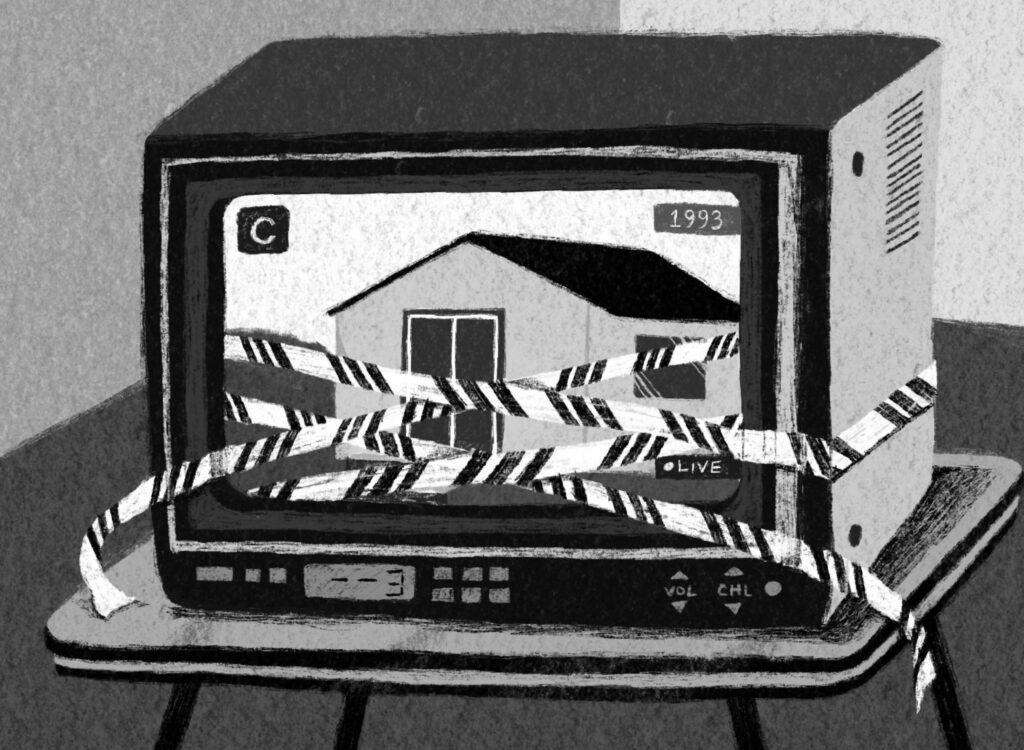

The 30-30 Winchester rifle Laurel Long held in her hands belonged to her father before he died. When she fired the gun in the kitchen of her family cabin one night in 1993, she was aiming at Rick, her mother’s violent boyfriend. At fourteen, Laurel was only trying to save Maxine’s life, and she did; Maxine recovered from Rick’s abuse at a local hospital where, months later, she gave birth to his daughter, Braya.

The action of Shelly Kawaja’s first novel, The Raw Light of Morning, takes place along the west coast of Newfoundland, an island she calls “as harsh as it is kind.” Following Braya’s birth, Laurel’s family relocates to the nearby town of Stephenville, where they rent an affordable housing unit in a ten-plex nicknamed “the Crown.” Laurel offers two pieces of information about her new home: first, that everyone “knew that living in the Crown meant being on welfare”; second, that “Stephenville’s claim to fame,” at least according to her stoner buddies, was “having the most bars per capita in North America.” Such stark pronouncements prepare readers for the rest of this Bildungsroman as it follows Laurel through her substance-addled high school years and into her first, uncertain semester at Memorial University’s satellite campus in Corner Brook.* The novel’s design is a solid one, sketching the delicate, frequently depressing realities that succeed intergenerational histories of violence and poverty.

Kawaja’s prose is plain-spoken and sturdy. Occasionally, her tendency to split sentences courts clunkiness: “Two-year-old Braya toddled around the coffee table. Her chubby fingers clamping the edge as she moved in an oval.” Generally, though, such terse language lends itself well to illustrating the gritty eccentricities of Laurel’s experience. And the author pays striking attention to the peculiarities of place, like the “flecks of nail polish . . . embedded in the woodgrain” of a tabletop, or the way the “racket of the range hood fan,” in Maxine’s kitchen at the Crown, “increased whenever the wind gusted and sucked air through the building’s vents.”

Still, other elements of the book’s construction feel slightly shoddy. While Kawaja renders physical space in finely calibrated, cinematic detail, she holds Laurel, her friends, and her family just out of focus. As far as we can tell, the protagonist approaches decisions with opaque indifference. Following her school librarian’s suggestion, she pursues university admission dispassionately, just as she mechanically burns through Du Maurier cigarettes and knocks back Molson XXXs in her basement each night, simply because her peers do. For a character with no apparent interior drive, Laurel’s success in extracting herself from her convoluted and challenging home situation seems implausible.

To save her mother’s life, a young girl fired her father’s gun.

Nicole Iu

Some of the novel’s shortcomings stem from how Kawaja handles temporality. The story unfolds in five sections, like movie scenes strung together by poorly timed jump-cuts. On one page, Laurel has just finished grade 10 and is applying for a part-time job at the Stephenville Foodland to help fund her studies; two short chapters later, a couple of years have passed and she is sitting in the phone booth of her residence building. Of course, such a technique can be made to work. But the sacrifice of continuous time — which here equates to an elision of gradual growth — feels ill-suited to a narrative concerned with aftermath and recovery. Because so much of Laurel’s healing happens off-page, many of her eventual triumphs seem unearned or premature.

Other elements also feel rushed. Maxine reads as frustratingly two-dimensional, fulfilling the cliché criteria for an absentee mother figure (late nights, lost jobs, new boyfriends). Laurel’s interest in reading is tucked in like an afterthought, presumably intended to explain her relative academic success. And Kawaja relies on dialogue for too much moral heavy lifting. Laurel’s best friend, Horsey, in a stilted exchange about Braya, declares, “You need to love the dark parts too, Laurel. You need to love the dark parts most of all.” In effect, Horsey echoes her own mother, who had earlier offered this wisdom: “Sometimes, the strongest, most extraordinary things grow in the hardest places.” It’s important, she goes on, to “hold on to that. Hold on to that as tight as you can.”

Most disappointingly, the book misses an opportunity to meaningfully engage with women’s collective healing. For every whirlwind, shouted interaction between Laurel and Maxine, we get page after page devoted to Laurel’s sexually charged friendship with the drug dealer Brax. Indeed, the protagonist’s final reconciliation with her family and her past is largely facilitated by her slow-mounting, lukewarm romance with a former neighbour, Jimmy — a narrative decision that seems at odds with the novel’s other depictions of female strength and independence.

The book’s uneven construction leaves readers hot and cold and, in many respects, wondering. What was it like for Laurel to grow up beside Braya, whose father she killed? What was said in Laurel’s first, second, and third conversations with Maxine after the pivotal event? What are we to make of Maxine’s own mother and grandmother, whose depictions in the novel seem half-hearted, their implications undigested? Above all, we are left yearning to dwell a little longer in these meticulously constructed settings and to understand the pain, confusion, and reconciliation involved in claiming a space — nail polish residue, loud fans, and all — as home.

* The print version of this review incorrectly stated “Memorial University in St. John’s.” The magazine regrets the error.

Ellie Eberlee divides her time between Toronto and New York.