a door back into paradise, the paradise at least in which we are who we hope to be, do the work we desire, and are each our sister’s and brother’s keeper.”

During disasters, contrary to conventional belief and Hollywood plot lines, we do not generally stampede one another, becoming immediately hysterical and selfish, pillaging and fighting. Neither do we grow glassy-eyed and utterly helpless en masse. Solnit reminds us that after the levees failed in New Orleans, people responded with extraordinary altruism (remember the ad hoc Cajun Navy). The secondary disaster that followed the hurricane and flooding was the official response of the police, government officials, and the media who imagined victims as enemies, as perpetrators of mass rapes, and as murderers — all fears that later proved unfounded. Many of those who died of abandonment, or trying to cross the Danzinger Bridge, were “demonized and dehumanized.” Beliefs matter, she keeps repeating, and the stories we tell about each other give shape to our public and private acts. In a world that’s increasingly hit by natural and social catastrophes, “knowing how people behave in disasters is fundamental to knowing how to prepare for them.”

It may be too early in this pandemic, when we’ve been forced indoors rather than into the streets, to know how our collective responses will fully play out. But as things look from my window and laptop screen, it seems unlikely to disprove Paradise’s thesis. Consider our widespread cooperation with municipal, state, and provincial requests to “shelter in place” and practise “social distancing”; we came to a massive economic and cultural consensus over that in just a few days. And those spring breakers, Mardi Gras revellers, and St. Paddy’s Day drunks have now been shamed and seem, mere weeks later, like participants in the last stupid hurrah of a more innocent time. There’s been a run on toilet paper, sure, but that hardly reflects mass panic; as North Americans, the bottomless consumers of the world, we’re simply not used to seeing the back of the shelf.

A few days ago, I knocked on our elderly neighbours’ kitchen window and confirmed that their son had left them groceries. Yesterday, another neighbour passed a jug of milk and a bottle of Motrin through our door, giving us an extra week without having to make another grocery run. My Mennonite church, in a nineteenth-century throwback, has started up a “mutual aid committee” to triage human needs and available resources. As Solnit writes in Paradise, “In the suspension of the usual order and the failure of most systems, we are free to live and act another way.” Those of us unskilled in the medical professions and deemed “non-essential” are relearning how to connect with and care for each other in old and innovative ways, while the emphatic heroes of the moment don personal protective equipment and venture daily into the epicentres of crisis.

Solnit has become a consistent quarantine presence, and not only for her writing on hope, disaster, and social change. A few days ago, another invaluable front-line worker, the courier, dropped Recollections of My Nonexistence on my doorstep. This latest book of Solnit’s further underscores her prophetic voice. About Solnit’s formative years in 1980s San Francisco, it is a welcome set piece in her prolific oeuvre. And since I’m new to this city and state (and still relatively new to this country), I’ve been eager to read my way into this place — all the more so now that I can’t get out on foot.

Over the past fifteen years, Solnit’s non-fiction has grown increasingly direct and emphatic. She has explored the politics and social underpinnings of her world view in memoir and travel writing and in essays that have truly changed the way we see North American culture. Her 2014 feminist collection, Men Explain Things to Me, for example, grew out of a viral essay of the same name and helped give shape to the now-pervasive idea of “mansplaining” as a species of misogyny. Then she turned out three other collections in as many years: The Mother of All Questions in 2017, Call Them by Their True Names in 2018, and Whose Story Is This?: Old Conflicts, New Chapters in 2019.

Solnit takes us back to the vibrant scenes of late Beat poetry and punk, of queer and activist countercultures during the AIDS crisis, and of Western Addition, her neighbourhood in San Francisco, which grew out of the Second Great Migration of African Americans. Hers is a view of the city when silicon chips were still actually made nearby, before that “waterfall of acceleration we would all tumble over.” She explores her own writerly maturation by reflecting on the various “nonexistences” that defined her “almost friendless” late teens and twenties — when she was a GED kid and transfer student at San Francisco State University. She describes her early books and essays as “milestones or shed snakeskins” and says that “underneath the task of writing a particular piece is the general one of making a self who can make the work you are meant to make.”

Recollections opens with three essays that narrow by a factor of ten, moving fluidly from the Bay Area’s duplicate mirrors of sky and water in “Looking Glass House,” down through the vanishing world to the unexpected gift of Solnit’s long-time apartment in “Foghorn and Gospel,” through to a dowel-legged Victorian desk in “Life during Wartime”— the same desk on which she has written her millions of words. It’s that third essay that marks a decisive and stunning shift. She describes how the desk came to her from a friend who, a year earlier, had survived being stabbed fifteen times by an ex-boyfriend. “Someone tried to silence her,” Solnit remarks. “Then she gave me a platform for my voice.” The legacy, the weight of Solnit’s desk is felt through the collection, as she writes on its surface about living under the threat of violence and street harassment, of having an epiphany in the SFMoMA archives, of navigating the white patriarchal world of publishing. These constitutive experiences helped shape her life’s work as a maker and breaker of stories.

Solnit repeatedly returns to the epidemic of violence against women — a disaster long unseen and unspoken. “Violence against bodies,” she writes, has been “made possible on an epic epidemic scale by violence against voices.” In writing of her survival and of finding her own voice in the middle of that fight, she does not see her path as one for others to follow, scorning the idea that “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” Rather, hers is a lament for and a warning against the many costs — in body, in spirit, and in silences not yet named — of pervasive violence.

As memoirs go, Recollections is not dripping in tell‑all detail. That said, Solnit includes a colourful anecdote of herself and a friend sporting bright chiffon dresses and crashing one of William Burroughs’s sombre, denim-and-leather boys’ club birthday parties. Someone photographed the three of them, with Burroughs looking “like a slug between two saltshakers.” And she names some other names, taking both City Lights co-founder Lawrence Ferlinghetti (her first publisher) and Artforum co-founder John Coplans (who tried to destroy that first book) to task for contributing to her early sense of invisibility.

Not all of her youthful feelings of non-existence were negative, however. During those years, she lived alone in books, finding herself “faceless, everyone, anyone, unbounded, elsewhere, free of meetings.” More than “an escape,” reading brought her into contact with the prose experimentation of Milan Kundera and Jorge Luis Borges and the mixing of the personal and political, as well as voices and styles that shook up the supposed objectivity her journalism program at UC Berkeley espoused.

Which is precisely what astonished me when I first came across Solnit’s writing: an evocative style that braids strands of memoir and research with a seemingly effortless attention to environment and aesthetics. I’m trying, amid the pandemic, to not lose every hour to the barrage of anxious news. I’m holding on, in other words, to the reading and writing strategies that I’ve honed while caring for this baby, one whose increasingly dexterous hands now swipe at my book and claw at my keyboard. Like quarantined parents the world over, I’m trying to “do work” without also neglecting my child, so I’ve taken to leaving Solnit’s books open in different rooms, stealing five- or ten-minute bursts of prose while leaning on door frames, peripherally aware of the toddler diving in and out of his “hot tub,” our cheap pleather ottoman. Occasionally, I offer a public reading to an audience of one, arresting his attention with sentences that extend, meander, and roll off the tongue with a vivid lyricism (blight removal of the 1950s and ’60s, for example, left “open wounds in the city’s skin of structures”) or stunning metaphor (“A book: a bird that is also a brick”).

Even in better times, when not locked indoors, San Francisco has become a hard nut to crack. Our rent is not so much a slice of the pie as it is the entire dish. And shortly after we moved here last year, wildfires cast a grey haze of particulate into the atmosphere, while electricity in nearby counties was pre-emptively shut off during windstorms. We huddled indoors for a few days; this spring, we’re doing the same for different reasons, and for much longer.

If this pandemic is a window on our collective, precarious futures, I’m happy at least to have Solnit continuing to tell us stories about ourselves so that we might better understand who we are, collectively, and how we might live and love differently. In turn, I’m sensing this place and its people beginning to crack open, neighbourly small talk now tipping into genuine care. We’re getting ready, in other words, to survive together.

Inspirations

Wild Possibilities

Nation Books, 2004

Penguin Books, 2010

Trinity University Press, 2014

Viking, 2020

Geoff Martin was nominated for a Pushcart Prize for “Baked Clay,” an essay about Mennonite and Black land histories in rural Ontario.