I am not sure when my personal habit of Woke started, though I do know it comes from a time in my life when the bathroom was not entirely my own. I’m equally uncertain why I called it Woke in the first place, though claiming that I called it anything is a bit of an exaggeration. As best I remember, the word just popped into my head at the sink one morning in the mid-1970s when I decided hot water wasn’t worth the wait.

Woke wasn’t a word that I used, exactly. I never said it. Never wrote it. Hardly even thought it. I acknowledged it but only with a blank, unspoken salutation — as if to a familiar landmark passed daily on a routine commute.

Three splashes of water that absolutely must be cold.

Tom Chitty

I’m not actually sure I even thought of it as a word. Its meaning wasn’t exactly concrete. I never pictured it in Times New Roman. I never imagined it pronounced by Colin Firth. It couldn’t form a clue on Jeopardy! that anybody (other than me) might solve in the form of a question. My Woke existed in some protolingual filing system in my brain. It was too innocuous an activity to be much of a verb. Too formless for a noun. Too amorphous to be a helpful adjective or adverb.

Its noncommittal independence appealed to me, I suppose. As words go it was one letter short of a participle, but no matter. I was looking for something that was sort of a subject, sort of a predicate, and that needed a grammatically non-specific designation. But what kind of word was my Woke? I don’t know. Ask that guy Fowler. As I say, it just popped into my head one morning at the bathroom sink. Faucet, hands, water, face. That was the brief but complete sentence I needed to compose. Given the simplicity of the task, I thought it best to use a word with one syllable, no modifiers, and without tertiary or secondary or even primary meanings. Woke fit the bill. It was nothing if not adaptable.

Woke’s disinclination to be defined allows it to be whatever anybody wants it to be. This has rhetorical advantages — especially if you are not Woke. And won’t be. Ever. You’ll stick with the pronouns God gave you, thank you very much. And if fifteen-minute cities were meant to be, Tim Hortons wouldn’t be on the highway, would it? Being opposed to Woke, when Woke can mean anything from riding a bicycle to controlling the global economy, gives everybody and their uncle something to talk about. All the time. As you may have noticed.

My Woke had nothing to do with any of this. The only claim that my Woke had to being a word was that it was a private label for something I did (and still do) every morning.

A brisk approach to bathroom deployment was taught to me at an early age by my father, who wanted to know if I planned on being in there all day. Speed and efficiency are characteristics to be prized among those who share facilities. If you want to be unpopular — in a rooming house, a B & B, or a family — take a long morning shower.

My guess is that it was during the fast-teeth-brushing period of my childhood, or the hasty Brylcreem application of my adolescence, or perhaps during the slightly later but no less hurried Gillette Foamy stage of my undergraduate years that I stripped things down to essentials. When a knock on the bathroom door could come at any moment, I learned to move nimbly through the stations of the plumbing.

The daily challenge was this: how to spend as little time as possible in the communal loo while still accomplishing the reasons for being there. If a bubble bath, exfoliation, and toenail clipping constituted the slow and selfish approach to the sharing of indoor conveniences, and if being washed by the rain in the backyard was the saintly opposite, what compromise would be popular with my family or housemates without leaving me looking as if I were fed by ravens? It was a question to which I devoted special consideration as a young co-signer of a lease for student digs with shared kitchen, one bathroom, limited hot water, and parking for seven bicycles on the porch. And what I settled on over time was three splashes of water in my face, over the sink, with the same steady count every morning: A-one. And a-two. And a-three. Like Lawrence Welk. That’s what I called Woke.

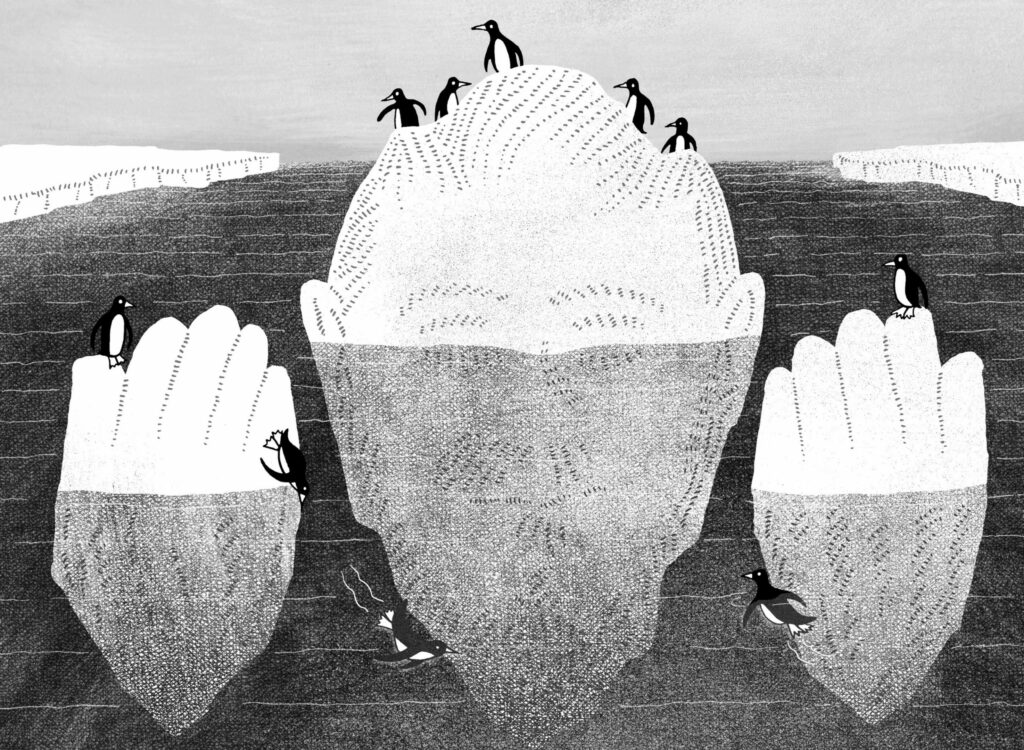

If Woke entered my consciousness as an actual word in those happy salad days before Marjorie Taylor Greene found Twitter, it was only because there were occasions when I found myself at my desk, with my coffee hot and my typewriter loaded, and I realized that for some reason I’d forgotten the splashes of water. Maybe I’d had a shower that morning. Maybe a sauna. Maybe a loofah scrub, some self-flagellation with willow branches, or a plunge among the icebergs. Maybe yoga, calisthenics, a massage, or a micro-dose of LSD. Didn’t matter. Uh-oh, I thought. Woke.

If I’d forgotten to include three cold face splashes in my morning routine, my writing day could not properly begin. That was (still is) the law. There was no debate about this. The word didn’t have to flash twice in my consciousness. Uh-oh, Woke. That’s all it took. I’d get up from my desk, walk down the hall to the bathroom, and — a-one, and a-two, and a-three — correct the situation.

Woke — my Woke — had no compositional agency. Grammatically speaking, it was what it was. There was no getting Woke. There was no being Woke. There was no Wokeness. Or Woken. Awake was too Pentecostal a term for my taste. Awaken was worse. I wasn’t going to stand in front of the mirror every morning and speak to myself like a Baptist preacher.

There was just Woke — a word that began its role in my life humbly, without metaphorical aspirations. Obviously, it had something to do with waking up and something to do with getting to work. Less obviously, with Lawrence Welk. Also, it sounded like what it was. It was a reasonable aural facsimile of the effect of having water scooped into my face.

Woke was in my private lexicon long before its current tedious vogue. And you can’t blame Woke for being tedious. A word, however well-intentioned, is bound to get irritating if the only people who ever use it are the same people who complain about it. All the time. Whatever it is.

But as far as I knew, Woke was meaningless beyond what I chose it to mean. In my ignorance, I thought of it as unclaimed, a word with no reference to anything tangible. For my purposes, it was drawn from the same self-instructional conjugation as “gargle” or “put the toilet seat down.” Woke was just what I did every morning: one of the things on my checklist of the get-in, get-out ritual of communal living.

The habit stuck (see: “Writers, superstitions of”). Even as my bathrooms became less shared in their shampoos and more ensuite in their dry towels, even as time marched on and knocks on the door became less frequent, I continued to start my working day with three double-cupped handfuls of cold (it must be cold) water. Splashed into my face, first thing. Well, almost first thing. This is as daily as coffee. Which is to say very daily.

I knew nothing about Woke’s older usage. Clued-out, middle-class, culturally disposed to clap awkwardly on the one and the three, I hadn’t yet learned that Woke was an old warning, from African American to African American: To be careful. To be on the ball. “Stay woke,” the great bluesman Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter said eighty-five years ago. “Keep their eyes open.” He was talking about his song “Scottsboro Boys,” which tells the story of nine young Black men unjustly accused of raping two white women in Alabama. To say the lyrics are cautionary is putting it mildly. You’re damn right they had to stay woke down there. “Go to Alabama and ya better watch out / The landlord’ll get ya, gonna jump and shout.”

Unaware of the word’s Jim Crow history, I settled on Woke as the unspoken term for the part of my bathroom routine that had to do with being watchful.

I’m what some people call a morning person — others, a senior citizen. That is to say, I am up early. But in my case, I always have been. My writing energy has always peaked around noon, with a slowly declining trajectory thereafter. That’s why the earlier I start, the better. But I can’t just roll out of bed and begin. There are steps of protocol, and the words that identify those steps are pretty much what you’d expect in a bathroom, in the morning. But there is a part of the procedure — the part I labelled Woke — that has less to do with personal hygiene than with getting ready to write. That’s why the water must be cold.

It’s essential to clear away the fog as much as possible. Why? Because words are tricky, that’s why. That’s why you must be on your toes. That’s why you must be alert.

Words don’t always do what you want them to. You have to be attentive to what they are saying, especially when it’s not what you expect them to say. And that’s why my Woke still happens every morning, just as it did when I couldn’t figure out who was always using my Head & Shoulders. A-one. And a-two. And a-three. I like to think it does some good.

David Macfarlane is the award-winning author of The Danger Tree and other books.