In the opening of “Sandman,” the fifth story in Kim Fu’s Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century, Kelly, a chronic insomniac, receives a visit from the title character. He appears at her bedside in the dead of night to dump copious amounts of sand into her mouth. Kelly lies still as a deluge of dust swells through her insides, weighing her down until she drifts into a deathlike slumber. It’s an absolute miracle. For Kelly, “unbroken stretches of consciousness” have dulled the natural highs and lows of life, leaving space for only the most middling experiences: calibrated office chatter, a “vague, lackadaisical” romance. The Sandman eviscerates her daily torpor and offers her restorative rest, a nourishing oblivion — and, to dig a little deeper, the exquisite sense of being chosen.

This story — one of the strongest in the collection — enacts Fu’s twin preoccupations with magic and the featureless landscape of bourgeois life. The book gathers narratives that introduce bizarre elements into familiar settings and warp a litany of habits. And the Sandman’s visit is not its strangest occurrence. Kelly’s tale sits alongside that of the woman who uses a heightened virtual reality machine to ride a unicorn; the kids who discover a haunted doll; the telemarketer who lives a Kafkaesque nightmare in an apartment teeming with insects; and the bride who encounters a sea monster.

In many ways, these stories mark a departure for Fu. Her previous novels, For Today I Am a Boy and The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore, are about childhood and becoming, about finding one’s place in the world and living out scars of the past. Although it shares with The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore the belief that a moment can be piercing and transformative, and that a single experience can break apart the logic upon which a life is built, this latest work is decidedly more immediate and imaginative in its focus.

But Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century is no typical fantasy. For the most part, spectres of the absurd appear in private — alone, in the dark, or else among friends or between spouses — where they are presented as secrets, figments of inner worlds, rather than supernatural events. Like Emma Bovary and Don Quixote, Fu’s characters belong to the literature of daydreams. The Sandman, the doll, the insects, and the sea creature are simply outgrowths of reality, manifestations of tangible needs and desires. In their own screwball way, the stories embark on an ambitious study of human deficiency, which takes aim at our unmet requirements and the myriad ways we deny and reshape our existences as a result.

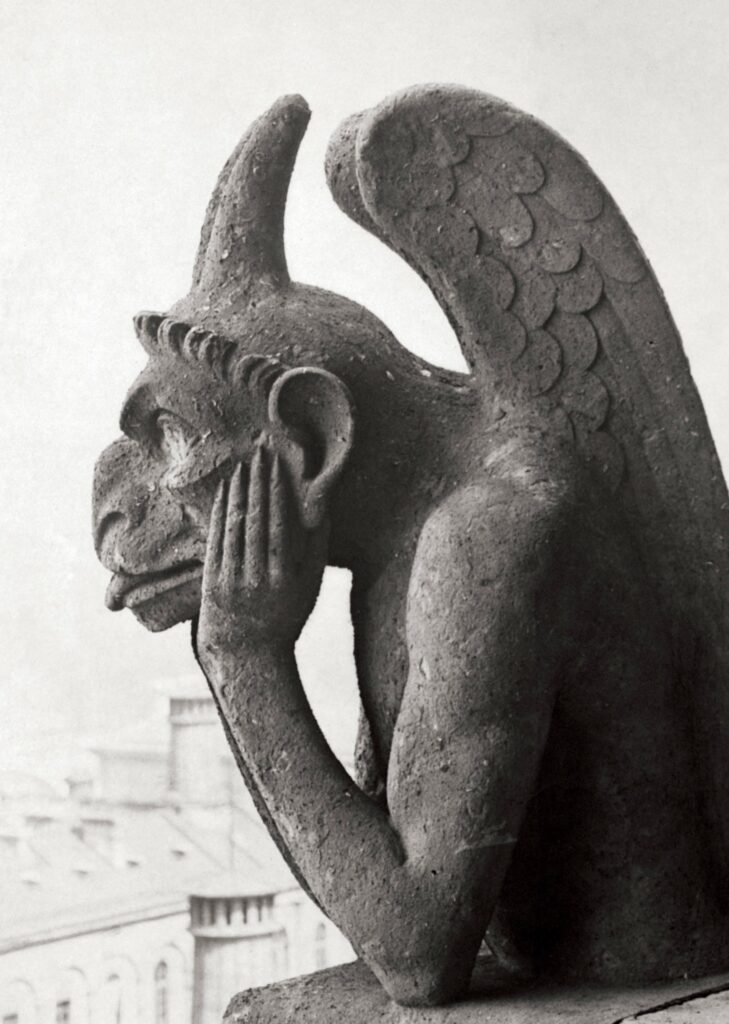

Yesterday’s monsters need not apply.

American National Red Cross photograph collection; Library of Congress

One way Fu wrings out such scarcities is by setting up her characters with new and provocative technologies. Take “Twenty Hours,” in which a married couple — middle-aged, childless, suburban, frugal — splurge on a machine that can reprint the body and transfer one’s consciousness. The device is yet another bulwark against disaster in the twenty-first-century cult of individualism, where “once-reasonable anxieties” about finances and wellness grow “distorted, outsized, habitual,” to the point where the husband admits, “There will never be enough money to make us feel safe.” For a time, the machine sits untouched, a last defence — until it becomes the centre of an irresistible game of murder and revival, where husband and wife take turns killing each other for the luxury of having their partner “not exist for a while.” The real emergency, it turns out, is not the dread of sudden death but the “boredom and disdain” of the marriage. The fantasy, of course, is the union’s abolition.

In the blackness of Fu’s comedy, tedium has mortal consequences. But if these narratives are bleak, they are also darkly gentle. In the case of “Twenty Hours,” which focuses on a time when the husband poisons his wife, his cruelty is balanced by his desire to present her with flowers and soup after her reprinting. Their little game ends in a heartfelt reunion; she smiles upon her return. He is happy because she resurfaces from a place he “could never truly know,” which makes her fascinating once more. It is a warm reminder of the ego-free days of their early romance. They both get what they need.

The fantasies that play out here have a surface-level monstrosity, beneath which lies unremitting, if problematic, tenderness. Wealth, marriage, longer lives: these are the things we are meant to desire. But Fu’s stories reveal a sickness at the heart of those well-trodden ideals and the loneliness and precariousness that persist.

Despite developments in technology, people continue to face major and minor tragedies. They break up, grow bored, lose loved ones, and feel out of control. Murder plots and mythical beings may appear extreme forms of compensation, but they are only as severe as reality itself. Fu points to the intensity of a present where exhaustion is “just a feature of modern life”; where money hoarding is an upper-middle-class norm; and where “peak oil” and “climate change” can be tossed off casually in conversation.

“Do you think it’s immoral to have children now?” one character asks in “Bridezilla.” Her fiancé responds, “Yeah, maybe.” Any simple attachment to traditional values, to the fairy-tale marriage and the big house with four kids, has been overturned: “She wasn’t sure when that had changed, why all these things now struck her as grotesque and fetishistic.” On her wedding day, the bride flees the ceremony and wades out into the polluted ocean.

Although she discards more conventional modes of dreaming, Fu remains enamoured of our frenzied capacity to live in excess of the disappointing present, to exist in a way that is not altogether compliant. Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century celebrates a multitude of needs and desires that are not socially or economically prescribed. Characters hold their secrets, their strangest thoughts close. Such flights of fancy — tinged with desperation though they may be — are what make their lives plausible and survivable as well as enchanting.

Fu doesn’t risk being misunderstood as she enters speculative territory. Unembellished and matter-of-fact, her sentences are the sturdy furniture at the heart of these halls of imagination. Her writing takes the abject, the visionary, and the ordinary as natural parts of the Venn diagram of life and moves calmly through the regions where they overlap. Humbly, the collection proclaims that if our fantasies reveal our inadequacies, they also reveal our creative liberty and the seedlings of other possible futures.

Rachel Gerry is a freelance writer in Toronto.