All Second World War stories of deportation and privation, imprisonment and slave labour, are, in a calamitous way, the same, which is why Hannah Arendt spoke of the banality of evil long after the guns were silenced and the prisoner trains stopped running. Yet all stories of mass transport are also different — as different as the circumstances, the identity of the innocent victims, and their sad, almost always tragic destinies. The journey detailed in Wanda’s War is itself singular, from its horrifying beginning to its redemptive end, from the way it was uncovered to the way it is conveyed. Indeed, Marsha Faubert offers readers a tale of determined excavation and reconstruction: her quest to discover her in-laws’ untold past is an extraordinary undertaking given that the couple led a life of near-miraculous endurance and incalculable loss, followed by the immeasurable luck of finding their feet far from the charnel house of Europe, far from the caprice of tyrants, far from the ceaseless waves of clashing ideologies and remorseless violence.

The lives of Wanda Gizmunt and Casey Surdykowski are not, in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s phrase, twice-told tales but rather half-told ones — tales that almost were not told at all, which in a way is the whole point of this book. If the North Americans who fought to liberate Europe and to free the prisoners of the camps were the Greatest Generation, then the hostages of the continent’s dictators were the Silent Generation. They seldom shared their stories, perhaps because their accounts were, in a word overused in the decades that followed, incredible — literally beyond belief, especially in North America, history’s temperate zone in the years stretching from 1939 to 1945.

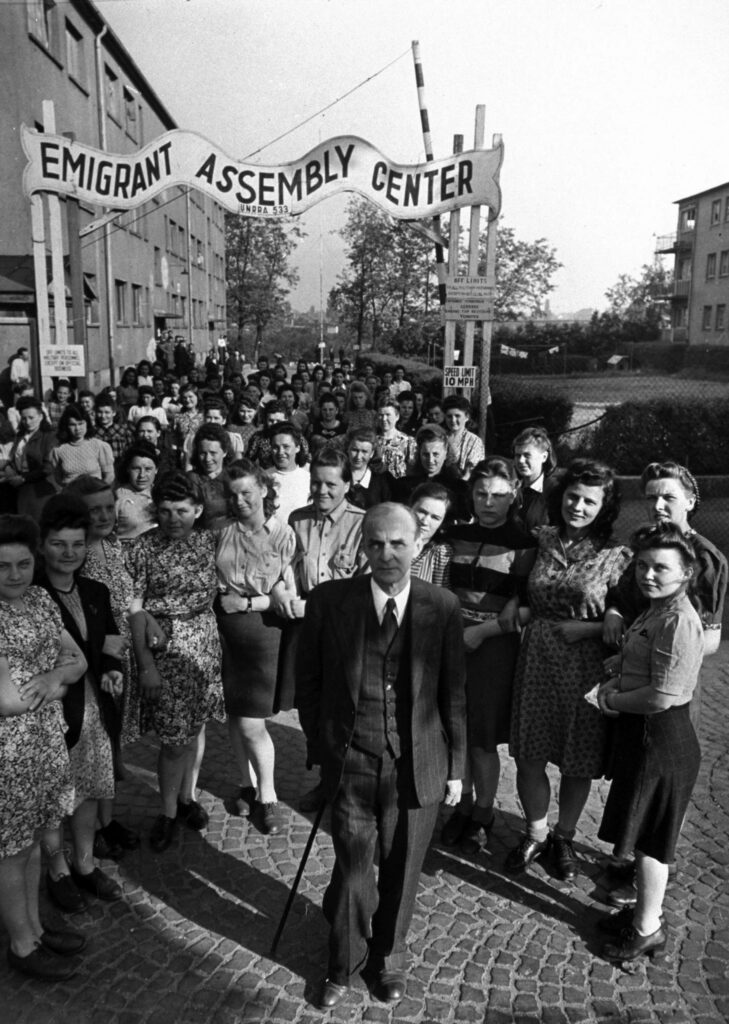

Among Ludger Dionne’s recruits to Canada.

Walter Sanders; The LIFE Picture Collection; Shutterstock

It remained to Faubert, a seasoned lawyer in Toronto, to uncover the courageous survival that her in-laws all but suppressed. “I began to understand that there was tragedy for them not just in their experiences but also in the fact that such a profound part of their history was invisible to their children,” she writes. “While their silence may have served a purpose for them, the memory of their struggle deserved its own witness.” Thus a daughter-in-law as curator of family history, a litigator as witness, and an astonishing yet uplifting addition to the great body of literature of the Second World War.

Faubert went back to a time of forced movements, often from the camps of Nazi Germany to grim satellite states in Soviet Russia: colder, more remote, even more desolate. Those deportations led to desperation and, in many cases, to starvation. They carried off the unsuspecting to unknown destinations hundreds, even thousands of kilometres away, sapping their strength, testing their character, threatening their survival. Many perished along the way, even more at journey’s end, hardship their daily diet, fear in the air they breathed. As young people, Wanda, who died in 2003, and Casey, who died in 1988, struggled amid those great waves of migration, buoyant figures in a tsunami, eventually finding the strength, maybe the unbridled stubbornness not to drown in it all, to drift finally ashore in Canada.

This family’s tragedy began after the Soviet Union joined Germany in invading Poland. Wanda, in school, was forced to learn Russian. An uncle was killed. Amid arrests, roundups, repression of Jews, enslavement, brutal murders, Casey was confined in a cattle car that carried him eastward — cold, hungry, frightened — to a destination that even today is isolated, forbidding, and freezing, covered by impenetrable forests and with steppes stretching to the far horizon. In that settlement of despair, endless hunger seemed more horrible than inevitable death. But he didn’t die there; he prevailed and fought, with Polish forces, at the storied battle at Monte Cassino in Italy in 1944.

“It is not surprising that Casey never spoke of this time to his children. Not just because he was a quiet introvert; how could he have explained such a world?” Faubert writes. “It is easy to understand why someone would refuse to awaken the memory of that time, only to share it with children living the relatively soft life of boys in mid-century Canada, who would never be able to comprehend what had happened to their father.”

The ability — or inability — to comprehend what happened is a consistent theme throughout Wanda’s War, studded with such words and phrases as “likely,” “may have been,” “probably,” and “the most I can say is.” When describing how Nazi troops looted her future mother-in-law’s village, for example, Faubert writes, “Wanda’s family of women and three children, two of them girls, must have felt especially vulnerable.” Ordinarily, this type of speculative language in a work of history — the imagining of thoughts, feelings, conversations, observations — might be regarded with skepticism. In this case, however, it might be excused.

Because records of the family’s movements are scarce, Faubert filled in the holes, many of them gaping, with accounts of developments and events that offer hints, if not hard evidence, of her in-laws’ experiences. (Even so, she mined remarkable information from archives and other sources along the way.) Despite the fact that in many cases she had to write around some elements of Wanda’s passage, Faubert nonetheless presents a readable, trustworthy, and heart-wrenching narrative of how Nazi Germany, slave labour, and Canadian immigration policies operated.

As she describes the Nazi war machine that enslaved so many foreign workers, Faubert artfully draws upon spare but telling details. “The campaign began with the ‘recruitment’ of eighteen- to twenty-one-year-olds,” she writes. “Gradually, the target ages were lowered, and by the end, entire families — including Wanda’s — were deported to Germany.” Such passages give us the haunting context if not the particulars.

Wanda’s War comes a year after Michael Frank’s One Hundred Saturdays, the remarkable odyssey of Stella Levi, ripped from the island of Rhodes and sent to Auschwitz in the longest deportation of the war. Again: the same story, only different. Although Faubert’s father-in-law, Casey, plays a role in these pages, they’re really about Wanda. As such, it is part of a spate of Second World War books that focus on women, sometimes in underground combat, sometimes in espionage, sometimes as brave survivors.

Wanda always associated home with Poland, which became part of Soviet Byelorussia. “When the Soviets occupied Poland’s eastern borderlands in 1939,” Faubert writes, “their campaign of Sovietization included conferring citizenship on the inhabitants, whether they agreed or not.” Four years later, she was sent to Germany, where she was one of 13.5 million who were conscripted for slave labour and, later, one of 11 million freed after the Nazi defeat. Wanda slept in barracks, made parts for train repairs, lived in a barn, moved from one place to another after liberation, and arrived in a displaced-persons camp. At the age of twenty, she went to a gimnazjum, or high school. “For a brief time,” Faubert writes, “she had the ordinary pleasures of youth: the peace of the classroom, the company of her fellow students, and the challenge of learning.”

Canada may have considered itself an open society in the postwar period, but it was no more open to accepting displaced persons after the conflict than it had been to welcoming the Jews who fled Nazi Germany before it (an inglorious story told by Irving Abella and Harold Troper in their influential None Is Too Many). Because shipping capacity was limited, demobilizing soldiers was seen as more important than settling refugees. And given economic distress, why tempt higher unemployment with a flood of new workers?

There was also a general weariness about the world’s woes — and some reluctance to import reminders of recent strife in Europe. Immigration had been severely restricted since 1931, and government officials generally regarded refugees, in wording employed by the poet Emma Lazarus for an entirely different purpose, as “wretched refuse” from distant “teeming shores.” Why deposit that detritus here?

It wasn’t until a year after VE Day that Ottawa allowed Canadians to sponsor close European relatives as well as more distant relatives under sixteen who had been orphaned. Wanda and Casey emigrated separately under peculiar arrangements, coming to Canada as “unfree but necessary labourers in the first stage of a post-war immigration wave that would fuel economic boom in the decades to come.” Even then, there was resistance. Jack Blackmore, a member of Parliament for Lethbridge, Alberta, asked in a speech of special dishonour, “Are they Protestant, atheistic, Roman Catholic, or Judaistic?” And then he added, with perhaps even more disgrace, “I believe every member of this House realizes that any preponderance of any one of these among new immigrants would certainly be creating a new handicap to large bodies of the Canadian people.”

But vast agricultural lands provided an opening for would-be farm workers, and the seeds of Canada’s postwar expansion were planted when a small cohort of them arrived. Casey followed them in 1947. Wanda’s opening came that same year, after the textile manufacturer and MP Ludger Dionne, in desperate need of employees, was granted access to an emigrant assembly centre in Germany. She and her companions signed contracts that obligated them to work for minimum wage for two years at the Dionne Spinning Mills, in Saint-Georges West, Quebec. Their flight stopped in Bangor, Maine, before they encountered a new country and a different type of privation: a labour strike and yet another move, to Kitchener, Ontario. Leaving Quebec was “an act of faith,” Faubert explains, “a leap into the unknown, guided by the confidence that comes with having survived the worst that strangers could inflict on them.”

Not far from Kitchener was Stratford, where Casey had found a job, first as a mechanic and later in the B. F. Goodrich factory, building tires. And there, at a dance at the Polish church, he met Wanda. The two had much in common. “They understood each other’s experiences and past lives without explanation or confusion,” Faubert writes. “What better way to settle into a new world than with someone who shared one’s roots and understood one’s past, someone who spoke the same language, whose culture, food, and religion were familiar?” They married in 1951 and had two sons, George and Chris.

In an essay she dictated to George (the author’s husband) as part of her application for the compensation that Germany eventually offered to those who suffered the Nazis’ cruelty, Wanda recalled her ordeal in a straightforward fashion:

We lived in a barracks behind barbed wire. Every morning the guards took us to the work. We worked from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., I think. There were armed guards in the factory watching us while we worked. In the morning before work they gave us one slice of bread and black coffee. . . . We were not ever allowed to go outside for any reason except to go to work. There were armed guards outside the barracks. We worked seven days a week. The guards would beat at us for no reason. The barracks were filthy and full of lice and bedbugs.

In May 2002, she was awarded roughly $1,600: a paltry sum and Germany’s “voluntary humanitarian indemnification.”

In some ways, Wanda’s reticence about her experience was a greater reward, at least in the view of her daughter-in-law, who came to understand the depth in those silences even as she viewed them as a barrier to understanding this resilient woman’s world. And so, in the very last paragraph of this captivating narrative, Faubert reflects on the conversations she never had with her mother-in-law, the questions she never asked, the empty holes in the story she will never completely fill. “Silence was her right,” Faubert acknowledges at the end of her search. “Who is to say that the burial of her memories, the simple life in a safe space, wasn’t justice for her?”

Who indeed? Who, in the end, would deny Wanda Gizmunt the justice she sought, and maybe found?

David Marks Shribman teaches in the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University. He won a Pulitzer Prize for beat reporting in 1995.