It was a disaster. At the very least, it was turning into a highly embarrassing professional failure. By the late 1990s, close to a decade after Frank Gehry had been given the commission to build the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, the project that would transform the downtown core of the city and become one of the new century’s most iconic constructions was in serious trouble. The budget had ballooned out of proportion. The relationship between Gehry and another firm involved had disintegrated. Dissonance among the county and city governments, the Disney family, the Los Angeles Philharmonic and a bevy of critics persisted. The project had gone completely off the rails.

Ironically, what helped break the imbroglio was another Gehry project, which was becoming one of his most celebrated achievements: the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. It opened in 1997, on schedule and slightly under budget, to nearly universal acclaim. Its impact on the community was even more noteworthy: it put the dying industrial town in the Basque country on the map and became a textbook case of how architecture, well planned and well designed, could revitalize a whole city—four million people visited in the three years after the museum opened, almost three times as many as hoped for. If Bilbao, a small city of fewer than half a million people in the middle of nowhere could commission and bring to completion a building by Frank Gehry, how was it that world-class Los Angeles, his adopted home, was unable to?

It did not take long for the Bilbao effect to be felt in Southern California. A movement developed to breathe new life into the project. Construction resumed in 1999 and the concert hall was completed in 2003. When it was finally unveiled, a critic from the New York Times called it “the most gallant building you are ever likely to see” before adding, in a barely exaggerated flight of hyperbole, that it had brought him to “aesthetic ecstasy.” It had taken 16 years to build.

Today, Frank Gehry is widely recognized as one of the most important architects to have emerged in the latter half of the 20th century, but his rise was not without controversy. For a long time, he was regarded as an eccentric outsider who, in the words of biographer Paul Goldberger, “produced buildings that provided spectacle more than architectural rigor.” Doubters were partly silenced in 1989, when Gehry won the Pritzker Architecture Prize, the most prestigious award of his profession, thus affirming his status as one of the most original voices in contemporary architecture. Now, a quarter of a century later, his entire career is being celebrated by a wide-ranging exhibit of his work, which was first presented at the Musée Pompidou in Paris last year and is now on display at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art until March 20, 2016. The show, perhaps the most comprehensive of the architect’s career, presents hundreds of drawings and pictures, and more than 60 models that, together, provide a broad overview of Gehry’s evolution as an architect, from the early 1960s until today. It is accompanied by a beautifully illustrated catalogue, edited by Aurélien Lemonier and Frédéric Migayrou, which constitutes an excellent and highly recommended companion to the biography by Goldberger, the first full-fledged, in-depth study of Gehry’s life and career.

Trevor Waurechen

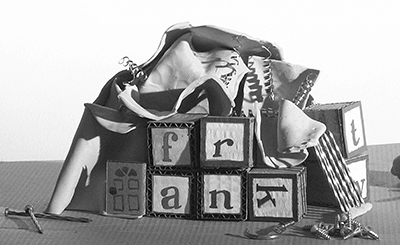

With his grandmother, Gehry erected buildings and freeways out of wood scraps on her kitchen floor.

Frank Owen Goldberg was born in Toronto in 1929, in a Jewish family of mixed Polish and American parentage—his first wife, despite being of the same faith, would later insist that he change his surname to the more gentile-sounding Gehry. His father, Irving, was a difficult and unstable man, with a poor education, who struggled all his life to support his family. He also had a tense relationship with his son—Gehry grew into a chubby adolescent and his father often complained that he was becoming fat. At times, Irving could even get physically abusive. By comparison, Goldberger explains, his mother was a more positive force, one who strongly believed in the importance of education and who took her son “to a museum or cultural event as often as she could.” It is probably fair to say that Gehry would not have considered architecture as a profession without the life-long passion for the arts that his mother instilled in him early on.

Gehry’s maternal grandparents doted on him and were another important influence in his early years. His grandfather ran a hardware store, not far from his home on Beverley Street, near today’s Art Gallery of Ontario, and Gehry would spend many hours there, in the “wonderland full of screws and bolts and hammers and nails and every kind of household gadget.” With his grandmother, he erected buildings and freeways out of wood scraps on her kitchen floor. When Gehry began thinking about becoming an architect, Goldberger explains, he often reminisced about those times, “the most fun I ever had in my life.”

When Gehry was eight, his father moved the family to Timmins, where he distributed and repaired slot machines. This was not a particularly easy period for Gehry, and the five years he spent in northern Ontario must at times have felt like a long exile. But it would be significant nonetheless for this was where he developed a lifelong passion for hockey. Gehry played for decades, well into his sixties, and still regularly attends NHL games in Los Angeles. Far less positive was the anti-Semitism he encountered at school for the first time, but he found solace in friendships with local French Canadians, who often sided with him. As a result, he retains a “big soft spot” for them to this day.

In 1947, when Gehry was 18, the family moved to Los Angeles, where they had relatives. By then, Irving’s mental and physical health was deteriorating—he had suffered a heart attack the year before, after getting into fisticuffs with his son—and doctors suggested moving to warmer climes as they feared Irving “could not survive another Toronto winter.”

At this point, the odds that Frank Gehry would become a successful architect were remote. His family had settled into a dingy apartment infested with bugs and cockroaches, not far from the city’s downtown core. They had no money, and there was no way they would be able to pay for further education, so Gehry got himself a job. In time, he enrolled in free night classes at a local college and later moved, part time at first, to the University of Southern California where, aged 21, after toying with the idea of becoming a ceramist, he finally settled on architecture.

After gaining experience elsewhere, Gehry decided in the early 1960s to establish his own architectural practice. But in those days, pace Hollywood stars and producers, Los Angeles was still a cultural backwater. Artists were few, art museums fewer and galleries showing contemporary works almost non-existent. There was little appetite or market for daring architecture. The city was a very conservative and closed community.

Gehry had always had a curious and inquisitive mind, and his interests went much beyond architecture, so he naturally gravitated toward the city’s tiny but increasingly dynamic art scene. He became friends with Ed Ruscha, Billy Al Bengston, Ed Kienholz and John Altoon, many of them pioneers of installation art and assemblage, people who found inspiration in the streets, dumps and abandoned lots of Los Angeles. Goldberger explains that Gehry “felt comfortable with these artists in a way he did not with other architects,” and, to the growing annoyance of his first wife, spent much of his free time with them, “listening with a careful ear, looking at everything everyone else was doing, and learning what he could from it.” It would pay off handsomely.

Gehry’s friends, but also respected artists elsewhere such as Robert Rauschenberg, had begun using found objects in their work. And thus, Goldberger writes, the architect felt entirely legitimized “about using cheap ordinary materials in serious architecture.” He started to rely extensively on rough-hewn beams, corrugated iron and, somewhat notoriously, chain-link fencing. The exhibition catalogue draws from extensive archival material to show how such components, along with Gehry’s evolving ideas about architecture, were brought to bear in the 1970s, particularly toward the end of the decade, when the architect bought a new home for his family, an old pink-coloured bungalow in Santa Monica. He kept most of the original structure intact, but expanded the house outwards, adding a shell of industrial materials. Some walls inside were stripped, others were left showing unpainted plywood. His own dwelling became a statement for his architectural vision. Gehry could not be accused of merely talking the avant-garde talk. He walked the walk too.

Interestingly, Gehry himself does not use computers very much. For him, they are tools of “execution, not creation.”

By the early 1990s, Gehry had obviously become an important architect, but it was unclear how deep an imprint he would leave on his profession. The advent of computer-aided design changed everything. By then, he had started experimenting with curves and fluid forms, inspired by the sculptural folds of Bernini and other renaissance artists, and CAD software allowed him to give free rein to his imagination. The Guggenheim in Bilbao, the epitome of the new Gehry aesthetics, was the first project to be almost entirely planned with such support—an informative essay in the catalogue explains how Gehry harnessed technology to support his artistic vision. As the models on show at the LACMA demonstrate, very few of Gehry’s subsequent works would have been possible without CAD. And all would have been prohibitively expensive to build.

Interestingly, Gehry himself does not use computers very much. For him, they are tools of “execution, not creation.” As he did as a boy on his grandparents’ kitchen floor, he always starts a project playing with blocks, taping plastic sheets, draping parts with cardboard paper of different colours—Sketches of Frank Gehry, a 2005 documentary by Sydney Pollack, contains fascinating scenes shedding light on Gehry’s creative approach. The architect further moves things around until he is satisfied with form and function. Only then does computer modelling come into play to transform his vision into actionable engineering plans. Had Gehry been born half a century earlier, his legacy would no doubt have been very different.

Gehry has built very little in Canada and thus information in Goldberger’s biography about his work in his home country is scant—indeed, the catalogue contains nothing at all. In fact, the only construction he realized here that still stands is the 2008 renovation of the Art Gallery of Ontario, a very successful project but a rather minor one in his overall oeuvre. This could change mightily, however, if Gehry is allowed to express his full creativity in his ongoing collaboration with local developer David Mirvish. At long last, the Bilbao effect might soon be felt in Toronto.

In clear and straightforward prose, albeit in flattering and not always critical terms, Goldberger thoroughly chronicles the professional ascent of the architect who arguably developed the most arresting visual signature of his age. Yet, the man behind the vision never quite fully comes out of the shadow. Gehry was a passionate workaholic and prescient creator, but he also spent decades in therapy struggling with feelings of guilt, angst and anguish, the consequence of his unsettled upbringing, the bitter failure of his first marriage, the resentment of the two daughters born of that relationship, and much else. Goldberger makes the young Gehry come alive, but the portrait he draws of the mature architect gets sketchier as the years progress. The attention is squarely on the architecture. This is fine as far as it goes, but it leaves the reader hungry for slightly more—Gehry was in New York City on 9/11 and yet Goldberger says essentially nothing on his reaction and very little on his politics in general. A full biography of Frank Gehry was long overdue, but Goldberger’s would have had a deeper impact had he struck a finer balance between the work and life of the “most famous architect in the world.”

Martin Laflamme is a Canadian diplomat, currently posted to Taiwan. The views presented in the magazine are his own.