Moshe Safdie was a freshly minted architect in his mid-twenties when he proposed a visionary housing scheme, based on his McGill undergraduate thesis, to the corporation that was building the 1967 Montreal world’s fair. Against all odds, the unconventional project was accepted. But the Canadian government, which was footing the bill, told him that the estimated cost of $42 million (almost $400 million today) was too high and that he would have to make do with $15 million. The disappointed but unbowed architect went back to the drawing board, scaled things down, and produced Habitat, the Lego-like building that has stood beside the St. Lawrence River for more than fifty years. “There was a lesson in this, one that I’ve found myself remembering throughout my career,” Safdie writes in his new memoir. “Sudden duress doesn’t have to mean the end of the story — sometimes it gives you the material for a different story.”

If Walls Could Speak: My Life in Architecture is full of story and duress. There is the story of an idyllic boyhood in Haifa, in pre- and post-independence Israel. In another, the unseasoned tyro who imagined Habitat is catapulted onto the world stage, except that stardom doesn’t automatically produce success. It turns out that building with concrete boxes is complicated and expensive, and Habitat was followed by a decade of stillborn housing proposals for New York City, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Rochester and Saranac Lake, in New York State. The architect turned to his native Israel and recreated himself, designing buildings — large and small — in the complex setting of ancient Jerusalem. Severe duress came from a controversial high-rise project on Columbus Circle in Manhattan, which became a cause célèbre and went down in well-publicized flames. The undaunted architect regrouped and went on to build a string of striking civic monuments in his adopted country: a museum of civilization in Quebec City’s historic Lower Town; a magisterial national gallery and a city hall in Ottawa; an art museum in Montreal; and a public library in Vancouver. From sea to sea.

Writers keep journals; architects, whose imagination is visual rather than literary, carry sketchbooks. With the exception of Frank Lloyd Wright’s famously unreliable An Autobiography, leading practitioners rarely pull back the curtain on their professional lives. After all, architecture is a serious business; money and reputations are involved; and candid recollections of projects and clients can seem like telling tales out of school. Nevertheless, Safdie has been unusually outspoken. In a controversial 1981 article in The Atlantic, he criticized the proponents of architectural postmodernism, naming names and ruffling feathers. “You have no idea how much anger you aroused in that piece,” his friend Frank Gehry said to him years later. “People were just not used to being told off by colleagues in public, and certainly not attacked in such a strong, direct way. I was also upset.”

If Walls Could Speak is similarly plain-spoken as it details setbacks as well as successes and points to “stalwart patrons and determined antagonists.” Safdie’s buildings can be dramatic, even theatrical. But this book is distinctly unpretentious: the tone is intimate and conversational. While the writing occasionally feels excessively upbeat — all architects are optimists — it is uncluttered by the jargon that infects so much architectural prose today. Consider Safdie on the genesis of the Khalsa Heritage Centre in India:

Recalling the grand pool at the Golden Temple and the presence of water at almost every Sikh temple, I proposed damming the valley and creating a series of cascading ponds. The pedestrian bridge arcing across would be reflected in the water. Back at our home office in the United States, I listened to Punjabi music as I worked on a proposed design.

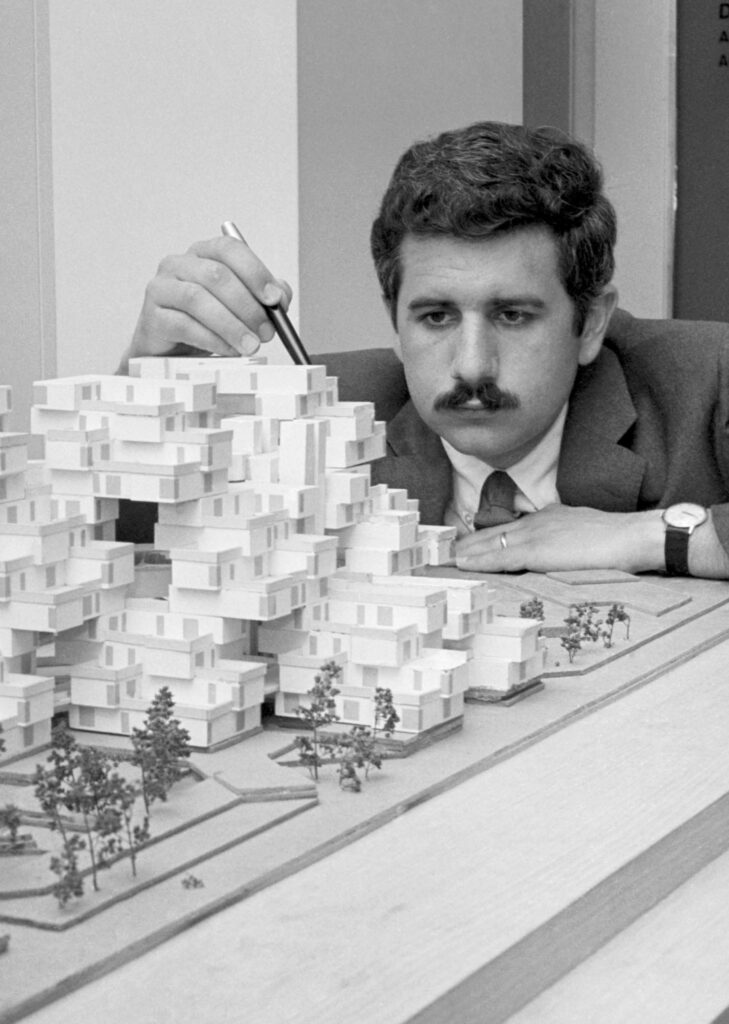

Habitat catapulted him onto the world stage.

Bettmann; Getty Images

The great American architect H. H. Richardson was once asked to name the most important thing in the profession and gruffly responded, “Getting the job.” The reader of Safdie’s memoir learns not only about how an architect works — it is profusely illustrated with sketches, as well as photographs of finished work — but also about the practice of architecture: that is, getting the job. Like all leading architects, Safdie participated in many competitions; some he won, some he lost. A prominent loss was the mammoth National Museum of China, which Safdie describes as “a promising venture that fell apart for reasons I still don’t quite understand.” His firm was a finalist, up against Gehry, Zaha Hadid, and Jean Nouvel — Pritzker Architecture Prize laureates all (an award that has inexplicably passed Safdie over). Nouvel won that competition, although the project appears stalled.

There were also unexpected windfalls. The chairman of Dubai’s largest development company once invited Safdie to a meeting and told his surprised guest, who is, after all, a Sephardic Jew, “We’re going to build a grand mosque here, and I would like you to design it.” The chief minister of Punjab was moved by a visit to Safdie’s Children’s Memorial in Jerusalem and commissioned him to design the aforementioned Khalsa Heritage Centre. The Walmart heiress Alice Walton spent a day with Safdie in northwest Arkansas, where she intended to build an art museum. When he asked her how she planned to choose an architect, she responded, “I have completed my search today.”

The appendix of If Walls Could Speak records more than fifty major projects completed since Habitat. Five decades of practice is an exceptionally long run, but Safdie is not slowing down, even at eighty-four: seven large commissions are currently under way, including a glass-domed conference centre in California (for Facebook), a resort in Japan, and a Chinese housing development that he calls a “Habitat of the Future.”

“There is mystery at the heart of architecture,” he writes, “just as there is mystery in the meaning of life.” The mystery of Safdie is the range of his work: mosques as well as apartment buildings, commercial complexes as well as civic monuments. Thus, we have the over-the-top Marina Bay Sands resort and casino in Singapore, a brashly monumental commercial megaproject in Chongqing, and the severe (and severely moving) Yad Vashem Holocaust History Museum in Jerusalem. The same mind that nestled the rambling Skirball Cultural Center at the foot of the Santa Monica Mountains of Los Angeles also erected an imposing library in Vancouver that recalls the Roman Colosseum. The Israeli garden city of Modi’in, planned in 1989 and currently home to more than 90,000, is a world apart from such intimate spaces as the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, and Alice Walton’s exquisite Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas. (Crystal Bridges is one of Safdie’s best designs, with a series of bridge-like pavilions spanning over water and curved laminated-wood vaults suspended on cables. Clad in copper, the roof forms suggest a family of metallic armadillos.)

“Architecture’s medium is fundamentally material,” Safdie writes. This is a persistent theme of If Walls Could Speak : an immersion in the craft of building. This immersion is accompanied by an energetic willingness to push the envelope of what is considered possible. While architects today sometimes envision odd-looking buildings — twisting skyscrapers and spacey concert halls — the technology to achieve them is usually conventional. There have been those in the past, such as Antoni Gaudí and Frank Lloyd Wright, who experimented with unorthodox construction methods, but architecture is generally a conservative discipline: enough things can go wrong on a building site without tempting fate.

Safdie’s daring (or is it simply willfulness?) was already visible in Habitat. Fabricating concrete modules required giant mechanized moulds and a system of post-tensioned cables to enable the dramatic cantilevers. I was working in the Safdie office at that time, and there was a story that the engineers had proposed adding a single column to reduce cost. Safdie, a purist, insisted that the pyramidal stack of boxes remain column-less. Perhaps surprisingly, this youthful audacity endured. The National Gallery of Canada, for example, was the first art museum to have a skylit lower level, thanks to light shafts lined with reflective material. The recent addition to Singapore’s Changi Airport is a huge toroidal dome of steel and glass that encloses a tiered tropical garden, the startling centrepiece of which is a forty-metre waterfall. Marina Bay Sands, surely one of the most spectacular high-rises in recent memory, consists of three fifty-five-storey hotel towers surmounted by a cantilevered platform carrying a park and infinity pool and resembling a colossal surfboard. “There was a whoooosh,” as Safdie puts it.

While there are identifiable threads in Safdie’s work, notably a fascination with geometry, there is no house brand. In that way, he recalls the Finnish American mid-century modernist Eero Saarinen, another inventive architect, who is said to have coined the phrase “the style for the job.” That may be part of the secret of Safdie’s success. Alice Walton, for one, knew that she would get something unique, a building suited to its natural surroundings and tailored to her particular vision. “There is no simple answer for how to create magic in architecture,” Safdie writes. “And there is no single form of magic. What one might create for a place of entertainment in the heart of a city must be different from the magic one might create for a place of worship, a national memorial, a public library, or a performing-arts center.” But, he rightly points out, “we know magic when we see it.” We certainly do.

Witold Rybczynski was shortlisted for the Charles Taylor Prize for A Clearing in the Distance. His latest is The Story of Architecture.