Given that the pandemic has significantly altered our daily lives, it is necessary to gather information on its effects on mental health and coping skills.

— Statistics Canada

Sometime in the spring of 2023, I received a slim brown Government of Canada envelope in the mail. My first thought was that it was an adjustment to my tax return. But then I noticed the listed agency: Statistics Canada. I opened the envelope, half pulled out the letter, scanned the top. It was a study of some kind. My household had been selected to participate in the Survey on COVID-19 and Mental Health. Great, I thought, another questionnaire. I had that week already been pestered by an online retailer wanting me to rate its performance in regard to a recent transaction (a replacement vacuum cleaner hose and a tube of age-spot remover). Then there was Airbnb, which desperately wanted me to rate the host for a property we had rented for the weekend. I actually would have reviewed the host (nice but a bit rule-obsessed) and the property (decent), except I would have had to note that if you are cheeky enough to charge $350 a night, you might want to state in advance that the lone toilet flushes into a septic system that can’t accept even a sliver of bathroom tissue. Because of this, your five hearty guests with middle-aged digestive systems (isn’t cabin appetite something?) will be forced to spend their weekend inserting soiled tissue into zip-lock baggies (not supplied) before placing said baggies into a black garbage bag.

Like almost everyone else in the post-pandemic world, I am a little grumpier than normal. So, following Thumper’s father’s advice about not saying anything if you can’t say something nice, I didn’t fill out the Airbnb review. Would I fill out the Statistics Canada survey? I looked at the letter a little closer and noticed again the phrase “mental health.” Gut reaction: definitely not. What business does the government have monitoring my mental health? Perhaps I’d be okay if my local department of health was asking, though not until they take seriously the problem of data hacking. But was my paranoia itself symptomatic of poor mental health? I walked to the bin, pulling the letter out all the way, flipping it over, searching the text for the word “mandatory,” and finding instead the world “voluntary.” That was my signal to release it into the waiting receptacle. Wait now: I quickly retrieved it, walked across the room, and placed it in the recycling bin. In St. John’s, we have a four-colour garbage collection system. Clear bags for ordinary trash (maximum of three per household per collection); blue bags for recycling (separate ones for paper products and for plastic containers, but as many as you like of each); brown paper bags for yard waste (as determined by season); and a black “privacy” bag (one per household; see zip-lock baggies above). I’m reminded of the city’s bureaucratic zeal every time I take the trash out.

About a week later, I received a second letter from Statistics Canada. I opened it and found it was the same as the first. I quickly discarded it, thinking no more about the matter until ten days later, when I received a phone call. The caller, a quiet-spoken man, identified himself as a Statistics Canada employee. He wanted to know if I had received the invitation to fill out a very important survey on mental health. I told him I had received not one but two letters. He had begun running through his script of talking points when I politely interrupted him, letting him know that I had decided not to participate. He seemed stunned. His voice shook a little with emotion as he described the value of this survey and how only one in a thousand homes had been selected. I told him that I understood, but I had decided for personal reasons not to participate. I then asked him if the survey was mandatory. He said it was not. “That’s what I thought,” I said. Silence ensued. Grabbing the opportunity, I asked if he could please take my name off his call list. Again, he seemed stunned. “You wish me to take your name off my call list? You do not wish to participate?” he asked. “Right on both counts,” I said. “I am going to hang up now. Have a pleasant day.” I always try to be nice to cold-callers. I had some crummy jobs in my youth. I knew this man was only following a script, doing his thankless job, while his superiors hid in their offices playing Bubble Shooter.

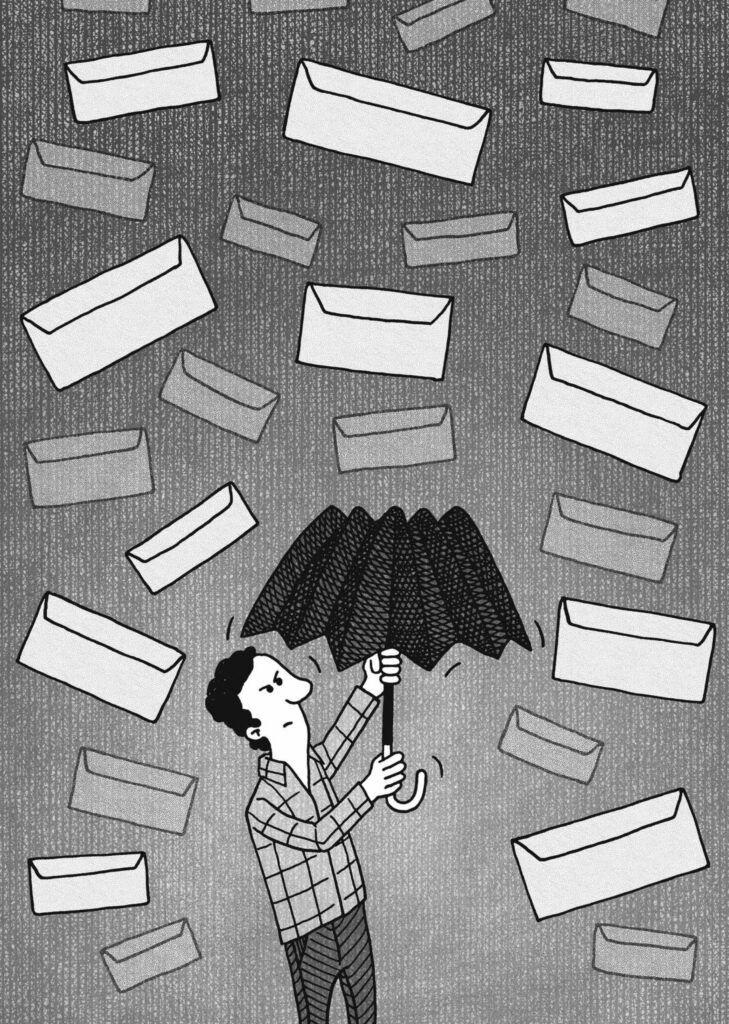

Somebody make the surveying stop!

Tom Chitty

I was in a less relaxed mood when I got a second phone call, again about a week later. I was watching a sporting event and my team, in a crucial playoff match, had just blown a two-goal lead. The caller identified herself as an employee of Statistics Canada. She wanted to know if I had received the invitation to respond to these very important questions. I repeated myself about the two letters, mentioned the previous phone solicitation, and reiterated my decision not to participate in the survey. You’ve got to be kidding me! The opposing team had just sliced through my team’s defence and almost scored. The woman began to aggressively pitch (or it sounded that way to me in my distracted state) the virtues of the survey — and perhaps I heard something in her tone that intimated it was my civic if not patriotic duty to help out in these unprecedented times. My team failed to clear, and the opposition cut through again, this time pinging a shot off the crossbar. What the hell is going on? Suddenly, I resolved that the game on TV needed my full attention if my team was to have any hope of staving off the pressure. I interrupted the woman and asked her if the survey was mandatory. “No, it is not,” she conceded after a brief pause. “In that case,” I said, “it’s my decision to not participate.” The woman immediately launched into her script again. Foul on the edge of the penalty area! I interrupted her, asking her to remove my name from the call list. She pivoted, continuing in her attempt to persuade me about the importance of my feedback. “Please take me off your call list!” I barked. Instantly, I was not proud of myself. “I can’t do that,” she said. What? The vapours were upon me. How absurd is that, my oxygen-starved brain thought. You design a survey and randomly assign it to households across the country, tell folks that participation is voluntary, then tell those who do not wish to contribute that their name can’t be removed from a call list! Unbelievable. “Please take my name off the list,” I said again, this time in more measured tones. The woman continued with her prepared remarks. “Please take my name off —” The woman now spoke over me, her voice rising in anger. “If you would just let me explain —” I didn’t want to hear her explanation, which I was sure would be just another version of the same. The opposing team had just scored for the third time. “I’m hanging up now,” I said. Afterwards, I immediately blocked the Statistics Canada number.

Believe it or not, I once worked for Statistics Canada. Back in my deeply unemployable days, I was glad of a summer job going door to door in a very poor area of town, collecting census data. The poverty I observed behind closed doors was something of a shock to me, a recent graduate with a bachelor’s in English literature and anthropology. That the census was mandatory was something that I had to explain to people, most of whom were unfailingly nice about it (and compliant with the law). A few older ones chose to point out that they were not Canadian by choice. These were pre-’49ers, born before Newfoundland voluntarily (some say there was no other option, therefore the decision was effectively mandatory) gave up its status as a dependent territory to enter Confederation. In the four weeks I spent knocking on doors in that warren of a neighbourhood, I met only one person who might have been described as difficult. She was American, middle-aged, and — judging by her hair, dress, and jewellery — a hippie, possibly one of the wave of Americans who crossed the border during the Vietnam War. Not that our exchange began with hostility; things took a bad turn only when I explained to her that filling out the long (2B) form was mandatory. She said that Ottawa was invading her privacy, which was also somehow a violation of her rights. I was taken aback by the ferocity of her rebuke. At the same time, I was impressed by the way she stood up for herself. In doing so, she offered me another view of the world that, for complicated reasons to do with my own upbringing and my insecure status as a recent immigrant, went far beyond my reach.

How times have changed, I thought, as thirty years later I reviewed my recent phone calls with the Statistics Canada representatives. I was no longer shy about questioning authority or voicing my opinions. But it wasn’t just me who had changed. The zeitgeist had changed, too. The civic spaces we share had become more contested — or at least that’s how it seemed to me. A few minutes’ reflection convinced me that the evolution of discourse is more serpentine than straight. Public engagement and debate rise and fall with the times. Just because things were quiet in the 1990s didn’t mean they always had been. One need only read reports about those volatile debates in 1949.

I didn’t so much forget about the survey as put it on the back burner. But a few weeks later, having missed a call from someone who didn’t leave a message, I checked my phone records online. Much to my surprise, I counted five attempted calls from the Statistics Canada number I had blocked. Such perseverance raised my temperature. Why was my participation so important to them? And why was it important for me to know the answer to that question? It wasn’t. I told myself to let it go. There was something about the situation, however, that made me want to resolve it. It took a third and indirect exchange with Statistics Canada before I became energized enough to do just that.

Late May brings a big birthday weekend in our house. This year, my youngest daughter turned twenty, my oldest daughter’s husband turned thirty-four, and my wife’s aunt turned eighty-plus. It’s our mini-tradition to host a dinner for all three. My wife decided to go all out and baked each of them their favourite cake. Sometime after dinner, my oldest daughter casually mentioned that she had received a phone call from Statistics Canada. She said it was about some post-pandemic health survey.

“Oh,” I said, “they are after you now. They were after me a few weeks ago.”

“No,” she replied. “They weren’t after me. They were after you.” Wait just a minute! She told me that she and her husband — their household — hadn’t been selected to participate in the survey but that Statistics Canada had called her, hoping she might persuade me to fill out the survey. Now surely this was an around-the-net, backhanded attempt to get the puck past me. It was certainly out of bounds, offside, or some other sporting metaphor for an illegal move. Full of cakes and fine wine, I found it hard to believe what I was hearing. I decided not to make an issue of it. I didn’t want to spoil what was otherwise a very nice evening.

But the next day I added things up in my mind. Statistics Canada had sent me two letters, had spoken to me twice, and had then made five subsequent attempts to reach me by phone after I told them to stop calling. Unable to get through, they had called my daughter in an attempt to leverage her influence over her dad. Really? Was I that special? Their attention didn’t make me feel special. It felt more like harassment. Finally, my pique settled on a point of language (as it often does). The good folks at Statistics Canada had somehow failed to grasp the difference between the words “mandatory” and “voluntary.” They had somehow mixed up the meaning. This was the only explanation I could muster for why they would not respect my decision to ignore their survey. I wondered if “voluntary” means something different when used in the realm of statistics. Maybe I was at fault. Maybe I had misread or misunderstood.

I did a little digging and discovered that in statistics there is something called a “voluntary response sample,” which is “made up of participants who have voluntarily chosen to participate as a part of the sample group.” Generally speaking, such participants “choose to respond to surveys because they have a strong opinion on the subject of the survey.” Maybe Statistics Canada needed my lack of enthusiasm as a counterweight? This was interesting, but it didn’t help me at all. Being an English major, I pulled up Dictionary.com: “Voluntary. Of one’s own accord or by free choice.” This confirmed my position but left me no wiser about the position of those who kept bothering me.

In the early months of COVID-19 — when we were all working from home, communicating via Zoom, and generally trying to get used to the sudden and weird turn the world had taken — I attended a virtual staff meeting. Most of the time, our in-person meetings are very relaxed, fun even, but this one (as we neared the end of two hours) took a nasty turn. Much later, as we began to navigate a partial return to the office, a co-worker and I discussed the moment and the distinctive mood that had marked the first lockdown. Her take was that the COVID-19 situation was a magnifier of sorts; it enlarged (and so distorted) everyone’s personality, both the good and the bad. After we spoke, I thought of all the public figures who had taken centre stage during the pandemic and of how I watched them struggle to communicate a clear message. One had to look no further than the prime minister: isolated at his microphone, giving his daily dispatch of care and reassurance, his voice full of empathy, his eyes shining with sincerity. Soon, however, I saw that his performances did not match up with his behaviour during the media scrums that sometimes followed. No matter how much I liked his new beard, I could not let him off the hook for his non-answers. Typically, he answered the question he did not want to answer by answering the one he did want to answer, for which he had a prepared script. Day after day, I watched him pause to recall rather than to actively think. Journalists quickly got frustrated. The PM got frustrated. Did I occasionally see him smirk? Did I imagine that his lips moving behind that mask were sometimes saying words other than those I was hearing?

Not that I mean to pick on the prime minister. His is a tough job at the best of times, and he has certainly shown that he can be a capable politician. The point I am trying to make is that the pandemic didn’t so much change discourse as bring it into a clearer focus. Doublespeak, obfuscation, and outright lies are nothing new, but what changed suddenly with the pandemic was their visibility. The public noticed. We began to wake up. We grasped that what we had come to expect from our leaders — be they in government, business, education, or any other sector — were non-answers: in other words, manipulations offered in a language that was almost always condescending. “Carewashing,” which a pair of British academics recently coined, captures the technique well: “communication strategies designed to demonstrate how ‘caring’ a corporation is in ways that commonly obscure that corporation’s actual destructive social and environmental impacts.” These days, one can easily replace the word “corporation” with “government,” “university,” “school board,” and so on. Not that the misinformation was, or is, entirely self-serving. We all seemed willing to accept this behaviour from the government as long as the economy grew and our personal livelihoods were not threatened. Suddenly, in the face of a real crisis, the official response no longer placated us. The words seemed hollow and insincere, and often on examination they proved to be just that. We sensed an agenda other than the stated one. The public reacted with disbelief and anger. The government responded by turning up the rhetoric while turning on the money taps, delivering as much as was needed for as long as was necessary.

Well, the crisis has passed for the moment, and now I find myself wondering about all the anger we directed toward pandemic-era authority. Was it fair? Would some of that anger have been more properly directed toward ourselves, for having been asleep for so long, for accepting platitudes and ideological slogans from our business and cultural leaders, for continually electing politicians who make promises we know they won’t keep? If we were to accept our portion of the blame, how might it influence our future behaviour? What are we to do with our impressions and feelings in the aftermath of COVID-19? Should we use them to fuel demands for better leadership? Do we slip back into somnolence? The problem is how to un-see what was writ large for so long. It’s hard to fall asleep while seething.

So this is where we find ourselves as we slide into the fall of 2023: I am beginning to understand better why those Statistics Canada employees irked me. The care for the health of the general population that is expressed in the preamble to their survey (including guaranteed privacy for respondent data) is called into question when the agency’s behaviour undermines its stated aims. If participation is voluntary, why harass the reluctant until they agree to participate? Somehow, in an Orwellian inversion, “voluntary” has become “mandatory.” But why? Is there a hidden agenda? Now here’s a bent thought: perhaps what Statistics Canada hopes to measure is the public tolerance for just this kind of “typical” institutional behaviour. Perhaps the survey is designed to determine just how crazy-angry the population remains. Is it a shaken government’s way of asking if it should continue to govern as it had before the pandemic?

Ten years ago, the political spectrum was relatively linear: it ran left to right. After the pandemic, there is a curious space in the centre of our politics where far right and far left are indistinguishable, at least in how they behave. The ends have bent to meet in the middle. Please, Lord, preserve me from such loonies.

It occurred to me that maybe I had missed an opportunity. I had let slip my chance to advise the government about how best to communicate with the greater population in the post-pandemic world. I might have said to them (in a version of the Newfoundland saying “Stay where you’re to till I comes where you’re at”) that if you say what you mean, we might believe what you say. How about a little honesty in this new era? How about a peck of courage? How about governing as if the goal of creating a healthier population and healthier institutions supersedes being elected for another term? How about leading by such an example?

Maybe I’m not so much angry as frustrated. Lest I be hoisted on my own petard, I decided that I would write to Statistics Canada and lodge a complaint. I would state my concerns about aggressive data collection strategies. I would ask for an explanation and an apology — not from front-line staff but from administrators. I was directed to send my comments to a generic email address. Not satisfied, I located the addresses of Canada’s chief statistician and the director general of health statistics. I sent them the same email separately, because my bureaucratic antennae told me that this way there would be less chance (statistically speaking) of one leaving it to the other one to answer.

To my great surprise, I eventually received a reply. “I apologize for the inconvenience our collection methods have caused,” it began, “and for the negative experience you had with our interviewers.” But, it went on to say, all that contact wasn’t collection methods overkill — just an attempt to raise awareness among potential respondents. Because my daughter’s private number was once associated with my address, they thought they might be able to reach me through her. Statistics Canada thanked me for my valuable feedback, which would help improve its processes — though it was left unsaid which processes might be improved or how. The letter writer ended by stating that while I would no longer be contacted for the Survey on COVID-19 and Mental Health, I might still be contacted on other matters in the future.

All in all, it was as skillful a bit of bureaucratese as I have read in some time: an apology that does not quite apologize; an explanation that does not explain; a reprieve that does not remove the possibility of future irritation. In other words, governmental business as usual.

Patrick Warner is novelist and poet in St. John’s.

Related Letters and Responses

Patrick Warner St. John’s

Joel Henderson Gatineau, Quebec