Nothing is ever changed at a single stroke, I know that full well, although a person sometimes wishes it could be otherwise.

— Margaret Laurence

Believing that real life happens elsewhere is one of those particularly Canadian traits — both in our people and in our fiction. The talented among us really only “make it” when they get to the city. (Or, if they’re from the city already, to America.) Canadian books are full of escape artists, yet literature can also turn the plainest corners of the earth into shrines. In doing so, it can draw universal response from radical regionalism. Margaret Laurence knew this and believed that creative writers were obliged to nail down their particular piece of this strange country.

In a sense, then, my work is already done, as my particular piece is the farmland of Manitoba, some forty kilometres from Neepawa, Laurence’s hometown and the pivot of her Manawaka series. It’s a strange kind of luck to find oneself living within an established canon. It’s like being an extra on stage, hanging around the set long after the director has left rehearsal. I also think of it as a blessing — especially when the writer is one as perceptive and talented as Laurence. She is proof that any place is as good as the next, each locale its own centre of the cosmos, with its own destiny.

When I grew up, Neepawa was the “big town,” which meant it had a Dairy Queen, farm equipment dealerships, and movies at the Roxy. Laurence and her books didn’t figure in my world at all, though. I was vaguely aware of her but not as a writer, let alone as someone who had presented these very streets to the world several decades earlier. I didn’t read anything of hers until my late twenties, when I was living in Scotland and pining for home.

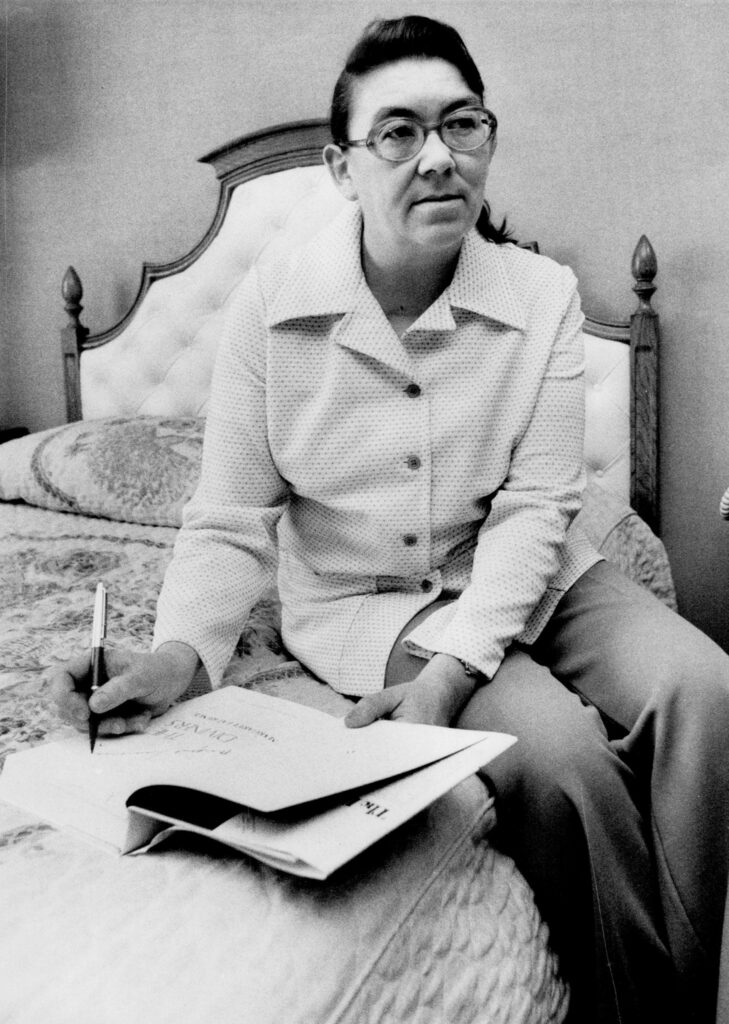

Signing a copy of The Diviners in 1974.

Dick Darrell; Toronto Star; Getty Images

Born in 1926, Laurence had her problems with Neepawa, grievances familiar to anyone with small-town roots. For one thing, she wanted to stop being seen as “Bob Wemyss’s daughter.” She also despised the area’s hard-edged puritanism and the Calvinists for whom sloth (sitting around and writing) was the original sin. She had no truck with local gossip, which, like bartering in some foreign bazaar, is a game one is expected to play.

Of her early education, Laurence wrote in her memoir, Dance on the Earth, “I feel cheated, not by my teachers but by the society in which I grew up.” I can’t let my schooling off the hook as easily as she did: my high school English teacher assigned only books that were also movies. This allowed us (and presumably her) to forgo the reading altogether. And the same puritanism Laurence fought all her working life thrived in those halls. I remember how our study of George Orwell’s 1984 was reduced to a single viewing of the Michael Radford adaptation, starring John Hurt, during which our profoundly devout instructor would stand by the television, ready to hold a placard over the many scenes she felt would corrupt our innocence. The irony was lost on us all.

As was introspection. My grandmother, a stoic farmer who saw more virtue in ignoring people than in scrutinizing them, shivered whenever Laurence’s name was mentioned — a rather common reaction. Her beef with the author wasn’t that she told untruths but that she was “unkind”— another way of saying her characters hit a little too close to home. Those grains of truth rubbed folks raw, and the idea that our faults were broadcast to the country and beyond irked not a few.

Yes, Laurence’s work is truthful about this area, which is wide open and deeply rural. An outsider is not necessarily a foreigner but one who deviates from the usual: artists, minorities, the liberal-minded, the lucky. She captured so well the strict self-reliance, the rejection of empathy, the contempt for weakness found among the people. Nobody under her gaze was as simple or singular as they seemed. One was being weighed against one’s background: the hardscrabble pioneers, the repressed guilt over society’s treatment of Indigenous people, the Depression. She knew, as so many don’t, that suffering shouldn’t be a matter of one-upmanship.

That radical regionalism of hers makes me believe Manawaka is on par with Dickens’s London or Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, worlds of the mind that are almost synonymous with national literatures. The imaginings are there, as is the intricate web of characters. Laurence has always had her critics, but I read The Stone Angel as almost Canada’s David Copperfield or The Unvanquished — a cultural touchstone that brings universal recognition.

Many find local icons a tempting target, and Laurence’s reception on her home soil sometimes made her feel like the Biblical Ruth —“in tears amid the alien corn.” One cannot write well from hate or arrogance; it was love and vision that drove her. Far from an indictment, her work was a call for change. She was a non-conformist and a progressive, championing women’s rights, access to abortion, and racial reconciliation.

In today’s Manawaka, thirty-five years after Laurence died at the age of sixty, the topics of unwanted pregnancy, abortion, racism, and environmentalism are still touchy. In Laurence’s hands decades ago, they sounded to locals like castigation from a woman who had long ago left Neepawa for a life elsewhere (complaining being another local sin). Although she had moved away, The Stone Angel was something of a mental homecoming, an attempt to come to terms with where she came from, and therefore to come to terms with who she was. She published the book in 1964, but that larger journey never ended for her, just as it doesn’t for most. Had I read the novel when I was young, I’d have had a jump-start on the opportunity both to see my community on the page and to face its darker side. Perhaps most of all, it would have helped to know that from this place sprang an ardent defender of human rights, equality, and truth — one who left proof of her beliefs.

Laurence once said she was a person of hope but not of optimism. Some of the change she sought has finally arrived in Neepawa. A recent spate of immigration has softened it somewhat. Growing diversity is shifting attitudes, making the town more friendly and accessible. The local hockey team has even changed its name from the Natives to the Titans. Laurence will continue to speak to the universal. But in time, her books may show those of us from Manawaka — those who have stayed, those who have left, and those, like me, who have returned — who we were, rather than who we continue to be.

J. R. Patterson has contributed to The Atlantic and many other publications around the world.