Vincent Lam was just a few years out of his residency and working as an emergency room doctor when SARS hit Toronto in 2003. That experience informed Bloodletting & Miraculous Cures, which follows four characters as they scramble through medical school and begin their careers right before the outbreak. (It won the Giller Prize in 2006.) More recently, Lam has focused his practice on addiction treatment; since 2016, he has helmed the Coderix Medical Clinic, not far from Moss Park in downtown Toronto. And that work most certainly informs On the Ravine, in which Lam reprises two characters from his debut: Dr. Chen and the former Dr. Fitzgerald.

Now two decades out of medical school, Chen runs the Swan Clinic in Toronto’s Kensington Market neighbourhood, where he treats a diverse range of patients with an abundance of compassion and generosity. In his off-hours, he navigates the city on his bike, distributing safe injection kits. Chen once thought heroin was the “worst-case scenario” when it came to addiction. But now he is “more likely to alert patients that their fentanyl had other drugs in it — carfentanil, etizolam, crystal.”

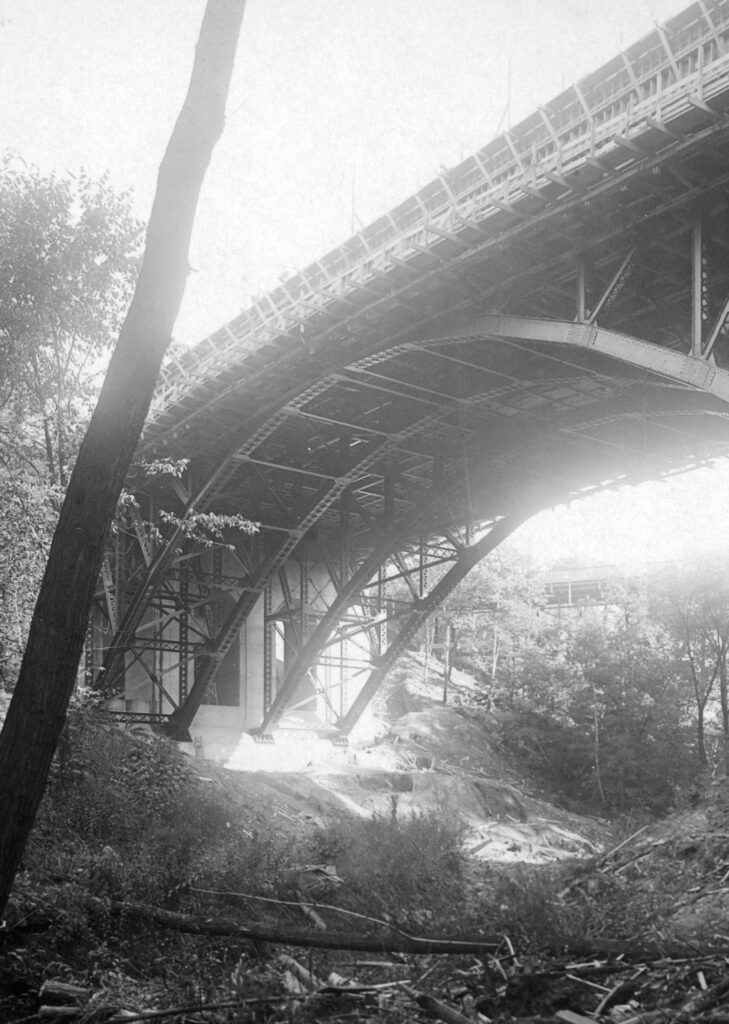

Fitzgerald’s life has shaped up in a markedly different fashion. After a highly publicized trial concluded that he had been recklessly prescribing opioids, he gained the moniker “the Dealing Doctor” and lost his medical licence. He now drinks heavily and runs a shooting gallery in his dilapidated Rosedale mansion, where he offers clients a place to safely use the “pharmaceutical-grade stuff” that he also deals (provided they hike up from the steep ravine below and enter through the back).

Despite it all, Chen and Fitzgerald have managed to stay close. Early in their careers, they co-founded Varitas, a pharmaceutical trials company. Now Chen oversees the trials, which are stocked with participants from among Fitzgerald’s clientele; the Dealing Doctor is rewarded handsomely for the referrals. Chen’s involvement with the pharmaceutical industry is, of course, fraught. While he believes that “pharma got paid to light the fire, and now they want to get paid to put it out,” he is nevertheless willing to do whatever it takes to help alleviate his patients’ suffering. The interactions between diligent Chen and permissive Fitzgerald are at once quietly funny and touching in their strangeness.

In the steep ravine below.

City of Toronto Archives; Fonds 200, Series 372

On the Ravine begins as Varitas has received the backing of a sponsor, Omega, in order to test a potential silver-bullet addiction treatment. As the preparations for the clinical trials commence, Chen finds himself romantically pursued by Bella, an Omega project manager who has “the look of an advertisement model on the inside of a magazine cover.” Although the doctor is interested in Bella, he’s more occupied with thoughts of an unnamed medical student who once trained with him at the Swan.

Between chapters, Lam inserts letters that Chen writes to the former student, reflecting on their time together and ruminating on the practice of addiction medicine. “The diagnosis of a substance use disorder is made by measuring displacement, loss,” he writes. “Have enough stones dropped into the bucket of water that it has begun to run over, soak the carpet, wet the feet? But what if the water evaporates? Then what to look for?”

One day, Chen is visited by a new patient at the Swan. He recognizes the young woman as Claire de Lune, the violinist who performs every Thursday night at a restaurant near his apartment. Chen used to take the medical student to those weekly performances, and Claire, recognizing him too, wonders why he has been coming alone recently. From the outset, Chen’s treatment for Claire is complicated by his admiration for her talent. “You play so well despite the pain, despite the drugs. Imagine if we can help you,” he resists telling her, “the music you would make.” While Chen’s ability to treat Claire subjectively is prejudiced, he is nonetheless correct that her music is inextricably bound up with her addiction. As she shares her story — that of a promising young artist, of shoulder injury, of taking more and more opioids to play through the pain, of full-fledged addiction — Chen listens with the attention that he once gave to her music.

Over the course of the novel, Lam charts Claire’s attempts to get clean as the prospects of her career continue to grow dimmer. When Claire’s sister, Molly, arrives in town, the two begin to use with total abandon. In the wrenching scenes that follow, the sisters pool money to score and help each other fix, though often not at Fitzgerald’s house, where “there would have been someone with an antidote.”

After several near-fatal incidents, both sisters enrol in Chen’s trials, which are increasingly compromised by Omega’s profit motives. Ultimately, Lam seems to suggest, the drug crisis — and substance use disorders more generally — will not be solved by a single pill.

Lam’s pacing of the plot is methodical, and his prose is thorough and precise. In particular, his toggling of the narrative perspective between Chen and Claire facilitates an illuminating — and deeply affecting — examination of the bond between doctor and patient. At times, however, On the Ravine falters in its dialogue. A high school student tells Chen that he wants to sober up and start dating “like normal girls, doc, nice girls, clean girls, from my church, not like these druggie girls. Because you know doc, I’m not like the other people here.” One doesn’t doubt the patient’s desire to get sober or even his naive sense of superiority. But the construction of his voice reads like a clichéd film script — what a streetwise teenager of another era might be expected to say. This is not to suggest that Lam fails to convey the human tragedy of the drug crisis; a sense of loss and despair is palpable throughout the novel. Like Bloodletting & Miraculous Cures, this is a deeply felt book, clearly enriched by Lam’s first-hand experience.

In one of his letters to the medical student, Chen writes that a doctor’s task is to “peer through anger and frustration in order to nurture dreams.” This statement might just as accurately be applied to On the Ravine. Addressing the tragedy of the situation head-on and refusing to provide tidy resolutions, Lam offers a vital portrayal of the perseverance required of both patient and doctor to envision a life on the other side of addiction.

Aaron Obedkoff studies English literature at Concordia University, in Montreal.