Anxieties about artificial intelligence replacing writers clearly inspired Do You Remember Being Born?, the latest by Sean Michaels, whose debut novel, Us Conductors, won the 2014 Giller Prize. Rather than building a story around a new author contending with this emerging threat, Michaels centres his tale on an established poet working with the technology. This focus grounds a narrative about cutting-edge robotics in a conventional theme: how growing older impacts one’s usefulness, economic security, and ability to relate to others.

Irreverent, quick-witted, and eccentrically attached to a tricorne and cape, the seventy-five-year-old poet Marian Ffarmer is comfortable with the spareness of a hermitic literary life in her late mother’s Manhattan apartment. But she hasn’t saved much money, and with her middle-aged son struggling to buy his first home, she feels “humiliated” that she can’t help him, even if “the son of a poet grows up knowing his mother will not take care of him, not in certain ways.”

So when a letter arrives inviting her to participate in a “historic partnership between human and machine” over one week in California for $65,000, Marian agrees. Her task? To compose an original “long poem” in collaboration with a groundbreaking new AI: Charlotte. The “2.5 trillion-parameter neural network” was programmed by the Company — a stand in for Silicon Valley giants like Microsoft and Meta — with the goal of creating “the kind of work that endures as a monument in all of human history.” Marian regards such a lofty ambition as hubris, so the partnership between woman and machine begins on shaky ground. As working with the AI challenges her identity as a poet and a mother, the tremors only get stronger.

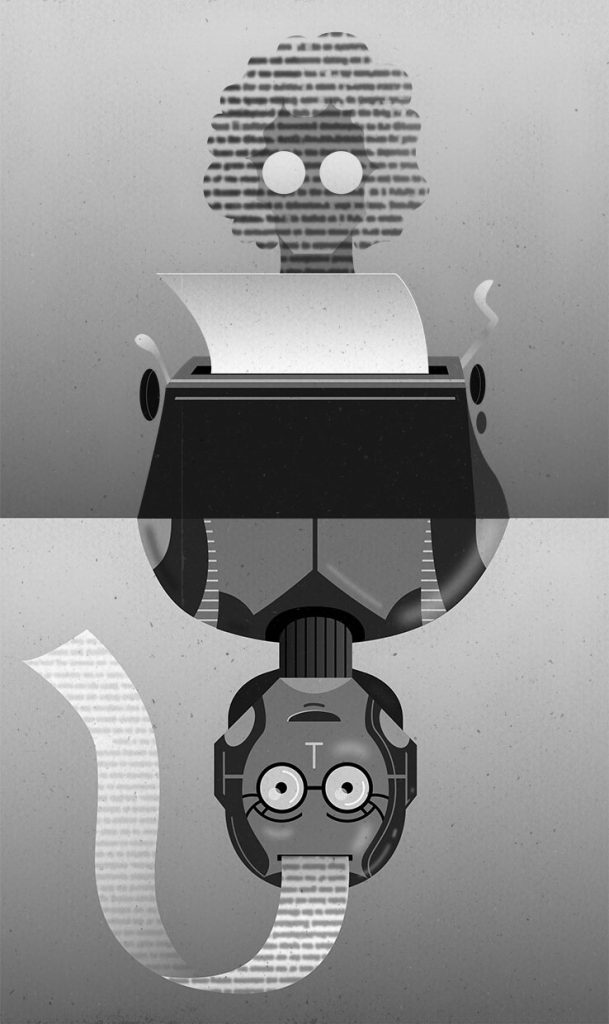

Working toward a collaborative composition.

Blair Kelly

Initially, Marian dismisses Charlotte’s generated lines as “stupid,” but working with the computer prods her to examine her own artistic process. Marian can’t help but express herself with others’ opinions in mind; Charlotte, on the other hand, has no ego. The AI is “never pretending.” Its artistic efforts are “just the product of its algorithms, like a cash register’s crinkly receipt.” Dispirited, Marian asks herself, “Was there anything more natural than that?” She concludes that Charlotte “did not share my weakness” and wonders if, despite her success — including a Pulitzer Prize — she’s never expressed her true self through her work: “I did not feel like a fraud so much as something vaguely imaginary, a sort of mirage.”

Meanwhile, Marian’s efforts to grow close to real people are torturous and awkward. She struggles to connect with a Greek poet she meets by chance at her hotel and imagines that his parting phrase —“Kalinikta,” which means “good night”— is a spell meant to render her invisible. She buys a CD for her amiable driver, Rhoda, but upon hearing the music that sounds “like a reggae song being subjected to an overzealous massage,” she demands that it be shut off: “What is this?” As Marian spends more time around others, she finds herself warming to them, and she begins opening up. Her disclosures culminate in a heartbreaking flashback where we learn the reasons for her self-imposed isolation. Questions arise: Will Marian, at long last, overcome her traumatic shackles? Can she do so in time to deliver the poem to her employer and redeem herself in the eyes of her son?

While the novel uses AI as a thematic vehicle — to deconstruct the myth of the solo writer and examine the bonds between creative people and their environment — technology also played a direct role in its creation. In his author’s note, Michaels describes collaborating with a grad student, Katie O’Nell, to build Moorebot, a “custom poetry-generation software” trained on a “corpus that includes the collected work of Marianne Moore.” He used Moorebot and OpenAI’s GPT 3, a popular large language model, or LLM, to produce Charlotte’s verse and some parts of the novel’s prose. These sections, highlighted in grey, can be as short as a word or as long as a paragraph. Readers might question whether the seemingly arbitrary computer-generated sections mean anything — but this effect is most certainly deliberate.

The structure of the book also recalls the process of using LLMs. First you tell the AI who it’s supposed to be: “You are a mother of three,” “You are a lonely farmer,” “You are a wise therapist from Mumbai.” Then you tell it what you want it to write, and it produces something. Much of the novel follows a similar pattern. Divided into chapters that alternate between the second-person past and the first-person present, it moves between context and action, prompt and product. The effect can be disorienting, but the arrangement heightens the impact of the protagonist’s growth. The past-tense chapters contextualize Marian’s reclusive behaviour by detailing her peculiar relationships with her mother and ex-husband, among others, and putting them in the second person creates the impression that Marian can talk about these things only because they’re not about “her” but rather about some imaginary “you.” This disconnection makes her seem even lonelier, and her eventual turnaround is all the more satisfying.

Despite her flaws, Marian is likeable. She appreciates “curious and uncondescending people,” playfully needles the optimistic young employees of the Company and the “glossiness of their spirits,” and takes infectious joy in words like “unfurl” and “wish,” which to her ear are “covert onomatopoeia, the sounds of things that did not necessarily have sounds.” But the more we learn about what she has done and whom she has hurt, the harder it becomes to respect her. Without spoiling the story, suffice it to say the other characters forgive her so easily that their behaviour defies logic. No one withdraws from her. No one yells at her. In fact, throughout the novel, no one expresses any emotion that doesn’t directly contribute to her development. It’s too tidy, too Dickensian; by the end, it’s as though Marian has met with the ghosts of past, present, and machine and emerged renewed.

Some readers might wish that Marian faced harsher consequences. Still, most will probably be glad that Marian, who’s fundamentally good-natured, comes out on top. “Back in New York, the apartment feels different,” she observes. “Less like a refuge, more like a staging post.” Indeed, Marian learns to see herself as more than a poet — because poets are more than their poetry. They aren’t machines, after all.

Omar Khafagy is a copywriter in Hamilton.