On September 5, 1914, George Herman Ruth Jr. hit the first home run of his career, at Hanlan’s Point Stadium. On the Toronto Islands that day, in a large concrete and steel ballpark, the nineteen-year-old pitched the first game of an International League doubleheader for the Providence Grays against the local Maple Leafs. Memorably described as a “youthful southside phenom” by the Toronto Daily Star, he gave up one hit, walked three batters, struck out seven, and smashed a thunderous three-run dinger over the fence in the sixth inning against Leafs pitcher Ellis Johnson.

It would turn out to be the only minor-league home run for the man we remember as Babe Ruth. The whereabouts of the ball that would make fans and collectors salivate (and a lucky auction house quite happy) remains a mystery. Legend holds that it was stolen, or that it resides in a bronzed state in an unnamed restaurant, or that it rests in a watery grave. Today, two nondescript plaques at Hanlan’s Point are all that physically remains of the stadium and the deep fly that helped launch a career.

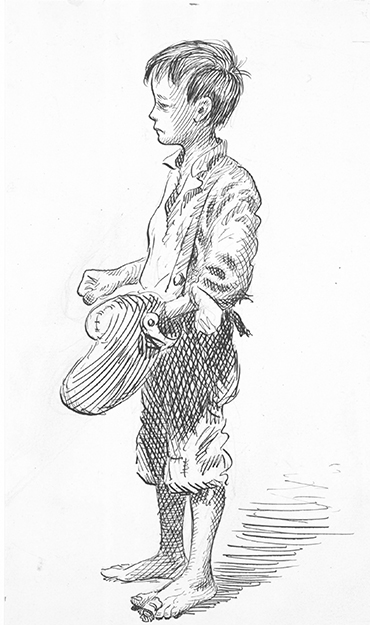

The little rascal who turned into a king.

An Embryo of a Baseball Star; A. G. Spalding Baseball Collection; New York Public Library

The slugger, also affectionately known as the Bambino and the Sultan of Swat, would return to Toronto in the 1930s, this time as a New York Yankee, in town to play an exhibition game against the same minor-league team in the same stadium. True to form, he hit another towering homer, which reportedly landed in Lake Ontario and was never retrieved. As Tom Valcke, former president and CEO of the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, once told the writer Jerry Amernic, “It would almost make draining the lake worthwhile if two of the Babe’s biggest taters are sitting on the bottom.”

Ruth’s connection to Canada is much deeper than the fate of two long-lost four-baggers, however. His fans of yesteryear, and admirers thereafter, owe a debt of gratitude to the kind heart and firm hand of a Catholic brother from Nova Scotia who intensely loved the great game.

Brian Martin’s The Man Who Made Babe Ruth brings to life the inspirational figure who helped transform young George into a sports legend. An educator at St. Mary’s School, in Baltimore, Brother Matthias played an important role that’s been discussed only lightly by others, including by Ruth in his 1948 autobiography. Martin, a retired London Free Press journalist and author of several books on America’s favourite pastime, has admirably lifted the veil much higher.

Brother Matthias was born Martin Leo Boutilier on July 11, 1872, in the small Nova Scotia community of Lingan, on Cape Breton Island. He was the eighth of ten children born to Joseph and Mary Ann Boutilier. His father, a Lutheran who converted to his wife’s Roman Catholic faith, was one of many men who worked in the local coal mines. But, according to Martin, “Joseph’s descendants believe he became overly zealous in his new faith and had some sort of religious argument at the mine that may have contributed to his departure.”

This helps explain why the Boutiliers left Nova Scotia in 1880, as does an extended period of financial hardship that afflicted the Maritimes. After briefly considering Halifax, the Boutiliers sailed to Boston, where Joseph found work as a machinist, while his older children settled into good jobs. They all became proud American residents. Martin was only nine when the family arrived in an East Boston neighbourhood that was “firmly in the grip of baseball fever.”

Different variations of the game, including round-ball, were played by young Bostonians, while the older players of the Boston Red Stockings were part of America’s first professional baseball league, the National Association. When the league collapsed, a separate franchise, the Boston Red Caps, became a charter member of the “more businesslike” National League. The Boutiliers became enthusiastic fans of this strange new game. “Like other immigrants,” Martin writes, “they soon realized that following baseball helped them bond with their neighbors, old-timers and newcomers alike.”

Religion also played a critical role in young Martin’s life. Along with his brother Thomas, Martin was “more spiritually inclined” than most of his siblings —“to the delight of their father.” Around 1890, he joined a congregation of the Belgium-based, English-speaking Xaverian Brothers. Though the organization didn’t train would‑be priests, it served as a lay “religious community approved by the Catholic Church.” It still does: “Like priests, the Brothers vow to dedicate their lives to poverty, chastity and obedience.”

Eventually, Boutilier was assigned to St. Mary’s Industrial Training School, a Xaverian institution in Baltimore, and became a full member of the brotherhood on March 25, 1900. He took the name Brother Matthias. He taught courses and served in the “key post of school disciplinarian,” which made sense, since he had grown to six feet, six inches and had come to be called the Boss by the young boys. More important for fans, Brother Matthias became one of the school’s baseball coaches — in another city that was fascinated with the game. And this led to his fateful meeting with the future Bambino.

George Ruth was born in Baltimore on February 6, 1895. He grew up in a working-class neighbourhood near Carroll Park, where he could safely play outside. Six years later, George Sr. inexplicably left his lightning-rod business to his older brother, sold the family home, and opened up a saloon not far from Camden Yards, where the Orioles play today. This was a much tougher environment, and the family’s new living standards were at the “top of the lowest class.” The Ruths barely had time to take care of young George, and he began to associate with boys “who easily found mischief in the busy cobblestone streets near the rail yards” and were “constantly getting into trouble in a rough-and-tumble part of town.”

Ruth quickly became “known to the police” and was occasionally caught “for petty larceny and mischief and taken home.” Discipline from his father served little purpose. A family friend, the policeman Harry C. Birmingham, who thought George was a “little rascal,” may have been the person who suggested sending him to St. Mary’s. The young scamp attended for short periods starting in 1902; the school became a permanent fixture in his life two years later. He would reside there for the better part of a decade.

Ruth had the choice of learning various trades, and he settled on shirtmaking for St. Mary’s forty-four intramural teams. Originally, he didn’t have much of an affinity for the sport that would make him famous. Martin suggests the game he played “in the streets may have resembled baseball in its most crude form, far below the level at which the boys of St. Mary’s played it.” And even at that, he didn’t play very often.

While a number of brothers at St. Mary’s, including Alban, Herman, and Gilbert, would play supporting roles in Ruth’s budding love affair with baseball, it was Brother Matthias who was the lead actor. As the school disciplinarian, he kept the youngster on the straight and narrow — although Ruth wasn’t actually all that “prone to fisticuffs.” He grew into a good-natured and thoughtful talent, “interested in the well-being of the other boys . . . especially the less fortunate ones.”

Brother Matthias, who taught at St. Mary’s until 1931, saw things in Ruth that others didn’t: Martin suggests that Brother Matthias may have first noticed “what scientists later determined to be [Ruth’s] superior hand-eye coordination.” While Ruth preferred to be a catcher, Brother Matthias “ordered him to go in and pitch” one day after he started acting up. (Of course, it was on the mound that he was later noticed and offered a major-league contract.) And while Brother Matthias discouraged boys from using their left hand in the classroom, and forced Ruth to juggle his glove as a left-handed catcher, he didn’t press a particular handedness when it came to batting.

Ruth started to mimic Brother Matthias’s “unorthodox but effective” playing style. This included “taking small pigeon-toed steps rounding the bases” and swinging the bat “with a powerful uppercut.” These St. Mary’s trademarks remained with him throughout his professional career with the Boston Red Sox, New York Yankees, and Boston Braves.

But all of this begs a question: If Brother Matthias played such a crucial role in the making of Babe Ruth, why has he been kept in the shadows for so long?

Martin offers several possible explanations: Brother Matthias was a rather shy gentle giant. He barely spoke about his enduring friendship with Ruth, other than in a long-forgotten interview with Thomas Shehan, of the Boston Evening Transcript (Martin reprints the 1935 exchange in this book). Brother Matthias continued to encourage his former student after he left St. Mary’s, and the Colossus of Clout later bought him multiple Cadillacs, but their private correspondence wasn’t made public until long after their deaths in the 1940s.

Moreover, Brother Matthias didn’t stop the braggadocious Brother Gilbert from claiming to anyone who would listen that he was the Bambino’s guiding force. But for all the interviews and banquet speeches, Gilbert’s singular role was in recommending Ruth to Jack Dunn, owner of the International League’s Baltimore Orioles — the Babe’s first professional team.

Martin’s wonderful book has brought an important story to the surface. We may not know where Babe Ruth’s baseballs are in Lake Ontario, but we now know a great deal more about the unlikely Canadian hero who helped him become one of the greatest players the game has ever seen.

Michael Taube is a columnist for the National Post, Loonie Politics, and Troy Media. Previously, he was a speech writer for Prime Minister Stephen Harper.