At this point, every corner of the British Isles has been so hiked, biked, horse-ridden, and driven round by writers, so scraped for meaning and musings, that it’s a wonder the countryside isn’t studded with signs that read: “No littering; no travelogues.” It’s a well-trodden literary landscape, to say the least. Yet here we go again. One more for the road, I guess.

“Been there, done that” comes to mind, particularly when a North American strides boldly into the field, hoping to add his two cents. Almost thirty years ago, Bill Bryson’s pleasantly grumpy peregrinations in Notes from a Small Island captured the nation’s hearts with his detailed mappings of such idiosyncrasies as the protracted discussions and puffing out of cheeks that would result from a proposal to drive from, say, Surrey to Cornwall —“a distance that most Americans would happily go to get a taco.” Two decades later, he released an even grumpier follow-up, The Road to Little Dribbling. The former commissioner for the charity English Heritage remains beloved in his adopted home (it cannot be stressed enough how rare it is in the United Kingdom to find a national treasure with an American accent). Those are some big walking boots to fill.

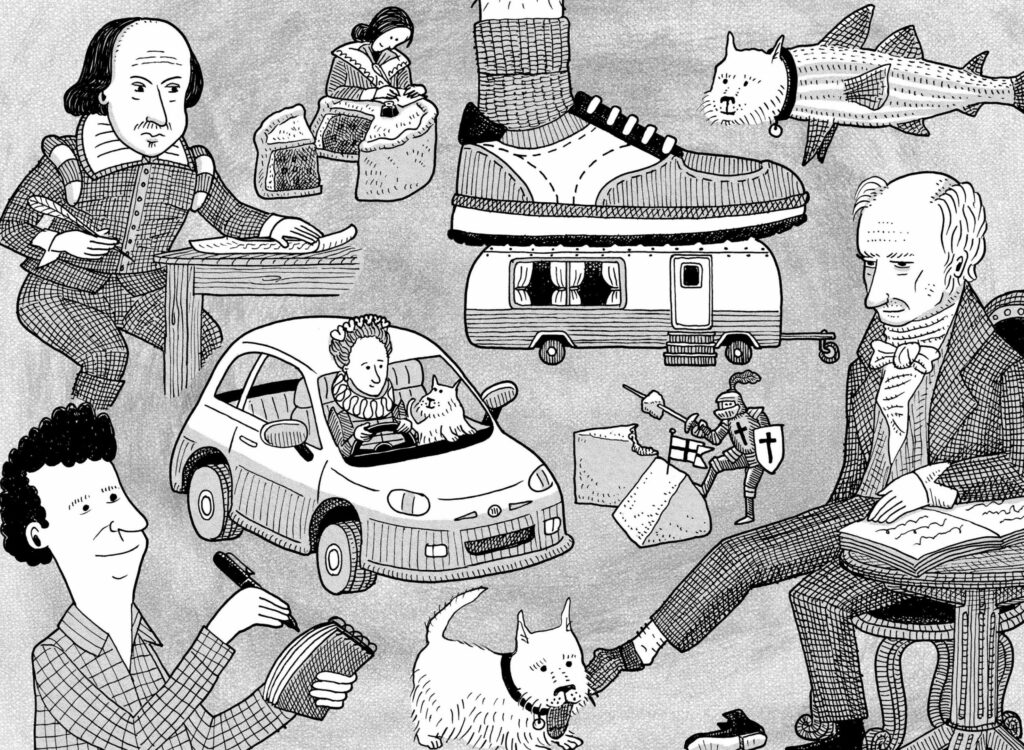

Onward again to a well-trodden literary landscape.

Tom Chitty

But the times, of course, have changed, and the last few years have hardly made for a good environment for gallivanting. Britain is going through a tough spot: stagnant wages, soaring energy prices, inflation in the double digits. It seems almost ludicrous now to picture Bryson making landfall in Dover in 1973 and ordering a full English fry-up, plus two cups of tea, for 22 pence. Meanwhile, Brexit continues to constrict trade prospects and ideologies alike. The governing Tory party has been blazing through subpar prime ministers like Tinder dates in a system that can be described only as worst past the post. And the longest-reigning monarch — in whom even the most opposed to the institution could find something to admire — has died.

Cautiously, I returned to my copy of Notes from a Small Island, wondering if the pin of reality would burst the bubble of fondness. Not really. It’s Bill bloody Bryson, after all. Yes, some of his observations have grown a little dusty. And yes, he is constantly pursuing the next one-liner, though there is joy to be found in his journey to them. But what shines through most of all is how much Bryson cares for the place where he has spent the majority of his adult life: his enduring interest in the history, that inquisitive, mischievous spark. What more is there to say?

Enter Lesley Choyce with his contribution to the British travel writing canon: a dog.

Much like the virus that lingers on in our lives, the hint of taboo around travelling for pleasure shows no sign of going away. Any venture across the ocean is now inevitably tinged with threats to health, savings, and the atmosphere that ensures the well-being of our planet. To read, then, of gadding about for gadding’s sake isn’t quite as inspiring as it may once have been. Increasingly, it’s jarring to encounter a narrative so unencumbered, either physically or philosophically, by the weight of the world.

Was this book a casualty of the pandemic? Was its publication pushed back and back, until the darker days had cleared and the skies were once again checkered with vapour trails? Who knows? Readers certainly don’t, even though Choyce packs in a prologue and an introduction that meander through his goals: namely, to have an adventure, write an entertaining account, bring the dog for fun, and take in a scrap of history here (“but no footnotes”), an ancestral connection and a literary figure there. The only leg of his itinerary he leaves out is the four-year interval between when he set off and when the chronicle of his travels was released in print.

It was back in June 2018 that Choyce and his wife, Linda, put their home in Lawrencetown Beach, Nova Scotia, in the rear-view mirror and headed across the Atlantic with their West Highland terrier, named Kelty. Around England with a Dog encompasses a month-long trip as well as chapters that cover previous (dogless) holidays from years before — which Choyce confidently terms “backstory” and which conveniently add a few additional locations to his illustrated map in the front. Diary-style, the narration is intended to give the effect of travelling along with the trio in their rental car (the tour was originally envisioned, more romantically, in a camper, until Choyce remembered the narrowness of British back roads). On occasion, an authorial voice speaks down from beyond their black Fiat — likely rocketing past a turnoff on the motorway — to explain a slip back in time to an earlier vacation or to try to circumvent the imagined critic’s quibbles about the extracurricular sojourns in France, Wales, and Scotland. In fact, the real criticism, at least for anyone born on British soil, is the implication of the title that England is the same as the United Kingdom or Great Britain, which doesn’t include Northern Ireland.

This type of roaming meditation is not new territory for Choyce. He has published several books of memoir-cum-travel, mainly centred on the Nova Scotia coast and surfing, a lifelong passion. But why he has chosen to stray further afield with his latest work — aside from the fact that he has already written over a hundred titles (his author bios maintain a constant tally) and is possibly running low on subject matter — isn’t always clear. Then again, Choyce’s overall purpose here isn’t clear either, other than his stated aim to pursue another volume, a motive that, incidentally, somewhat deflates the tires of a character-building journey of discovery.

As it happens, there is some distance between the jolly old England that Choyce envisions and the place that he actually encounters. Towns assumed to be picturesque little hamlets, or those picked for their snickerworthy names, are less whimsical and more congested with traffic and tourists than expected. Upsets to the bucolic idyll — shopping centres, cities, airports — are disapproved of, while, at the same time, the state of modern conveniences is bemoaned (central heating and hot water are hot topics). Cheery, eccentric locals who throw open their arms and their pub doors to a couple of outsiders and their friendly Westie turn out to be rather dispirited by the process of pulling out of the European Union. “We’d hear far more than our share of stories about Brexit,” Choyce complains. He then proceeds to do his best to avoid the issue that was, at the time (two years after the referendum), defining and dividing the kingdom. Less about those cultural identity struggles, if you please. Where is that stiff upper lip?

Diverging roads lay before the author: one the enlightening odyssey of his imagining and the other, for all intents and purposes, a holiday. Lofty plans to make “as many literary connections as humanly possible” soon feel a bit too much like homework. Only Wordsworth, particularly a display of his socks at Dove Cottage, receives anything close to attention. Further writerly pilgrimages are passed over with excuses of too many miles to cover and not enough time or, as appears often to be the case, not enough interest. Because the exploits Choyce would really like to write about are surfing an artificial wave in Wales — his most enthusiastic and authentic passages — and a dumpster-diving escapade from which he walks away with a pair of flashy new running shoes. Once or twice, he frets about the shortage of spiritually enriching content; then he moves on. He decides instead to make a quick detour to Catsfield . . . purely so that he can say, “We’re driving our dog to Catsfield.” Has he taken the wrong forking path?

The dog in question does little to help set them on the right trail. Despite the owner’s insistence that Kelty would sniff out interesting finds, most of the country’s castles and manor houses turn their noses up at four-legged friends. So man and beast are forced to circle the grounds, as one grumbles about the entrance fee while the other enjoys the landscaping; in the meantime, Linda waves down at them from a fourteenth-century turret. Supermarkets are equally pet unfriendly, which leads to paragraphs devoted to the parking lots of Tesco, Morrisons, and Marks & Spencer. Britain’s smallest pub, the Nutshell in Bury St Edmunds, lives up to its name and has no room for a thirsty writer and his lovable hook. “The only real problem we were encountering,” Choyce admits, “was that sometimes we wanted to do a thing or two without the dog.” They end up enlisting the help of sitters.

We hit more bumps in the road when Choyce attempts to trace his roots, seemingly another objective of the trip. His forebears hailed from the village of Sibson —“Sibson did not sound particularly exciting”— in Leicestershire. There are also a couple of more distant, more literary offshoots (a First World War poet, who was once semi-popular, and a close friend and correspondent of Beatrix Potter) that the current literary Choyce is only semi-keen on exploring. But graveyards reveal no tombstones bearing the family name, and villages offer few clues about their former residents. The air bases where the author’s father was stationed during the Second World War either have vanished without a trace or are fully operational and do not take kindly to requests to take a look around. Entries from his dad’s journal crop up now and then —“We stayed in a lodge in the country one nite & had fresh trout for breakfast”— though they provide little in the way of deeper insights. The most striking revelation is how closely these lines resemble the log Linda keeps of the more recent sortie: “Walked path back from town. Cod for dinner.” When she asks her husband what he is looking for, he isn’t sure. “Some kind of connection, I suppose.” He doesn’t dwell here long. Where should he turn next? A joke about the Cock Inn.

What’s an author to do when all he wants is to be waggish? When these relics of the past keep getting in the way? From the get-go, Choyce warns us that he is “not really much of a researcher or historian”; that he is on a research trip to discover “the less obvious truths” of an isle with a rich yet complicated history is neither here nor there. But this casual disregard doesn’t keep him from liberally proffering his two pence. At one particularly low point, a dashed-off outline of the Wars of the Roses, a series of fifteenth-century battles for the throne between houses York and Lancaster, goes so far off the scholarly course that teachers across the country should be writing in with a strict “See me.” Despite our guide’s assurances that he has read lengthy explanations on the matter, it becomes, in this telling, the singular “War of the Roses,” perhaps because multiple conflicts sound too much like hard work. But then, Choyce is, by his own admission, just a guy with his feet up — in looted fancy sneakers. He suggests readers should pay a visit to their local library if they care to learn more.

Part of the problem is that the footsteps he is most determined to follow in are those of the capering and curmudgeonly travelogues that have paved the way for this misadventure. The likes of Bryson, Paul Theroux, and the British comedian Tony Hawks, who romped Round Ireland with a Fridge in 1998, made it look so appealing: turn up to a euphonious village in order to be a mixture of bemused, amused, and bad-tempered. Indeed, a few points from Choyce’s effort appear to be plotted straight from the Notes from a Small Island road map. Consider caravans — scourge of the North American rambler. Bryson: “It seemed an odd type of holiday option to me, the idea of sleeping in a tin box in a lonesome field miles from anywhere in a climate like Britain’s.” Choyce: “It’s just that those multitudes of aluminum boxes by the water can’t help but detract from the natural beauty.” The former sniffs at “English people in shell suits,” the latter at “snot-nosed British wannabe skinhead children.” And where could those children be found? In a caravan park, of course. One might be fooled into thinking that no time had passed at all.

Time has passed, though, and even more of it since Choyce recorded those remarks. Pandemic years must be like dog years, because certain scenarios in his book are so far removed from current concerns as to be rendered unintentionally humorous. For instance, the sympathy felt for the nation’s statues and their “hard life” when “people and creatures can do them disservice at any time of day.” Choyce is referring to pigeon droppings and the occasional traffic cone placed on a bronze head, not the later trials that would befall some of these figures. Along a similar vein, an ongoing jest about a grudge against J. K. Rowling (after her West Highland terrier is named the cutest in the country) has gained an additional edge in the intervening years: there might be a few more grievances to add to that list now. Subsequent developments put a bit of a damper on a gag made during a tour of Canterbury Cathedral: “There are tombs inside with the remains of Henry IV and someone known as the Black Prince (possibly a Harry Potter character?).” Are we there yet?

After many miles, many pages, and too many dodgy punchlines that pit imperialism against clichéd character traits, we end up right back where we started, with Choyce comfortably settled again in Lawrencetown Beach. It is before dawn, and he is sat rocking one of the new twin granddaughters whose birth had been calling him home; Kelty is curled up somewhere nearby. The trips around Britain, sometimes with and sometimes without a dog, the toes dipped into the tepid waters of history, and the moment when he was finally reunited with the great poet’s socks, years after he first set eyes on them, only to arrive at the reflection that he is glad they are still there, have all become backstory. And if this jaunt has proved anything, it is that Choyce is not particularly interested in looking back.

“We really should have lingered longer” is the refrain that comes to define this month spent chasing his tail. Too often the troupe is ushered back into the trusty Fiat to pursue the next stop on this relentless drive for diverting content. Personal touch points flash by like blurry bits of scenery glimpsed out of a car window: the cancer diagnosis that first brought the couple to British shores early on in their mid-life relationship; the questions of his own literary mortality that are periodically voiced yet never unpacked; the fact that his daughter Pamela is adopted and that her and her children’s bloodline is Acadian, and how this ancestry intersects with the thread that connects him to the great-great-great-great-grandfather from Sibson.

Criss-crossing routes head toward meaning but never quite get there. Much is missed along the way. There is no consideration of the symmetry between a father’s experiences during the war that brought about the integration of Europe and the son’s return to the country during its withdrawal. There is no outsider’s penetrating and unflinching gaze at a nation that can sometimes feel as if it has more past than future. There is no genuine engagement with the various people he must have met on those countless dog walks. There is no dive into the wisdom of the ages to gain new perspective on an uncertain present. No new ground is broken in an already overcrowded field. There is not even a sense of boundless curiosity for every precious little detail in this remarkable world. Choyce might as well have gone around Nova Scotia with his Westie. Or his backyard.

Rose Hendrie is working on a novel.

Related Letters and Responses

Pam Kapelos Charlottesville, Virginia

Joel Henderson Gatineau, Quebec