Morris Wolfe was an essayist, cultural critic, teacher, and editor, as well as a beloved mentor. He chose a medically assisted death on November 27, 2021. The writer Jules Lewis read this letter to him over their last lunch together.

Last night, I dreamt that I attended Morris’s funeral. The funeral, for some reason, was held at a YMCA. I sat in the back row, feeling very uncomfortable. There were fifty or so people seated in front of me in folding chairs; I didn’t know any of them. From the podium, a short old man with a cane blabbed on and on about how great and kind Morris was, about how sorely he would be missed. Nothing about the ceremony felt right. It was too formal. Too dour. And who were all these people in attendance? I wasn’t aware that Morris had this many friends — let alone friends who were still alive. In the back row, I began to feel queasy, bloated; it was as if there was some kind of fleshy basketball lodged in my stomach. I had to get out of there. Quietly, I slipped out the back door and headed downstairs to the change room. Here I sat on a bench, surrounded by white tiles and lockers, relieved to have escaped the grating atmosphere of the service but still feeling very ill. And this was where the dream ended. Perhaps it was telling me something significant about Morris’s death — about how it will change me, or about how it is something I am not yet able to digest. Or perhaps, as Morris would probably say, it was just a dream. Regardless, I’ll spare you any further analysis.

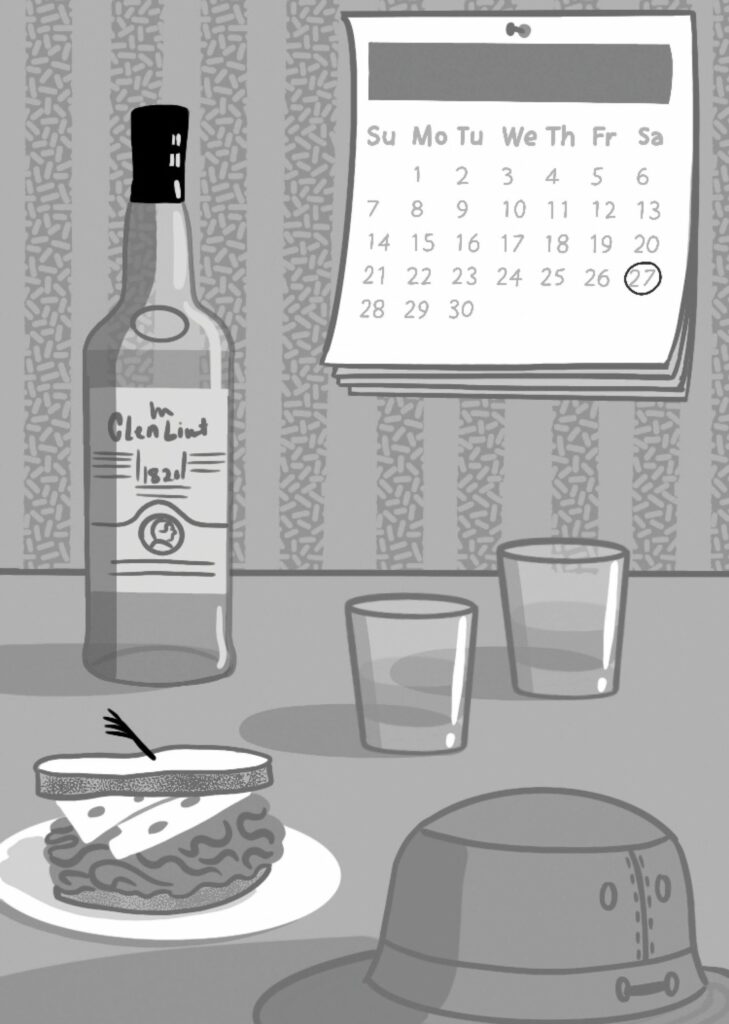

As I write these words, I picture myself reading them to Morris on a printed-out piece of paper over the last lunch we will ever share together. For the occasion, I will bring two corned beef deli orders — one with mustard (for me) and one without (for Morris). Oddly, about a month before, Morris had refrained from putting mustard on our weekly sandwiches, sliced from the dependable roll of Chicago 58 All Beef Salami in his fridge. I’m not sure why; he hasn’t explained it to me.

On this last lunch, to wash my sandwich down, Morris will offer me Scotch, a twelve-year-old Glenlivet, and encourage me to keep refilling my glass. Maybe I’ll begin reading this after I’ve finished the first half of my sandwich, I don’t know; but when I start, from across his living room table, Morris will hunch his neck forward and squeeze his eyes shut, to concentrate better. I will not look up from the piece of paper in my hands, hoping early on to elicit a chuckle. If Morris laughs, I’ll know I have done something right, written words with at least a modicum of truth or authenticity; if he remains silent, I can’t be sure. And if there is too long a silence, I may glance up from my sheet of paper, just to check that he is not grimacing. It occurs to me that so much of our time together has resembled this very interaction: me waiting anxiously to hear what Morris thinks about something I’ve written.

With Scotch and sandwiches.

Jamie Bennett

The first time I showed Morris a piece of my writing was when I was seventeen years old, on the second floor of the Starbucks at Runnymede and Bloor, in Toronto. We’d met through a friend of my parents; I was interested in writing, and she suggested that Morris might be willing to look at some of my work. For whatever reason, this established journalist, editor, and critic agreed to give me — some kid he’d never met and knew nothing about — the time of day.

I pushed my journal across the table, opened to its most recent entry: a messy handwritten passage about how I’d gotten the shit kicked out of me a few days earlier in front of an arcade in Koreatown. I sat there silently, terrified, while this bearded, sixty-five-year-old stranger, with a Tilley cap and a leather vest over his button-down shirt, tried to decipher my scrawl. Finally, Morris looked up from my journal. “Is this true?” he asked. I nodded and showed him my missing front tooth. There was a long silence in which I braced for the worst. “It’s good,” he said, then gently pushed my notebook back to me.

Those two words —“It’s good”— gave me enough confidence to show him another piece the following week. Since then, for over nineteen years, a month has not passed without us exchanging at least an email; and maybe only once or twice — while I was living outside of the city — have two months passed without us meeting in person.

Looking back, I don’t know what compelled me to trust Morris that afternoon at Starbucks with something so raw and so personal, but I did. It was a trust that over the years allowed me to share with him so much writing, so many things I couldn’t or didn’t know how to say. Maybe he saw in me that need to share. I came to see in him somebody who also contained much that was difficult or impossible to express — somebody who needed the intimate space that writing and reading provides. Another thing about this trust: over the years, it solidified out of a sense of knowing that Morris would not lie to me about my work. His responses were never extensive; often he just said, “It’s good,” or “It works,” or “This isn’t working,” or, sometimes, “My bullshit meter is going off here.” I had to read between the lines and decipher his intuition through what I imagined it might be. I never felt that he was leading me on or appeasing me. In fact, I can’t recall a time when my bullshit meter went off in response to anything he wrote or said to me. Then again, my meter is likely still in a nascent state of development.

Again, as I write this, my imagination returns to our last lunch together. Have we finished our sandwiches yet? How many times have I refilled my glass of Scotch? What is Morris wearing? How scraggly is his white beard? I don’t want our last meal to be too maudlin. I don’t want to create a false sense of closure. I don’t think that death necessarily closes anything. I want Morris to enjoy his sandwich and to be able to get a kick out of hearing a eulogy about himself — is what I’m writing a eulogy?

It’s a unique position he’s in, so close to attending his own funeral; not many people will get to experience this. I want to let him make whatever he wants to make out of it. I don’t wish to be too self-absorbed about the whole thing, but at the same time, I don’t want to leave without trying to convey how deeply important he is to me and how much I care about him and how much I will miss him.

One of the many parts of Morris I carry around with me is a voice that reminds me not to take myself too seriously, but also to be very serious about what I’m doing and very serious about how I choose to treat people. If this is, in fact, a eulogy, I know that he would not approve of me using the form to anoint him as a higher moral being. He would not want me to blab on — like that old man in my dream — about the extraordinary life he has lived, about all that he has experienced and struggled through, as well as all the people he has managed to touch. I know that Morris is just as complex and flawed as any of us. Yet since the date has been set for his assisted death, a fear keeps popping into my head; it happened just the other day, as I was in the cereal aisle at No Frills. “With Morris gone,” I thought, my heart suddenly thumping, “how will anybody know what is right and what is wrong? Who will be here to remind us of what is meaningful? What will become of the world without Morris?”

So here we are, across from each other, with Scotch and sandwiches. This is the last time I will see Morris’s face in the flesh. This is the last time he will see mine. When I was in my late teens and early twenties, Morris often told me that I resembled a young Mordecai Richler, a thought that filled me with a sort of giddy hope: if I didn’t have the talent to be a writer, at least I looked the part. And when I was a bit older, he told me that I looked like the conservative columnist Charles Krauthammer. I am still not sure whether the latter was meant as an insult or a compliment.

When I first showed my partner, Mira, a photograph of Morris, before the two had met, she said, “Wow, I didn’t picture him to look like that. He looks southern.” I had never thought of Morris as looking southern before, and I’m not even sure exactly what this means, but since Mira pointed it out, I have detected a certain glint in his eyes. I don’t know where it comes from.

Now I’m thinking about Mordecai Richler again, and how Morris gave me the last book Richler published, On Snooker, when I was eighteen years old, and signed it, “To Jules, who won’t be easily snookered.” Not long after that, Morris and I played a game of pool in the now-defunct bar under the Greyhound bus station. He didn’t know how to hold a cue properly, and I don’t think he sunk one ball, but he seemed to enjoy himself thoroughly. In his early seventies, not long before he died, Richler described life as a “brief flicker of time.” It’s a phrase that has stuck with me. And at this moment, I feel struck by the good fortune that my brief flicker and Morris’s happened to have overlapped.

Like Morris, I don’t have any mystical ideas about life after death. But I do believe that relationships go on, even when one party is no longer around. I believe this because during much of the time I spend with Morris, I am not physically with Morris, and he has no idea that I am with him. He shows up in my mind daily to tell me that something I’ve written “doesn’t work” or that “it’s good.” When I’m feeling lazy or hopeless, he reminds me that “talent is widespread; it’s a mixture of talent and discipline that is rare.” Like the countless books that I have read from his shelf and the films and theatre that we have seen together, my time with Morris has shaped a deep part of who I am. With luck, at some point in my life, I will be able to pass on what I’ve learned from him to somebody else who, like me, might need to make use of it.

I guess now it is time to say farewell.

Of course there is more to say.

Of course there is more to write.

Of course there is more silence to be had.

Your mentorship and friendship have been so meaningful to me. I will miss you.

Jules Lewis is the author of Waiting for Ricky Tantrum, a novel, and Tomasso’s Party, a play.