On the south side of Harbord Street, in Toronto, there used to be a small ground-floor bookshop, the white paint peeling around the trim of the dust-caked front window. It was open at erratic hours. Sometimes I’d swing by after school, and if I was lucky, the owner would unlock the door, a grudgingly unfolded look in his eyes, his white beard crooked from sleep. Wordlessly, he’d return to the single bed in the back, sit atop a wool blanket, and light his pipe while I quietly browsed the unruly shelves. The smell was more pungent than in other used bookstores in the city. Beyond the usual mould and dust, there were layers of stale and fresh tobacco smoke, a hint of urine, and something intangible — an aroma that seemed to have been carried over from another century.

Ray Robertson’s Estates Large and Small is written against the backdrop of such a place, in all its vanishing aliveness (the one on Harbord is now a well-manicured coffee shop). The novel is narrated by fifty-two-year-old Phil Cooper, the former owner of Queen West Books, who in the face of the pandemic has been forced to move his business online. Without the shop, his rundown home in Roncesvalles (surrounded by the freshly renovated properties of once working-class Polish immigrants) has become a cluttered warehouse. Phil lives alone, eating and sleeping among stacks of books, all of them emanating their previous lives. During the week, he visits estate sales, buying up the libraries of the recently deceased.

This melancholy act of commerce brings to mind Chichikov, the mysterious protagonist of Nikolai Gogol’s novel Dead Souls, who roams the countryside of nineteenth-century Russia purchasing the deeds of dead serfs. Both Phil and Chichikov deal in a sort of spiritual capital, shepherding the residues of the living from one place to another. A book, after all, is a stubbornly undying spirit: it will lie dormant for decades — centuries, even — until the right person opens its cover, jolting it back to life.

Estates Large and Small begins as a loose novel, full of chatty set pieces, characters who keep popping up, lingering in the stalled COVID-19 landscape of online commerce, until a love story creeps into the pages and soon takes the narrative in its grip. Throughout it all, the reader is accompanied by Phil Cooper: to read Estates Large and Small is to soak in his particular essence and voice. We meet him not in a state of depression or caged desire (like so many mid-life male narrators), but rather in a contented, cozy curmudgeonliness. “I haven’t accomplished a lot in my life,” he says, “no children, no lasting long-term relationship, no significant contribution to culture or society — but I’ve been a good bookseller.” The absence of certain middle-class achievements has not gnarled Phil into a gargoyle of self-loathing or crushed him with a sense of failure. He has carved out enough space to enjoy things on his own terms.

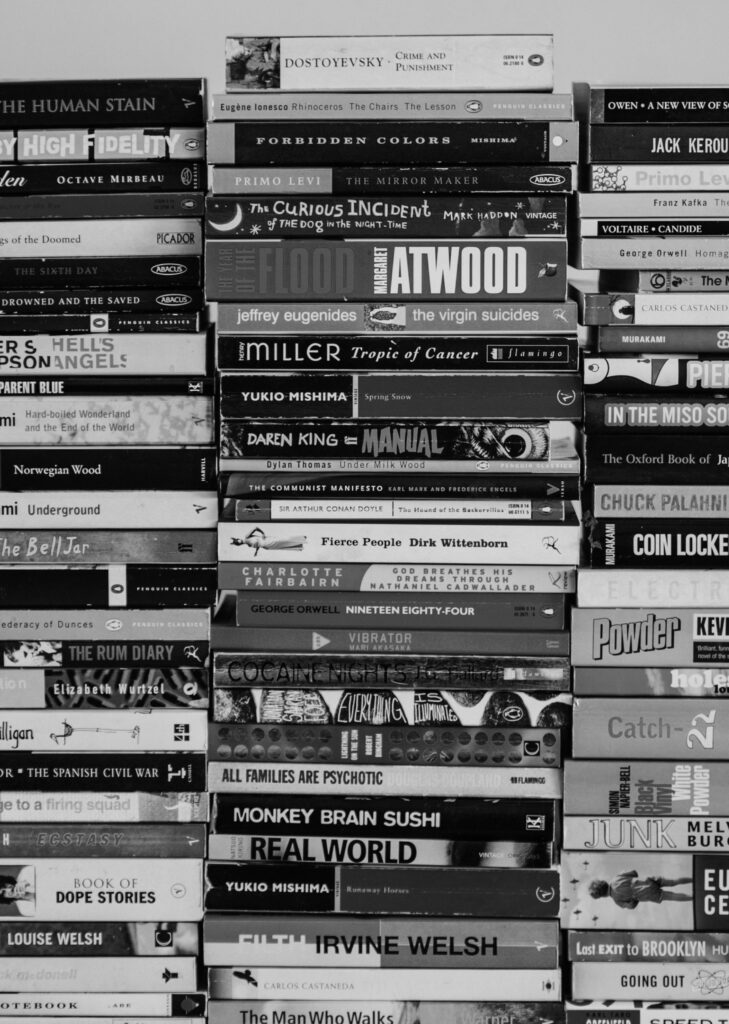

Its plot built upon stacks of used books.

Annie Spratt; Unsplash

After his days of peddling books, Phil spends most evenings snuggled blissfully into a self-made cocoon — woven out of a joint or two, cheap red wine, and Grateful Dead records — where he is lulled into slumber by “the joyful wail of Jerry’s guitar.” Phil’s voice recalls a line from the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard: “I am the sum of my refusals.” His existence is the sum of compromises he hasn’t made. He is a surprisingly untormented guy as a result.

Late in the novel, Phil has a conversation with Caroline — the woman who tugs him away from the pleasures of his contented solitude into the significantly more complex pleasures of a terminal love affair — about Mordecai Richler. “I think the last Canadian novel I actually went out and bought and read when it was first published was Barney’s Version,” she says, lying next to him in bed (where most of their chatting takes place). At times, Phil almost resembles Richler’s great cantankerous, memory-manufacturing protagonist, Barney Panofsky. Like Barney, Phil views the world with a sardonic glare, expounding bitterly on smartphones (“Then she’s tapping away and I know I’ve lost her. The call of the wireless”); on the youth of today (“They seem less like another generation than another species”); on polyamory (“I just can’t get my head around how you can really care about somebody — be really into them, I mean — and still be okay knowing that they’re bumping uglies with somebody else”); on dinner parties (“I preferred to stay home and get high and listen to the Dead”); and on having children (“I’d rather read a book or listen to a record than change a diaper”). But unlike Barney, who courts conflict with an ever-expanding Rolodex of enemies, Phil keeps his more hostile parts to himself. In fact, the characters that pass through this novel — an uptight older brother, a talkative Serbian regular, a fellow stoner and bookstore owner — all appear to really like Phil.

There’s a lot of niceness being passed back and forth. No fights break out, and Phil never imposes his more caustic edges onto the world around him. Rather, he simply shares them privately with the reader, and they can be very funny. When his optometrist diagnoses him with having floaters in one eye, for example, Phil thinks, “Still, it kind of felt like I was an actor being informed by his agent that the good news is that he got the lead in the movie, the bad news is that it’s a snuff film.”

I couldn’t stop thinking about that old bookshop on Harbord Street as I read Estates Large and Small. Those two dank, dusty, and cluttered rooms contained so much life — life at once thoroughly lived and waiting to be reimagined. What happened to all those books when the place closed? Where did the pipe-smoking owner go?

Built, as it were, on stacks of used books, Robertson’s novel is in many ways a meditation on disappearance. How do you read a work with the pre-emptive knowledge that it will end? How do you live in a city that has become unrecognizable before your eyes? How do you love somebody whose future does not include a summer beyond the one in which you find yourself so magically entwined? Sinking deeper into these existential questions, as Estates Large and Small does, scrapes away a sheltering layer of existence, bringing the reader into closer proximity to both joy and loss. Musing about his profession, Phil at one point says, “I was only renting my books.” Indeed, Ray Robertson asks us to think about life as a rental, and to make the best out of it before our lease runs out.

Jules Lewis is the author of Waiting for Ricky Tantrum, a novel, and Tomasso’s Party, a play.