One morning in 1996, I got a call from David Radler, chief operating officer of Hollinger International, the company that had just taken control of my paper. He wanted to know why, as editor of the Vancouver Sun, I’d let our business columnist call one of his Howe Street stock-promoter pals a crook.

“Because he is a crook,” I said as neutrally as I could manage.

“Well, of course, he’s a crook,” Radler replied. “Everybody knows he’s a crook. How is that news?”

I feel a little bit that way about The Postmedia Effect, Marc Edge’s latest excoriation of the foreign-financed corporation that has stripped Canada’s biggest newspaper chain as bare as a Christmas turkey after Boxing Day lunch. In each new book, Edge’s outrage and exasperation with grasping corporate owners, predatory lenders, meddling news managers, somnolent government regulators, erratic politicians, and a seemingly indifferent public intensifies. It’s hard to argue with any of it. But is it news? The news about the future of journalism that we need now?

What happens when newspapers don’t engage audiences the way they used to?

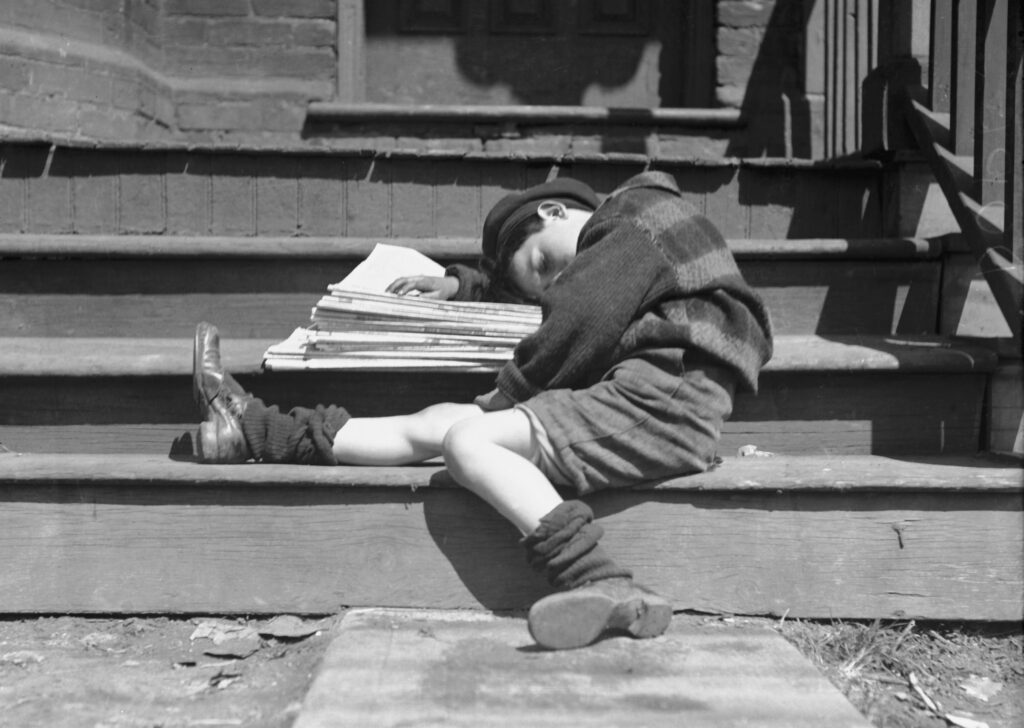

Fonds 1257, Series 1057, Item 1951; City of Toronto Archives

The newspaper group that was known for a century as Southam Inc. was bought and sold three times between 1996 and 2010. Each deal multiplied its debt load. The last transaction, in which Postmedia Network emerged out of the ruins of bankrupt Canwest Global Communications, was financed with suffocating quantities of American cash. The deal openly violated the spirit of the law prohibiting foreign ownership of more than 25 percent of any Canadian media company.

Postmedia has been a national news calamity ever since. Already owner of many of the country’s most important papers, it bought up every news organization it could get its hands on: notably Sun Media and, latterly, Brunswick News. It pillaged the newsrooms, politicized the journalism, mixed editorial and advertorial, centralized decision making in Toronto and copy editing in Hamilton, and sent, by Edge’s count, more than $500 million in interest payments to its creditors.

Even more recently, Postmedia flirted with a partnership with Nordstar Capital, owner of the Torstar Corporation, with its seven dailies, more than seventy regional weeklies, and various magazines and websites. The deal was scrubbed shortly after it was reported in July, but Postmedia was clearly hoping to extend its flow of debt payments a little longer.

All of this has been an object lesson in what happens in the absence of effective enforcement of public policy and without civic-minded ownership willing to put service to the community before profits.

Postmedia Network, which operates more than 130 print and digital news titles across Canada, has figured in five of Edge’s books. Our author has some first-hand experience, having worked at the Vancouver Province and the Calgary Herald, in the genteel days when the chain was still called Southam and known for quality journalism. After that, he left to pursue an academic career.

Our author also brings an obsessive quality to his dense documentation of the ways Postmedia has cut costs, harvested revenues, and broken promises to federal regulators that it would preserve the editorial independence of the titles it scooped up. He captures the suits at their villainy, the bureaucrats bumbling, the politicians uncertain of the wind direction — and a handful of conscientious journalists and media critics trying to keep hold of deeper truths in a shallow world of spin.

But it’s not as if Canadians weren’t warned things would go sideways.

Fifty years ago, the Ontario senator Keith Davey condemned corporate concentration in the nation’s media and mused that news operations should be treated more like public utilities than like manufacturers. Tom Kent, once the editor of the Winnipeg Free Press, reiterated Davey’s warning in 1981, with his Royal Commission on Newspapers report. By that time, though, Southam and the Thomson Corporation had already carved up the Canadian market, closing papers to create monopolies in Ottawa and Winnipeg.

Legislators and regulators were deaf to the advice. The newspaper business was a nettle that no government would grasp and no trade association could discipline. Who wants to quarrel with people who buy their ink in barrels? Over the years, ownership became increasingly concentrated, while merged entities churned out profits that were multiples higher than those of most other Canadian industries. Until they didn’t. New digital businesses first took away newspaper classifieds, then wiped out a large percentage of all other categories of advertising. Because their audiences were so large, Google, Facebook, YouTube, and others also repriced all advertising downward. Suddenly, the newspaper owners who resisted any form of government intervention for decades were looking for handouts.

Edge is both unsympathetic and skeptical. In an earlier book, Greatly Exaggerated: The Myth of the Death of Newspapers, from 2014, he accused media companies of fabricating a “newspaper crisis” to justify increasing the concentration of corporate ownership and their pleas for taxpayer dollars. The proof? Newspaper chains continued to post profits for years after they started crying poor. He doesn’t believe there was or is a crisis that warrants government intervention. I think he is wrong.

Edge must look beyond the balance sheets to appreciate fully what has happened to newsrooms. A profit statement speaks to the success of the previous quarter, not the health of a company. The market failure he ignores is in the loss of publishers’ ability to finance reporting that’s socially and politically essential and to create broad, diverse, and loyal news audiences.

Newspapers bleeding advertising revenues can stay afloat only by slashing costs. Once they have wrung all possible efficiencies out of production and administration, those savings must come from cutting editorial and letting audiences shrink. Indeed, competition for dollars with digital giants is only the newspaper industry’s second-gravest problem. The dramatic readership declines are even more threatening to their long-term survival.

For many Canadians, the debate over whether there is or isn’t a market failure in newspaper journalism will seem inconsequential. Newspaper audiences are small — especially compared with those enjoyed by Google, Facebook, YouTube, and other players — and they are much older than the general population. But newspapers have long been the main source of breaking news and investigative reporting in our society. If there is, in fact, a market failure, everyone who is looking for Canadian news on any platform — beyond stage-managed media events and weasel-worded press releases — will be affected.

Using numbers from Statistics Canada, Canada’s National Observer estimates that the number of journalists in this country fell from 11,600 in 2015 to 9,100 in 2019. The share of freelancers has risen from 5 percent to 17 percent. Meanwhile, new jobs in digital journalism are not keeping pace with lost ones in print. Television news, too, is retrenching as younger people abandon cable subscriptions and audiences shrink and age. Bell Media reports that it is losing $40 million a year on its news channels, which include CTV and CP24. It has asked government regulators to reduce the amount of local content it is required to produce and broadcast.

In the United States, where many papers are, like Postmedia, in the grip of hedge funds, almost 60 percent of newspaper newsroom jobs have disappeared since the early 1990s. That’s 40,000 positions. Digital news operations, having created just 10,600 jobs, hardly make up the difference.

Despite such trends, Edge insists that papers will adjust to competition with the digital giants as they did with television. “Publications which have . . . invested in quality content and developed a loyal base of online subscribers,” he recently wrote in the Globe and Mail, “have found that there is still a solid business model for newspapers, even in print.” Again, I don’t share Edge’s optimism about the long-term fate of all but a few of Canada’s publications.

Across the industry, the titles adjusting best are those targeting a high‑end demographic. These include the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal in the United States and the Financial Times in the United Kingdom. It is not a coincidence that they have all emerged from cities with large, affluent elites and now market their work to the wealthy and powerful around the world.

In Canada, a similar trend began in the 1980s, when the Globe and Mail intently pursued business managers and owners, professionals and entrepreneurs — the top 3 percent of the population by income and education. The National Post, launched in 1998 by Conrad Black and Ken Whyte out of the Financial Post, seeks a similar audience, because it’s the one advertisers will still pay for. These are readers who can afford hefty subscription fees or who can bill their employers for them.

There is no evidence that “quality content,” however that might be defined, will create its own audience and business case. Competition with streaming services is a big reason why. Neither print nor TV news competes effectively anymore as a form of entertainment, which was once a key to their ability to engage broad audiences. And as revenues have fallen, both print and TV news have dramatically scaled back their promotional efforts to build and retain audiences.

People who love the news find it hard to understand that for large numbers of their peers, keeping up with current events is a choice, not a need. Marketing and aggressive distribution strategies are essential to maintaining readership. Without them, newspapers lose readers to the distractions the digital revolution has made available.

Yes, digital newspaper subscriptions are growing — yet slowly and from a small base of readers, generally younger than print subscribers but older than the average population. Furthermore, engagement with news sites is very different from engagement with print. Readers typically spend about forty minutes with their weekday papers and more on weekends. That compares with an average of less than two minutes per visit at the top fifty U.S. newspaper websites, according to the Pew Research Center.

None of this suggests a solid business case for a news operation capable of carrying out the broad and varied public purposes of the past.

It is true that print titles have proven to be more resilient than most journalists and managers expected them to be. The remaining readers remain deeply attached to the papers they grew up with. But the same loyalty has not been proven for digital.

A great deal of Edge’s book is taken up with a detailed account of how the industry lobbied government for handouts and for leverage in trying to compel Google and Facebook to share advertising revenues with them. Because he believes newspapers don’t need government support, he disparages all those involved. He is especially cynical about dollars directed to Postmedia.

I was involved in the early stages of the industry’s lobbying efforts on this front. Everyone understood that whatever resources came from Ottawa had to be dedicated to reporting — and that not one penny could be allowed to spill over to Postmedia executives’ bonuses or interest payments to foreign lenders. Even so, the federal government initially balked at the idea of support. In 2017, Mélanie Joly, then the heritage minister, refused to “bail out industry models that are no longer viable.” But as it became clear that no alternative business case was emerging rapidly enough to preserve reporting levels — especially for local and metropolitan papers — the federal government began to provide arm’s-length assistance.

I was not and would not have been part of the lobbying for what became Bill C‑18, an act that compels the likes of Google and Facebook, in particular, to compensate news organizations whenever a user links to Canadian news content. That’s because, in my experience, the presence of social media did those organizations more good than harm. I think Edge is right to criticize the effort and the resulting legislation. While it is tempting to blame Google and Facebook for “stealing our advertising,” they have bigger audiences, lower prices, and vastly better technology in which they have invested billions of dollars. There are lots of good ways for Canada to regulate foreign giants that have so much influence over our digital advertising market. Forcing them to compensate news originators for links is not one of them.

In his final pages, Edge writes, “Postmedia suddenly started sinking in 2022.” This makes sense only in the world where the newspaper crisis is a myth, which it isn’t. And by the author’s own deeply detailed account of its depletion, there was nothing about Postmedia’s sinking that was sudden. It was the inevitable result of the “vulture capitalism” of his subtitle.

Despite his apparent surprise, Edge is not at all disconcerted by Postmedia’s decline. He hopes it fails, so something superior can appear in its place. I agree with Edge that locally owned titles unburdened by crushing foreign debt would fare better. But the scuttled deal proposed with Nordstar Capital indicates Postmedia has no interest in setting its titles loose until the last dollar has been extracted.

So what should be done about the threat to reporting? Edge’s answer is to let the market take care of the bad players and hope for something else to emerge. While we await new private sector backing for journalism, our existing capacity may be even further compromised. Perhaps something better will come along soon. Perhaps later.

On its present trajectory, the reach of newspapers will continue to shrink. Subscription fees will go much higher to make up for lost advertising. Marketing and distribution efforts will focus on rarefied audiences. Once a vital force for the creation of a broadly informed electorate, newspapers will become yet another instrument of division between the elite they seek to engage and everyone else.

John Cruickshank has worked as a newspaper editor and publisher, broadcasting executive, and Canadian consul general in Chicago.

Related Letters and Responses

Mark Abley Pointe-Claire, Quebec

@rodmickleburgh via Twitter

Marc Edge Ladysmith, British Columbia