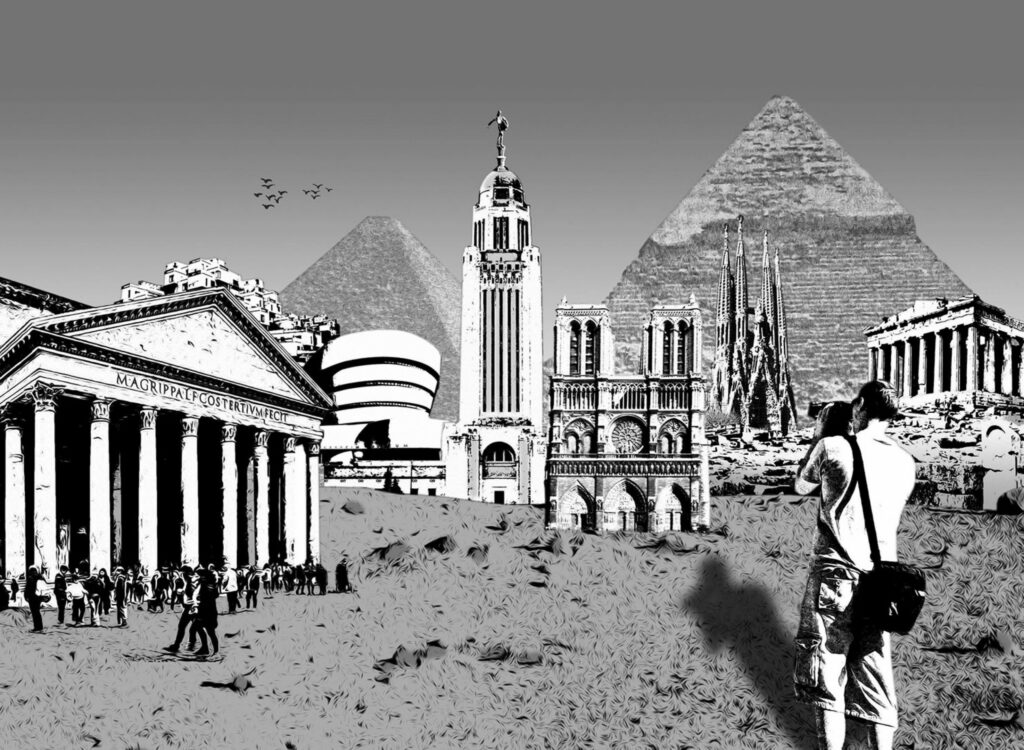

The Parthenon in Athens makes the cut, as does the Pantheon in Rome. Hagia Sophia in Istanbul and Notre-Dame in Paris get the nod. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum in New York City and Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, do too. They’re among the usual suspects in the latest who’s who of important buildings, Witold Rybczynski’s The Story of Architecture. There’s not much to debate about their inclusion as they remain venerated architectural artifacts, not yet torn down or unmentionable because of aberrant associations recently identified.

Somewhat surprisingly, however, Antoni Gaudí gets multiple pages. (Arguably, the Spanish architect is more eccentric outsider than essential practitioner, though perhaps he did anticipate the starchitects of today.) Rybczynski also bestows attention on the Englishman Quinlan Terry, a questionable decision given that many consider him a historicist who’d have done better to copy traditional buildings outright rather than combine their vocabulary with his own talent. But little light is cast on a genius like Terry’s compatriot Edwin Lutyens, who was inspired by many styles and achieved sublime results. The American Robert Venturi is in with reference to Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, his landmark book from 1966, but only one of his firm’s transformative buildings is discussed: the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery in London. Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation apartment block in Marseilles, France, the Radiant City, and his tabula rasa approach to urban planning are deemed influential (however catastrophic that influence ultimately proved to be), but his seminal Villa Savoye isn’t on the radar at all. And while Moshe Safdie gets several mentions, his fellow Canadian Arthur Erickson, an equally excellent and internationally renowned designer, gets none. Many others usually included in this kind of survey, at least in the footnotes, don’t appear either: Tadao Ando, Santiago Calatrava, David Chipperfield, Philip Johnson, Adolf Loos, Richard Meier, Richard Neutra, I. M. Pei, Rudolph Schindler, John Soane, and Kenzō Tange.

A surprising roundup of structures ancient and new.

Pierre-Paul Pariseau

Determining what’s a worthy structure and who is a worthy architect can be a mug’s game, and some encyclopedic overviews have been rather controversial in the past, including Banister Fletcher’s A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method (published in 1896 and regularly updated since) and Nikolaus Pevsner’s An Outline of European Architecture (published in 1942 and still influential in the 1970s, particularly at architecture schools like the one I attended, where modernism was revered). For this project, Rybczynski confesses that he “often favored individual architects” rather than group efforts and “had to leave out many excellent works.”

Learning who’s in and who’s out makes a history like Rybczynski’s an intriguing read, especially when it starts many thousands of years ago and continues to the present, attempts comprehensiveness in a succinct 360 pages, and still leaves room for most of the expected pyramids, Greek temples, Roman engineering marvels, cathedrals, palaces, and postmodern icons, such as Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers’s Centre Pompidou in Paris and Rem Koolhaas’s show-stopping CCTV building in Beijing. A textbook from 2018, Richard Ingersoll’s World Architecture: A Cross-Cultural History, takes over 1,000 pages to traverse similar territory. Suffice to say, Rybczynski faced a formidable challenge. And why attempt to tackle such a challenge if you’re not going to surprise? Rybczynski certainly does so by including Paul Cret’s Château-Thierry American Monument in Aisne, France; Bertram Goodhue’s Nebraska State Capitol in Lincoln; and Albert Speer’s Zeppelinfeld grandstand in Nuremberg, Germany.

Witold Rybczynski was born in Edinburgh in 1943 and moved to Canada with his Polish family when he was still young. He attended Loyola College in Montreal and graduated from McGill University with a master’s in architecture in 1972. He went on to teach at McGill and then the University of Pennsylvania, which perhaps explains his fondness for Montreal’s hometown boy Safdie and Philadelphia’s Louis Kahn, whom he describes as a “late bloomer” like Frank Gehry. Rybczynski is an engaging writer, skilled in making esoteric content accessible to a broad readership. And though one might debate his selection criteria, one generally respects the judgments he makes in The Story of Architecture, his twenty-second book.

Rybczynski begins his discussion not with the Great Pyramids or Stonehenge, as some architectural historians do, but with “one of the oldest surviving buildings in the world,” the Cairn of Barnenez, which “stands on a windswept Brittany headland overlooking the English Channel.” As France’s former minister of culture André Malraux once described it, the burial mound is a “megalithic Parthenon.” Constructed 4,300 years earlier than “what is considered one of the greatest works of ancient architecture,” it demonstrates how “prehistoric man had already felt the need to create commemorative structures that would last — and tell a story to future generations.” In describing the tomb, as he does with many of the buildings that follow, Rybczynski shows how societal aspirations can shape built forms, how a design vision can spur on new construction technologies, and how ornamentation can give meaning to structure.

The Story of Architecture does not attempt to cover “the everyday structures that constitute the bulk of the built environment”— what Bernard Rudofsky once called “architecture without architects”— and it is meant to tell “primarily although not exclusively the story of the Western canon.” Nonetheless, Rybczynski does a good job of weaving in Middle Eastern and Asian architectural narratives for contrast and to show how they have influenced countless buildings in Europe and the Americas. He deftly explains how one era’s or practitioner’s style can transition to another, without implying, as so many similar titles do, that architects simply stopped designing Romanesque one day and switched to Gothic the next. Nor does he suggest that every architect or time has a singular, immutable approach.

In the tradition of Lewis Mumford, the American scholar who wrote about cities and urban architecture with a multi-dimensional perspective, Rybczynski illustrates the many relevant ways we interpret architecture — ways that cumulatively demonstrate its central importance in our lives. Architecture is a testament to what we collectively believe is beautiful, appropriate, and awe-inspiring. It is not simply the outcome of functional imperatives, a desperate desire to get noticed, or just “a fancy name for building,” as Rybczynski puts it.

“Of the roughly one hundred buildings that I discuss here, I have visited about half,” Rybczynski writes near the end of his book. “I’ve climbed to the Acropolis, although I haven’t had the opportunity to go to Isfahan or Kyoto. I’ve toured the Alhambra and the Forbidden City but not the Great Mosque of Kairouan. I’ve seen Louis Kahn’s work in Ahmedabad, but not his National Assembly in Dhaka.” Given the far-flung nature of his content, and considering the pandemic travel disruptions that got in the way of even more field trips, Rybczynski’s journeying is impressive. But seeing photographs of a building and experiencing it are two different things — especially if you’re going to write about it. While reading The Story of Architecture, one sort of senses, without Rybczynski having to say so, which sites he has encountered first-hand and which he hasn’t.

Throughout, I was reminded of studying the Barcelona Pavilion in school — and how shocked I was when I first visited the reconstruction years later. I had a sudden realization that Mies van der Rohe was not the puritanical designer I once imagined but a sensualist, revelling in rich marble and other luxurious finishes. The space was dynamic as I moved through it, not the static stage set communicated by black and white imagery from 1929.

That’s why, in the absence of actually coming into contact with a building physically, it’s so important for books about architecture — be they monographs about specific designers or all-encompassing histories such as this one — to integrate understandable plans alongside inspired, large, and preferably colour photography (reserving black and white for specific historic scenes and for buildings that don’t exist anymore). It’s disappointing, then, that there are so many banal images in The Story of Architecture, especially when most design aficionados tend to look at books like this before they read them, however well written.

None of us need to see, yet again, that same old photograph of Le Corbusier’s Notre-Dame du Haut in Ronchamp, France, especially when there are many superior ones in colour that give a vivid sense of the Roman Catholic chapel’s scale and visceral power. Similarly, why include a small black and white photo showing the curtain wall of Mies’s Seagram Building in New York, which is more or less indistinguishable from the cladding of thousands of imitators? And if mentioning Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, arguably the most famous house in the United States next to the White House, why not insert a beautiful, perhaps unlikely image of it? Rybczynski does present an unexpected shot of Lee Lawrie’s sculptural portal Wisdom: A Voice from the Clouds, which casts New York’s Rockefeller Center in a different light no matter how many times you’ve seen the building on screen or in person. (The Sower, Lawrie’s iconic sculpture atop Nebraska’s capitol, doesn’t fare nearly as well, appearing as more or less a smudge in an uninspired photograph from 1934.)

Section drawings that visually explain a building’s vertical organization are also useful when discussing architecture. The ramp of Wright’s Guggenheim, for instance, is best understood by looking at a section. Similarly, scaled plans and annotated diagrams that illustrate engineering concepts — like how a flying buttress actually works — should be considered table stakes when telling the story of architecture. To not include an abundance of them in a book like this is to underestimate the reader — even if it helps to keep production costs low.

“I was twenty-one when I discovered that architecture could move one deeply and emotionally as well as intellectually,” Rybczynski writes. “That was only three years younger than Le Corbusier when he climbed to the Acropolis and was equally swept away.” Yes, The Story of Architecture would have been a very different book if Rybczynski had focused only on those buildings he had seen and felt, but maybe it would have been even more compelling. Quirky books about architecture, like John Ruskin’s The Stones of Venice and Henry Adams’s Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres, endure because they offer the type of insight that only direct experience and emotion bring, one that intellect and expertise alone cannot replicate.

Kelvin Browne, recently left the contemporary art world to sail in Chester, Nova Scotia.

Related Letters and Responses

Sean Webb via Facebook