As a new kid in elementary school in southeast Calgary in the early 1970s, I was assured by classmates that an old brick building just south of town had once been a house of horrors, complete with torture chambers in the attic. (I later learned it had been a home for orphans, the poor, and the aged, established by the nineteenth-century missionary Albert Lacombe.) Judging by the whispered tales of terror, hints of the supernatural, and eerie trappings of decayed buildings and family curses running through Brief Life, Kevin Marc Fournier likely spent part of his youth listening wide-eyed to similar legends. And as a Winnipegger, he probably heard the local tales of ghostly nocturnal presences at St. Andrew’s on the Red, a stone church north of the city.

In his first adult novel, Fournier brings a gothic sensibility to a familiar Manitoba setting. Brief Life is set in the fictional town of Whittle, along the fictional Whitetail River, within view of the forested plateau known as Riding Mountain and adjacent to the Yellowhead Highway. Readers may recognize this region as that of Margaret Laurence’s Manawaka, the town inspired by her childhood home of Neepawa. Like Laurence, Fournier examines the unfinished business between white and Indigenous communities in a transition zone between farm and forest country. But where Laurence’s books are examples of prairie realism, Fournier — who previously wrote a young-adult fantasy about a teenager who travels to an underworld known as Suicide City — draws from horror and magical realism.

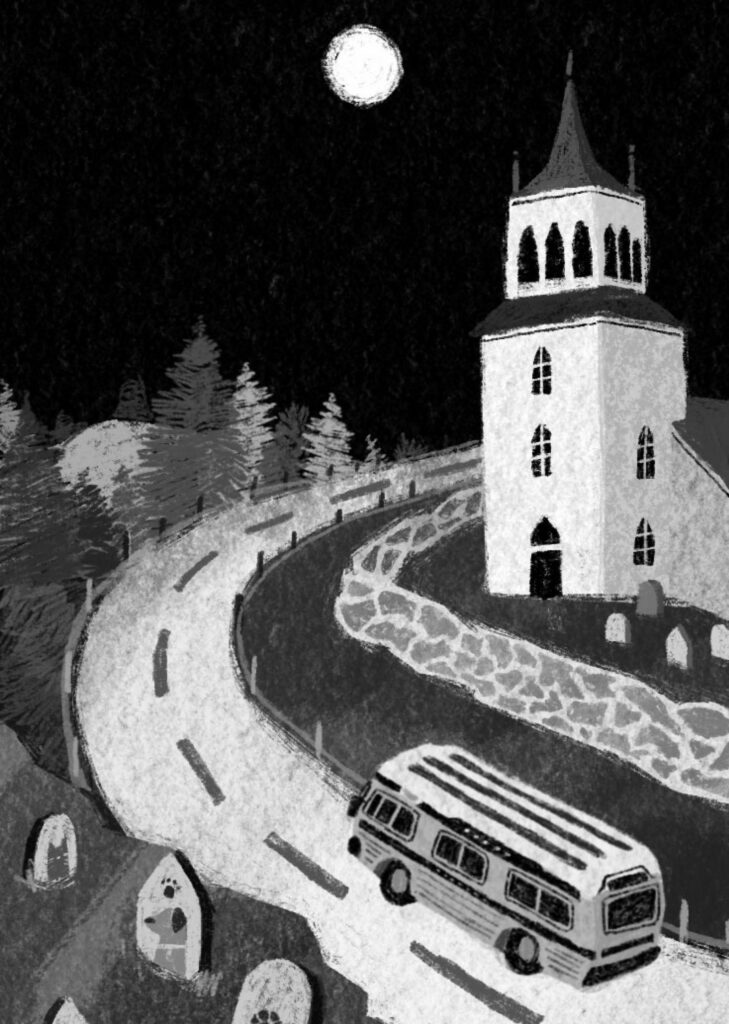

Brief Life begins as a biographical novel of Addy Mack, seen in the prologue travelling by bus as a teenager from Montreal to Winnipeg to attend the wedding of Nora, a surrogate mother who was her actual mother’s best friend. The trip and the prologue are both cut short somewhere between Thunder Bay and Kenora, Ontario, when Addy sees something terrible in the bus’s bathroom mirror: “Suddenly someone — or something — else was there, scuttling in through the door and flopping abruptly up against the glass, its mouth open wide.”

With this, Brief Life becomes a very different sort of book: a sometimes fantastical saga of three generations of extended families and neighbours in a town that often seems cut off from the world. Much of this story is seen through the eyes of Addy’s mother, Casey, and of Nora. In its dozens of characters and blending of day-to-day community life — weddings, births, local elections — with second- and third-hand accounts of unexplained phenomena, Brief Life feels more like Gabriel García Márquez than like Margaret Laurence. Fournier could have titled it Fifty Years of Relative Isolation.

Headed toward a fantastical saga.

Nicole Iu

Strange things happen. Sometimes — as when we read that Nora’s grandmother continues to grow new teeth throughout her life, turning milk pink when she drinks it to ease the pain of bleeding gums — these happenings are simply an accepted part of living. At other times, such as during a plague of pet disappearances, the community buzzes with speculation. Minor characters make odd and menacing pronouncements. A minister, tired after a wedding, confides in Casey that his parishioners have minds “like month-old cartons of milk, you open them up and the smell makes you sick to your stomach.” In another disturbing encounter, a stranger talks with disgust about how “filthy” children are.

It was a subject of frequent discussion among Whittle’s children, almost all of whom managed to convince themselves that they had heard the sounds of ghostly drumming coming from the empty building on full moon nights. Others said those drumming sounds came not from the school itself but from a thick grove of crabapple trees behind the building, with dark purple leaves and little nasty apples, that was believed to be growing over the site of a mass and unmarked grave where the bodies of schoolchildren had been surreptitiously and unceremoniously buried.

Like the real-life St. Andrew’s on the Red, the Stone School becomes the subject of playground dares. High schoolers get added thrills from their illicit drinking and drugs by consuming them in the abandoned building. In one passage, Casey, in her teen years, dares herself to sleep there alone. “If you went up to the second-floor dormitories on certain nights,” local children tell one another, “and if you went into the washrooms and said a certain combination of words, or performed some simple ritual . . . you would see reflected in those bathroom mirrors the horrible crimes of long ago being re-enacted before your eyes.”

The superstition anticipates Addy’s unsettling experience on the bus and calls to mind the legend of Bloody Mary. Thrill-seeking kids still chant the name and look into a mirror to see the ghost or corpse of Queen Mary I, who had 300 Protestants executed in the sixteenth century. And in what may be a sly reference to Stephen King’s The Shining, one of Nora’s uncles seeks to buy the property to make it into a hotel featuring a giant hedge maze.

The suggestions of supernatural terrors are connected to the building’s past as a residential school. Misdeeds are generally presented at a remove of time and through a haze of legend, though the disappearance of the town’s pets may allude to the state-sanctioned abduction of children. Fournier uses fantasy to hint at the relations between white and First Nations communities in other ways: One of Nora’s aunts, who as an Indigenous child was adopted by a white family, is hired as a nanny by a high-powered professor and given the special duty of sleeping an extra few hours a night for her employer. Before a year’s employment is finished, the professor becomes a vampire of rest, stealing all of the aunt’s sleep and with it her dreams.

Amid these magical realist happenings and horror motifs, Brief Life is a small-town coming-of-age story that explores family and community secrets, social status, and how teenage girls discover the world through trial and error, as well as books. Whittle is filled with puzzling people and events; it contains mysterious multitudes that are worth trying to decipher.

Bob Armstrong is the author of Prodigies, an award-winning Western, and, since 2002, the speech writer for Manitoba’s lieutenant-governor.