I first opened Alastair Sweeny’s richly detailed biography while at home in Ottawa, on day 12 of the occupation of the city, February 8, 2022. Snow was falling gently and the distant past was a welcome place.

Thomas Mackay (pronounced Mac-EYE) arrived in what would eventually become Canada’s capital in the summer of 1826, when it was “a wilderness construction camp run by the British Army.” He was thirty-four years old. A stonemason from Perth, Scotland, he had learned from his father “the satisfaction of shaping stone to make it useful and good and even beautiful.” Having been head mason on the Lachine Canal, built on the Island of Montreal earlier in the decade, he would now become a principal contractor for the Rideau Canal.

Mackay had a stonemason’s face. A photograph of him in middle age shows the windswept mutton chops, high forehead, and steady and assessing gaze of a hands-on builder and contractor. “A good practical mason,” as the engineer John Mactaggart described him, who “scorns to slim any work.” When there was difficulty inserting the final keystone of the Sappers’ Bridge, joining Lower Bytown to Barrack Hill, Mackay shouted, “Stop a little, and I’ll fit it in its place.” Then “he came forward and placed the stone with the greatest apparent ease.”

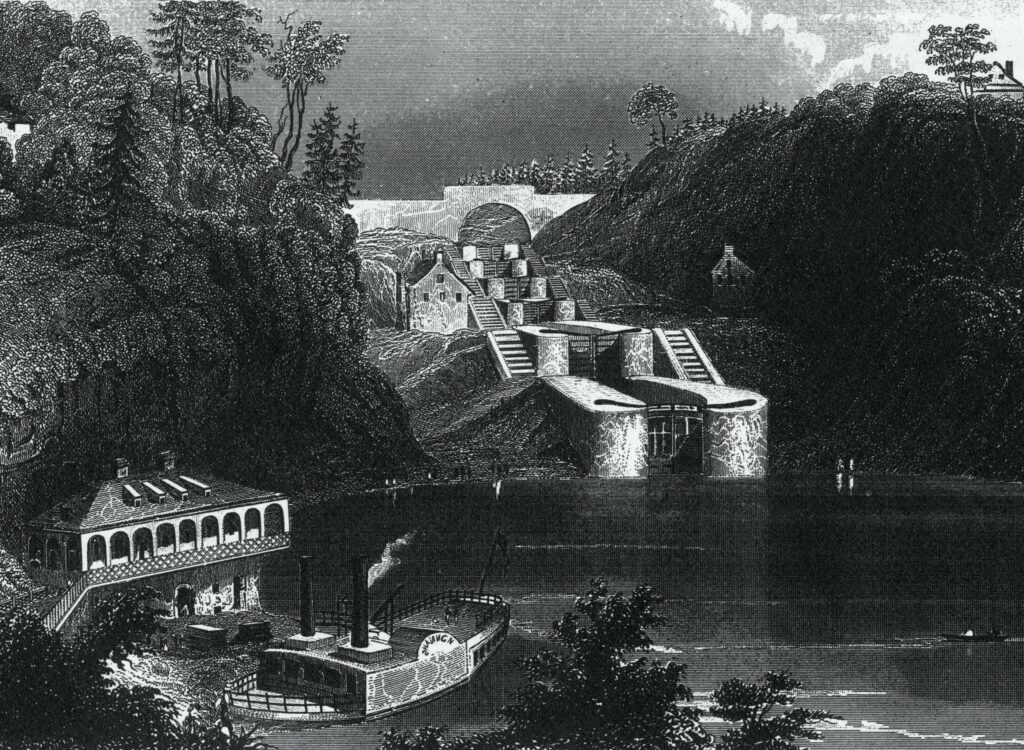

He was a self-made man who made things, including money. He didn’t take his money and leave, however. Unlike all the other major contractors on the canal, Mackay stayed on in Bytown and “used the handsome profits of his masonry work — equivalent to an estimated $60 million in today’s currency, paid in Spanish silver coinage — to help create a community in the wilderness.” At Rideau Falls he erected, in Sweeny’s nice turn of phrase, “a pioneer industrial complex” of mills — saw, grist, shingle, and woollen — plus a brewery, distillery, and cloth factory. “Employees at the mills commonly worked twelve hours a day. Labourers received six cents an hour, boys got two cents an hour, and masons were paid from eight to ten cents an hour.” The work could be quite unsafe, and even Mackay “was not immune to the danger.” In 1851, blankets from the cloth factory were awarded a gold medal at the Great Exhibition, in London.

He was drawn here to carve a sculpture in stone.

Iconographic Encyclopaedia of Science, Literature and Art, 1851; Alamy

Mackay amassed land, founded the village of New Edinburgh (soon a part of Ottawa), and served as a town councillor, justice of the peace, and member of the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada. After the Act of Union of 1840, he sat in the Legislative Council of the Province of Canada for the next fifteen years. He built Earnscliffe (now the residence of the British high commissioner) and Rideau Hall (named by his daughter Elizabeth, who loved Jane Austen) and became “the major driver of the movement” to make Ottawa the capital of a new nation.

Sweeny’s Thomas Mackay is a double biography, of the man and of the founding of a city. It is a local history that draws together many near and distant threads: from the formation of the Ottawa River, “lined with Ordovician limestone laid down in shallow seas 400 million years ago,” to the arrival of fur traders and missionaries in the 1600s; from the inflow of Loyalist refugees in the 1790s to the British navy’s need for alternative sources of timber and hemp during the Napoleonic Wars; from the Highland clearances and crop failures that drove Scots to emigrate (Thomas Mackay among them, landing in Montreal in 1817) to the Duke of Wellington’s iron determination to protect Upper and Lower Canada from American invasion by constructing a back-door or alternative military supply line between Montreal and Lake Ontario.

Wellington’s plan meant that Colonel John By of the Royal Engineers, “living quietly on half pay on his estate in Sussex,” had to return to Canada to supervise the building of a canal, starting at the Ottawa River, moving up the Rideau (so named by Samuel de Champlain for its curtain-like falls where it meets the Ottawa) through the headwater lakes, and then down the Cataraqui into Lake Ontario at Kingston. And it drew Thomas Mackay — whose work on the Lachine Canal had been praised by Governor-in-Chief Lord Dalhousie as “the finest masonry I ever saw”— to build the famous eight entrance locks directly beside today’s Parliament Hill, later described as “a sculpture in stone.”

In Sweeny’s book, all roads and waterways lead to Bytown and “the isolated and unsettled area of the Ottawa Valley.” I was still reading it on day 14 of the siege, learning many things about the Duke of Wellington, the Battle of Waterloo, and the power network of Wellington’s colleagues and staff officers who took charge of Upper Canada. Sweeny recounts Dalhousie’s tour in 1821 of the Great Lakes and Ottawa Valley, in a birchbark canoe “manned with 14 of the engagés of the North West Company.” As Dalhousie put it, “The intelligence & activity of these fellows cannot be described or understood without seeing them. . . . Such joy & such exactness of time to the paddles.” Equally absorbing are the details of the Rideau Canal, “paid for almost entirely from the stores of silver booty taken by Royal Navy frigates during the wars against Napoleon” (the treasure was “packed in barrels in fortresses at Halifax, Québec, and Montréal”). It was a massive engineering project, laboured upon by a workforce of “disbanded soldiers, displaced farmers, or desperate paupers”— immigrants all.

Under what circumstances, I’ve often wondered, does our appetite for fiction get displaced by a hunger for non-fiction? I’m thinking of a friend’s aversion to novels after the death of her husband. Thinking, too, of the American author and translator Lydia Davis’s tart comment in 2013: “These days, I prefer books that contain something real, or something the author at least believed to be real. I don’t want to be bored by someone’s imagination.”

Maybe it’s when events hijack us, when the real world gives us more plot twists than we can handle, that a novelist’s concoctions seem irritatingly beside the point. Then a respite from current events is better supplied by well-researched facts about an earlier time that frames and deepens and balances our own. The sense of continuity brings perspective and can act as a restorative and a relief.

Mackay’s fellow builder John Mactaggart, often quoted by Sweeny, wrote with almost boyish wonder, in his Three Years in Canada, that in 1826 “material are just for the lifting. . . . Nature was never so kind. Plenty of timber, plenty of stone.” Never so kind and never so tough. “I was torn off my horse’s back, and left among the briers again,” as Mactaggart said of their passage through thick forest. “Mr. Mackay, as good a Scotsman as lives, laughed, and I was almost inclined to curse him; the fellow being a good horseman, and used to the rough roads of Canada, could keep his seat on the saddle in a way, but the skin of his legs was partly peeled like my own, and his clothes torn in various places.”

At that point, during the initial planning phase of the canal, they were exploring north of the Ottawa River, where an Algonquin hunter named Grey Bear had let it be known there was iron to be found. “An expedition was arranged,” Sweeny writes, “but it failed when the Algonquin women vigorously argued that showing the whites where to find precious rocks would cause the wildlife to flee from their territory.”

Despite this eloquent tidbit, Sweeny’s is not a book to consult for the latest take on settler colonialism. It accepts as given that the British authorities doled out land as they pleased, coming into conflict on occasion only with speculators who had got there first. Predictably, the expedition “on horseback up the Gatineau River and into the bush” went ahead anyway with a different Algonquin guide and with Mackay at its head.

For a time, we lose sight of Mackay, when the author delves into the 200-kilometre canal itself, its forty-seven masonry locks, fifty-two dams, and long stretches of calm water. Sweeny follows the fates of a large cast of characters. I never lost interest, however, trusting that Mackay would reappear, and he does.

Sweeny describes Mackay as “a big man, and hard to cross.” He was also clever, adapting his methods of construction for the Ottawa Valley: “As winter approached, they drilled the stones laboriously by hand, then at freeze-up they poured water into the holes. The expanding ice naturally split the rock. In the late winter and early spring, the masons then chiselled the stones to the desired shape and size.”

This is the first biography of Mackay, and it’s a smart way to tell the story of Ottawa. If I sit at my desk, I can see a tired shelf sagging under local histories leafed through or only half read, since my attention flags when no central character anchors the events. Sweeny gives us a public-spirited man active in the life of Bytown, as it grew and prospered around and because of him — a “ruddy faced, forceful man” involved in the dramas of pre-Confederation Canada, at which the author is a dab hand. (Sweeny has also published a biography of George-Étienne Cartier, the Father of Confederation from Canada East.) And there are generous pages devoted to Mackay’s extended family, especially his gifted son-in-law Thomas Keefer, who turned the large property known as “Mackay’s Bush” into the residential district of Rockcliffe Park, a part of Ottawa that Humphrey Carver, the urban planner and author of the wonderful Compassionate Landscape, called “quintessentially Canadian: water, forest, rock.”

During those unbelievable days this February — stuck in an oppressive rut of official inaction and bewilderment in the face of all the massive trucks, fumes, horns, and harassment that wreaked havoc on the city — I appreciated the work the author has done. Just as I did his recreation of the work — the dedicated building with stone — done by Thomas Mackay. Sweeny spent fifteen years researching this book: a hobby, he writes, that became a passion.

Yet, inevitably, aspects of Mackay’s life remain obscure, since he left few personal or business papers and virtually no correspondence. I’m reminded of the epigraph in Penelope Fitzgerald’s novel The Blue Flower, a quotation from the German poet Novalis: “Novels arise from the shortcomings of history.” Surely that’s true. We long for more than the historical record gives us, and we hope to find it in fiction: a probing of human motivations, personal contradictions, the inner weather as well as the outer.

I wonder what the right novelist might make of this man who amassed more and more wealth as his children fell like leaves. Sixteen sons and daughters, most of whom died either of smallpox or typhus or tuberculosis or drowning (“in the Ottawa River while tobogganing with friends”). We learn that not one Mackay boy survived beyond his twenties and that only three of the girls outlived their aged mother. We get tantalizing glimpses of Mackay on the library balcony at Rideau Hall, playing his “mournful bagpipes,” bewailing the loss of his children. We also find him alone in his tower, hearing “the wolves howling at night, and the drumming of the Algonquins who camped every summer across where the Ottawa River meets the Gatineau.” The devout laird of Rideau Hall, one of whose skillful hands was mutilated by a circular saw in his own mill, led family and friends in the singing of old Scottish hymns and laments.

Thomas Mackay died in that house in 1855, at the age of sixty-three, of stomach cancer, having seen a considerable part of his fortune bleed away in railway investments that proved unlucky. A character made for Thomas Hardy. But, perhaps, history does beggar fiction in the end. What novelist would have the nerve to imagine something so bold, so right, so satisfying, so at long last, as the present laird of Rideau Hall, the thirtieth governor general, Mary Simon?

Elizabeth Hay is the author of Late Nights on Air, winner of the 2007 Scotiabank Giller Prize.