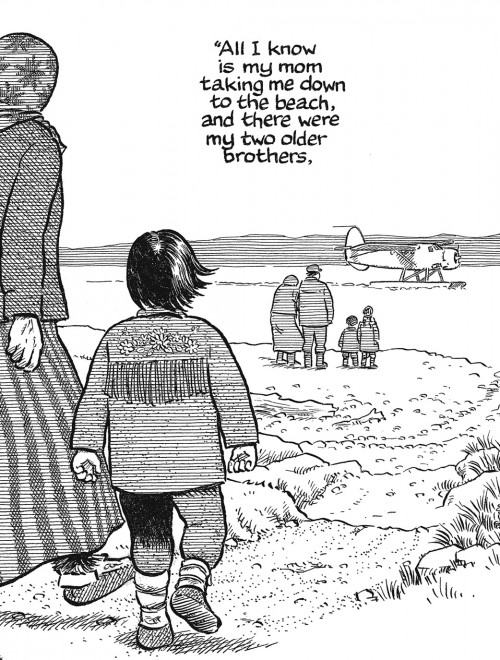

A squalling baby held aloft, its umbilical cord falling into a moose-skin boat beached on a riverside. Sinew nets bursting with fish. Dogs hauling laden sleds through the deep taiga forest. The fatty underside of a hide scraped with a flint rock. A cadre of kin working together to erect a camp along the Mackenzie River. These interweaving scenes, which open Paying the Land, come with a feeling of a history long since passed. But history is close at hand in the Northwest Territories — and the images are revealed to be a recreation of Paul Andrew’s childhood. Recalling his years spent living on the land, Andrew, a former chief of the Shúhtaot’ine, or Mountain Dene, describes a difficult but satisfying life, one “dictated by the environment, by the animals,” where youth, by watching, listening, and imitating their elders, found themselves woven into the circle of community and tradition.

Circles arise often in Paying the Land, as the cartoonist and journalist Joe Sacco winds the most complex story of his career into a finely tuned narrative loop. Sacco, who was born in Malta and now lives in Oregon, made his name while reporting in the Middle East (Palestine, from 1993; Footnotes in Gaza, from 2009) and the Balkans (Safe Area Goražde, from 2000). While this latest outing finds him in the far safer NWT, he comes to see it as a place that’s just as fractured as those war zones.

After contemplating the traders, missionaries, oilmen, and miners who have gone north of the sixtieth parallel to carve out their desired pound of flesh or soil, Sacco changes tack rather abruptly. He realizes there is something else at play here, some deeper, lingering problem that contaminates the earth beneath the Dene’s feet: if a circle has no beginning, where does one look to fix it once it’s broken?

Sacco seems aware of the snags an outsider like himself might catch upon in tackling a story like this: the white saviour complex, the noble-savage trope, the treaty-idolizing “John Locke that reposes in every Western heart.” And he knows its telling isn’t easy. Rather than finding media-starved people eager to share their past, Sacco encounters a culture that feels tired of talking and sick of not being heard. More than once, he’s told that those outside the bounds of family and community, especially those “poking around with their anthropology sticks . . . can fall into a more monetized sphere.” People are wary of his curiosity, and his medium isn’t always appreciated; one man makes it clear that issues facing the Dene’s existence are “not a cartoon . . . not a joke.” Such is Sacco’s compassion that the elusiveness he sees drives him only to indict himself.

“What’s the difference between me and an oil company?” Sacco asks. “We’ve both come here to extract something.” But, of course, there is a difference. He is measured without sounding distant, impassioned without being discouragingly biased. All the same, he largely recuses himself from the book; his presence as both narrator and character (drawn, as always, as a pulpy, blank-eyed caricature) is largely absent. This stance marks a departure from his other works, where he more fully integrates himself with the story through a sort of gonzo cartoonism.

Where history is close at hand.

Courtesy of Henry Holt & Co.

But intentional decolonization of the narrative leads the book to difficult places. Sacco does well to render the knot of economic and political dealings of the North understandable, a Herculean task considering the thousands of years’ worth of technological, religious, and societal change that descended upon the region in mere decades. Only midway through does the book begin to soar, as sparse white panels give way to a banking seaplane over a northern lake, the craft in transit to collect a payload of children bound for residential schools.

If Canada never openly declared itself to be at war with Indigenous peoples (as did the United States), it was only because war is predicated on a certain understanding of chaos. Ottawa’s method was anything but: blackmail, violence, and coordinated evacuations were used to fulfill the dreams of Duncan Campbell Scott, who, as deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs, promised “to continue until there [was] not a single Indian in Canada that [had] not been absorbed into the body politic.”

Flown to Inuvik’s Grollier Hall in the early 1960s, Paul Andrew was at the sharp end of that ambition. His language, family, and home were replaced with a number and a religion, as the process began of forcing this child — yet another nonentity from terra incognita — into the Anglo-Catholic mould. “You [weren’t] particularly anybody or anything. So they’re going to have to remake you,” he recalls. After the years of verbal, sexual, and physical abuse, “you begin to believe what they say, that you’re not good enough.”

Sacco has never shied away from putting the “graphic” in graphic novels, and anyone inclined to shrug off the horrors of residential schools and their consequences as overblown or rhetorical may find in his stark depictions of Andrew’s experience something more effective than cold understanding: empathy. We are visual beings, and reading a man’s description of his ordeals, while simultaneously watching the boy he was suffer through them, causes us to recoil. By chronicling individual after individual this way, Sacco reveals the impact the treaties and land deals had and continue to have.

Paying the Land is more than a collection of bad memories, however. There is also hope, although the term means different things to different people. While some Dene welcome resource extraction and a wage-based economy, others search for a clearer path back to the self-sufficiency of their ancestors.

The issues Sacco raises won’t be solved quickly, but there is an immediacy that runs through the work. Shared knowledge of language, legends, and bushcraft skills — all substantial facets of reclaiming Indigenous heritage — grows weaker by the day. Although there are no answers to be found here, it’s clear that in a world where the buck stops at capitalism, pain — especially the pain of the powerless — is often meaningless unless it can be coupled with an economic equivalent. Governments banking on ecclesiastical aphorisms (particularly “Money answers all things”) can repartee unto infinity; they will solve nothing so long as “How much did it hurt?” refers to the pocketbook and not the soul.

J. R. Patterson has contributed to The Atlantic and many other publications around the world.