My grandfather was among the forgotten Canadians of the Vietnam War, one of the hundreds of observers whom Ottawa sent to facilitate an all too elusive peace. Starting in August 1954, Canada contributed soldiers and civil servants to the International Commission for Supervision and Control, an unusual observer mission meant to facilitate France’s withdrawal from its former colony, monitor civilian and troop movements, and oversee an election to reunite a divided country. There would be no free and fair elections to unify Vietnam, though, and by the time my grandfather arrived in 1965, there was little peace to observe. He landed in Saigon not long after U.S. Marines came ashore at Da Nang.

Infighting among the Canadian, Indian, and Polish troops — each with different national interests at stake — left the commission paralyzed. Joint inspections and reporting were almost impossible; any criticisms were so diluted as to be without value. Canadians understood that their reports made their way to the Americans, and therefore to the South Vietnamese, just as Polish observations landed on the desks of their Communist allies. When the commission’s mobile teams could not reach the countryside independently, the Canadians sometimes joined American patrols — a practice that hardly indicated true neutrality. It was, my grandfather quickly realized, a complicated relationship.

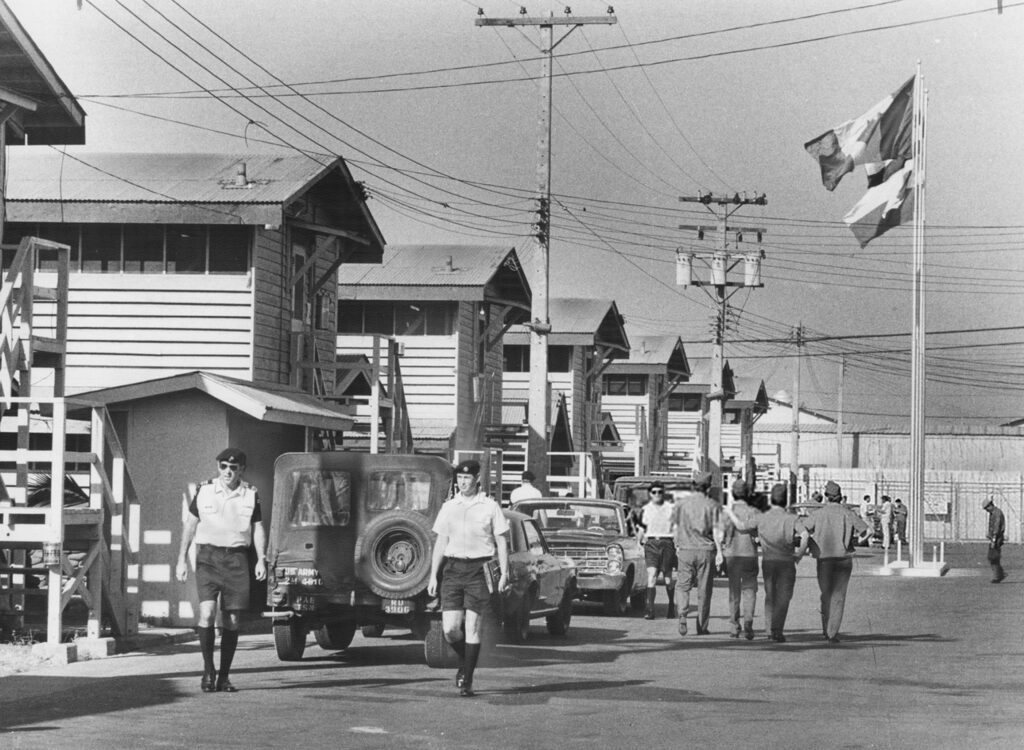

Postcards from an unusual mission.

Boris Spremo, 1972; Toronto STar

With The Devil’s Trick, John Boyko takes a hard look at that relationship. This is a story of a state divided against itself, whose leaders rarely took public positions and who muted their concerns enough to appease powerful allies. It is the story of communities that sheltered war resisters who fled north, even as other Canadians journeyed south to don American uniforms. And it is the story of an active protest movement that rallied against a conflict in which this country played no official part, even as our factories churned out weapons and chemical compounds destined for the Indochinese jungles. Canada was neither neutral nor belligerent nor opposed to the war. It was all of these things, yet none, at the same time.

My grandfather’s experience with the ICSC was much like Canada’s wartime experience in microcosm: well-intentioned, frustrating, constrained by Cold War realities. Both were mainly along for the ride. It’s fitting, then, that The Devil’s Trick is primarily a tale of a state and a people buffeted by events well beyond their control. It lacks a clear beginning, middle, and end, and it features no obvious heroes or villains. Boyko embraces his story’s complexity, and with engaging prose he focuses on those who navigated the maelstrom — cursed, like all of us, with their own circumstances, preconceived notions, and imperfect information.

As he did with Blood and Daring: How Canada Fought the American Civil War and Forged a Nation, from 2013, Boyko centres The Devil’s Trick on six flesh-and-blood characters. He begins with two diplomats: Sherwood Lett and Blair Seaborn. Both served as commissioners to the International Commission for Supervision and Control. Both tried to represent this country responsibly and in a way that might avert further war. Lett, the inaugural commissioner, put forth an admirable effort to fulfill the group’s mandate, but he lacked the carrots and sticks to do so. Things limped along, with Seaborn taking the helm in spring 1964. Seaborn had some successes in shuttle diplomacy, bringing messages from the American president to the North Vietnamese prime minister, Pham Van Dong, but whatever influence he may have had in steering the course of history vanished after the Gulf of Tonkin incident that August. No one was backing down, and the war was all but inevitable.

By opening with the two statesmen, Boyko illustrates the broader strategic context of the period and Canada’s place within it. Through Lett, he looks at the French withdrawal and the solidification of North Vietnam and South Vietnam. Through Seaborn, he explores the American road to the war, with which readers are likely most familiar and where Boyko spends much of his time. (While this approach works well, Boyko does not dwell on the Kennedy years. For that administration, readers can look to his 2016 book, Cold Fire: Kennedy’s Northern Front.)

With the strategic context explained, Boyko continues with four characters who are perhaps more relatable: an American war resister who came north; a leader in the Canadian peace movement; a Canadian who volunteered to fight in the U.S. Marine Corps; and, finally, a Vietnamese citizen who fled the regime with her family. Each provides a different perspective, and Boyko treats all of them respectfully and with care. He explores their personal motivations and shows us how they grew and changed with evolving circumstances and new information. This approach is most clearly on display with the case of Claire Culhane.

Culhane, remembered as a “One Woman Army,” went to South Vietnam as part of a medical mission. She initially found the humanitarian work rewarding but became disenchanted with the effort when she learned that her supervisor was providing patient information to the CIA. She was in South Vietnam during the 1968 Tet Offensive, returning home not long afterwards and becoming a vocal advocate against Canada’s complicity in the war. Through Culhane, Boyko looks at an active peace movement, the degree to which Canada’s defence industry benefitted from the war, and Pierre Trudeau’s policies and personal opinions. The prime minister opposed the conflict himself, but he felt constrained by the importance of Ottawa’s relationship with Washington. After Trudeau met with Culhane following a hunger strike, he whispered to her, “You have no idea the pressure I am under.”

Boyko then looks at the two-way street across the Canada-U.S. border: those going north to resist the fight and those going south to join it. Joe Erickson was one of 26,821 Americans who came to Canada to avoid the draft or otherwise resist the war, while Doug Carey, who was born in Connecticut but raised in Ontario, was among about 12,000 Canadians who served in an American uniform in Vietnam. In telling these two stories, Boyko does an outstanding job in analyzing their different motivations. Although their points of view seem diametrically opposed, Boyko does not paint one as right and the other as wrong; he lets their experiences tell the tale.

Boyko’s final character is perhaps the most moving. In 1978, Rebecca Trinh and her family fled their once comfortable Saigon neighbourhood amid government repression of the ethnic Chinese as Sino-Vietnamese relations worsened. Trinh’s story is gripping, full of danger and uncertainty. In one especially vivid scene, she must abandon a boat at night and swim to shore. She throws one child into the water to her waiting husband and then throws her baby into the air, jumps in herself, and swims up to catch the young child. To Boyko’s credit, he does not abandon his subject at the “happily ever after” stage of her resettlement. Indeed, while Canada opened its doors to 60,000 refugees in two years — an incredible achievement — Canadians did not universally support the effort. Plenty opposed the initiative, and new arrivals were not always well received.

“The devil’s trick,” Boyko writes in his introduction, “is convincing leaders that war is desirable, the rest of us that it’s acceptable, and combatants that everything they are doing and seeing is normal or, at least, necessary.” Those who are already familiar with how this trick played out for Canada and the Vietnam War will not find a great deal of original information in the new book. Lett and Culhane, for instance, have already been the subjects of full-length biographies, and Culhane wrote a memoir. Seaborn’s story is well-documented in Charles Taylor’s Snow Job and Victor Levant’s Quiet Complicity. Trinh’s tale is the subject of an editorialized “Heritage Minute.” But Boyko is to be commended for synthesizing a great deal of convoluted material into a single compact and highly digestible volume.

The Devil’s Trick is also remarkable in its balanced treatment of perhaps the most politicized conflict since the Second World War. Too many books on the Vietnam War are mere polemics, with just enough history to make them seem credible. Boyko’s telling, aided by his interviews with four of his six subjects, lets the characters help drive things through their own words and memories. Boyko asks his reader not to view the Vietnam War as just or unjust but to see that war is hell, with flawed human beings on all sides and caught in the middle.

Tyler Wentzell is a military and legal historian and Canadian infantry officer.