In “Casual Notes on the Mystery Novel,” written in 1949, Raymond Chandler advised that “a really good detective never gets married.” Chandler was always careful not to entangle his best-known protagonist, Philip Marlowe — the star of seven novels, including The Big Sleep, from 1939 — in any sort of long-term romance. He believed such abiding affairs sapped vital tension from mysteries by introducing a type of suspense “antagonistic to the detective’s struggle to solve the problem.” This philosophy has long been a guiding principle for American noir fiction. Hence the genre’s history of steadfast bachelor heroes, from Frank Chambers, the drifter who narrates James M. Cain’s classic The Postman Always Rings Twice, to Bud White, Ed Exley, and Jack Vincennes, the policemen at the centre of James Ellroy’s neo‑noir L.A. Confidential.

It wasn’t until 2012 that Gillian Flynn’s blockbuster novel Gone Girl turned this formula roundly on its head, kicking off a new subgenre: domestic noir. Where classic noir reveals the venality of public institutions — the lie of good government, the corruption of the law — domestic noir scrutinizes the institution of marriage. These stories suggest that wedded life is a site of tremendous narrative tension, that husbands and wives are just as crooked as cops and criminals. At their heart lies a simple but compelling question: How well do you really know your other half?

Adam Sternbergh’s fourth novel, The Eden Test, is domestic noir par excellence. The not so happy couple: Daisy, a thirty-two-year-old theatre actor haunted by her violent past, and Craig, a thirty-eight-year-old marketing writer with a fondness for sleeping around. After two years of marriage, the giddy romance of the pair’s early days has deteriorated into a sordid routine of resentment and anger: “Maybe when you fall in love and it feels like sailing off a cliff, eventually you fall through the air far enough that you hit bottom with a thud.” In a last-ditch effort to save their relationship, Daisy signs them up for the Eden Test, a week-long marriage repair scheme at a cabin in the woods of upstate New York.

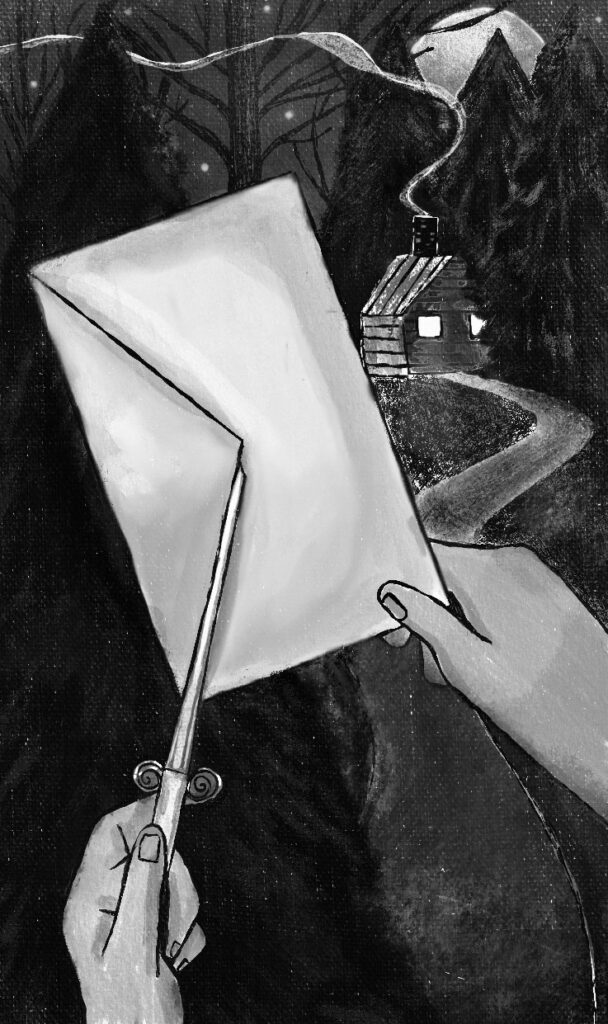

After they get settled, an envelope arrives every morning containing a searing hypothetical question: “Would you change for me?” “Would you sacrifice for me?” “Would you fight for me?” The idea is that feuding couples will discuss these prompts, honestly and thoroughly, and their relationships will emerge renewed, as per the test’s slogan: “Seven days. Seven questions. Forever changed.” Initially, the plan seems to be working; Craig, who had been intending to leave Daisy, begins to reconsider. But a series of ominous encounters with strange characters at the cabin and in the nearby town, including a deer hunter whose “forearms and hands are glistening with dark red gore, like he’s been elbow-deep in something,” suggest that the Eden Test’s premise may be less hypothetical than it seems.

Searing hypotheticals for husband and wife.

Joanna Turner

A clap. A shot.

From the woods.

He looks up.

The echo ricochets past the porch.

Sternbergh is more expansive with the psychology of the characters. Craig is especially well rendered. A preening, spineless yuppie whose personality revolves around living in New York and eating at trendy restaurants, he also has virtues, including natural charm, a sense of humour, and a functional (if primitive) moral compass. Such good qualities imply that, crucially, he can be redeemed.

As the novel ramps up, it becomes apparent that Craig’s redemption is the true project of the Eden Test. The selfish opportunist must fight for his wife — literally. Although the novel initially seems to invest in the counselling and love languages of contemporary couples therapy, it ultimately favours an older romantic tradition: a hero’s trial of commitment, strength, and moral fibre.

In 2012, Sternbergh wrote the essay “How the American Action Movie Went Kablooey.” He argued that films like Commando, Die Hard, and RoboCop are brilliant not only because of their entertainment value but because they allegorize the decay of an American empire that presumes almightiness. Such works manage the “nifty artistic trick of both embodying and critiquing this quintessentially adolescent dream of dominance,” providing “fantasias of cartoon violence” that serve as “canny dissections of our lust for cartoon violence.” Indeed, cultural studies scholars like Stuart Hall and Janice Radway have long argued that the best genre fiction both entertains and informs. With The Eden Test, Sternbergh showcases an expert understanding of noir’s entertaining elements: the drip-feed of suspense, the morally dubious characters, the pyrotechnic denouement. But what of its bigger idea?

One clue might lie in the test’s questions: “Would you fight for me?” “Would you die for me?” “Would you kill for me?” Their querulous, pleading tenor evinces not so much exultant affirmation of the marriage bond as deep-rooted anxiety about its endurance. Today, marriage as an institution is going through a crisis of legitimacy. When Craig says tying the knot is “unnatural,” he channels a sentiment popular among his age group: millennials. In the United States, those born between 1981 and 1996 are the first generation where the majority — 56 percent — remain unmarried. In Quebec, 43 percent of couples are common-law spouses, cohabiting but remaining unmarried — up from 30 percent in 2001. In a cultural landscape more and more dominated by such relative informality, The Eden Test asks readers if conventional matrimony still means anything at all.

For Daisy and Craig, it does, though that meaning is not necessarily pretty. At the end of Gone Girl, the troubled spouses Amy and Nick reunite despite having spent the entire novel locked in psychological warfare. The Eden Test affords its protagonists a similarly pyrrhic reward. In testing their commitment to each other, Daisy and Craig irrevocably change the nature of their relationship — for better or for worse.

Richard Joseph lives and studies in Montreal.