Walking may be the closest thing to the universal human activity, but every walker, like every footprint, is unique. Some people saunter and wander and ramble. Others plod along, blocking the path for those trying to power ahead. Many just proceed onward in their own sweet way, one foot pursuing the other, indifferent to the pedestrian fact that they are doing something worth pondering.

Yes, we can over-think these things. Not every moment needs to be mindful, particularly if your contemplation budget is already fully allocated to slow eating and meditative sipping and in-the-moment gratitude and Tantric whatever. Socrates taught in the streets, and Aristotle was the original peripatetic, but you’d never catch them carrying on about orthotics or ruminating on gait analysis. Perhaps walking is best left alone — an unexamined act that is simply the un‑fancy, ground-level consequence of living and breathing.

Not to go all Forrest Gump in the presence of an exquisite and profound writer like Tim Bowling, but daily life is a lot like walking: a series of ephemeral and repetitive moments that can accumulate into purpose and meaning and — why not? — beauty. But only — and here’s the challenging caveat — if you approach them with the kind of studied introspection that Bowling brings to every subject he scrutinizes in The Call of the Red‑Winged Blackbird.

At first, the vivid Audubon image on the cover of this collection of essays made me think that Bowling and I were simpatico on the whole commonplace-extraordinary juncture — that my happy attentiveness to the blackbirds’ red wings and keening calls as I quick‑step through my local ravine to avoid killer cars and to sample full-throttle nature on a destination-driven shopping trip (bargain Pinot Noir, with bonus exercise!) could somehow be compatible with his deep psychic peregrinations. But even we manic urban pacers end up being a little too singular for one another’s comfort. Compared with Bowling’s frantic moonlit vagabondage, brimming over with the kind of unsparing meditations and far-flung literary references that come with sleepless solitude, my strolls are just those of a superficial café‑society flâneur.

Searching for something that’s lost.

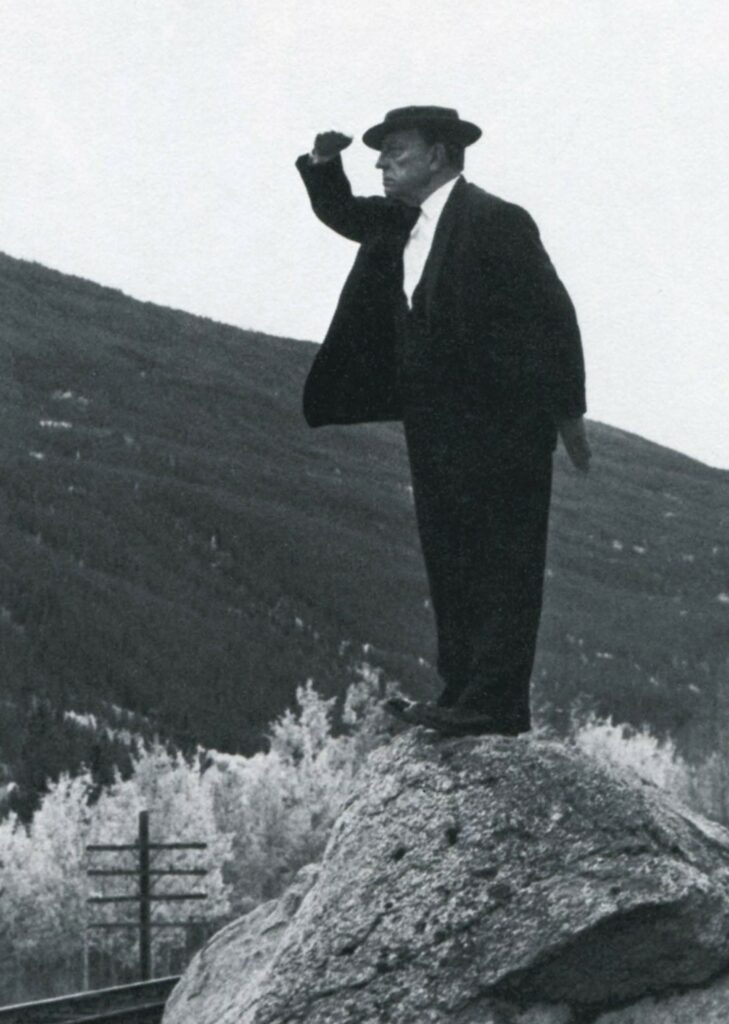

The Railrodder, 1965; Alamy

Walking for me is an energetic pleasure and an end in itself, one best enjoyed with a chatty companion whose random conversation speeds the journey and provides a diversionary soundtrack to the unspooling landscape. Bowling is a confirmed solitary, and a walk for him is more a form of distilled alienation, the nightly shortcut to a state where he can escape the pains of the world and search for deeper meaning and hidden memories in not so splendid isolation.

Like Tim Bowling, and yet quite unlike Tim Bowling, I find that walking puts me at odds with the world: not the world of circumscribed spaces for books and ideas and well-placed words that is the introvert’s version of truer reality but that other world, the noisy one of jabbering phones, jumpy attention spans, and empty busyness. There — and now Bowling starts to leave me behind —“the reading culture of the past several centuries is, like vaudeville and wild salmon and the Amazon rainforest, doomed to extinction, gone the way of nationhood and manners and other quaint rejects from a time when public figures at least paid lip service to values other than money-making and money-counting.”

That’s a lot to bemoan in one go, even for an out-of-sync poet-essayist with a penchant for generic world-weariness. That’s especially so when it turns up as an aside in a neatly meandering essay about a 1965 National Film Board production called The Railrodder and the silent-film star Buster Keaton, whose successful shift from vaudeville to movies ought to diffuse some of the ambient pessimism. Bowling has a gift for coalescing disparate thoughts and unpredictable verbal veers into free-ranging artisanal prose — about childhood books, love letters, his first time on skates, the fundamental connection between cursive writing and elaborate sentence structure, hermits, more hermits, the cherry trees of youth, the post-lunar life of Neil Armstrong — but keeping to the point is not his thing. You read Bowling to go off the rails, as it were.

Good essayists recognize that their art is, in large part, one of dexterity: developing deep thoughts and universal themes on a miniature scale, at a personal level, in an easygoing if not necessarily easy style that aims to connive and cajole rather than lecture and hector. But once they get going on all these “and another thing” laments, eyes glaze, and they’ve turned the companionable reader into a helpless bystander. What ought to be intimacy on the page is thus transformed into a self-regarding rant.

Such writerly dissatisfaction prompts Bowling to investigate other extreme solitaries in hopes of finding some kinship of understanding, though many such figures end up being overly distracted by the practicalities of survival or are too religious in their renunciatory spiritual quest. So instead he seeks iconic validation for his own disengaged state: If the reclusive Michel de Montaigne can write popular autobiographical essays about solitude — and sadness and fear and cannibals — by retreating to his book-lined Dordogne tower, why shouldn’t Tim Bowling do much the same? Merely drop the cannibals while peppering in some astronauts and salmon fishing and a mother’s imitation of a blackbird call, all from the lonely perspective of a night walker tramping through Edmonton’s riverside woods.

But there’s a noticeable difference in literary intent. Bowling is a solipsist by nature, as well as by style, who finds it hard to make room for an outside audience. That’s a lyric poet’s strength, perhaps, but a risky routine for an essayist aiming to connect the extraordinary with the commonplace. He’s not at all shy about proclaiming his introversion and his increasing detachment from other humans, from day-to-day responsibilities, and, indeed, from almost anything that is locked into the mundane present, as opposed to the richer fabricated past of literature and memory. And while you could say that this is exactly what makes him a Guggenheim-winning writer — one who can bring to life the water-bound world of his Fraser River childhood in fluent poetic language that is as inviting as it is invigorating — there’s sure to be something missing in an observer of simple glories who can’t quite bring himself to consort with the world as it is.

John Allemang has his stopwatch ready for the Paris Games.