There isn’t a lot of singing in Frontier, which debuted on Netflix in 2016. With each episode, the show about the eighteenth-century fur trade attempts to prove that the pages of Canadian history conceal enough intrigue to sustain prestige-ish television. (Three seasons’ worth, anyway.) Starring the towering, glowering, sometime superhero Jason Momoa as Declan Harp — a half-Irish, half-Cree thorn in the side of the Hudson’s Bay Company — Frontier has blood, sex, revenge, and double-crosses. But, except for a few bars half hummed by its lone Canadien character, Jean-Marc Rivard, no one ever seems to break into song.

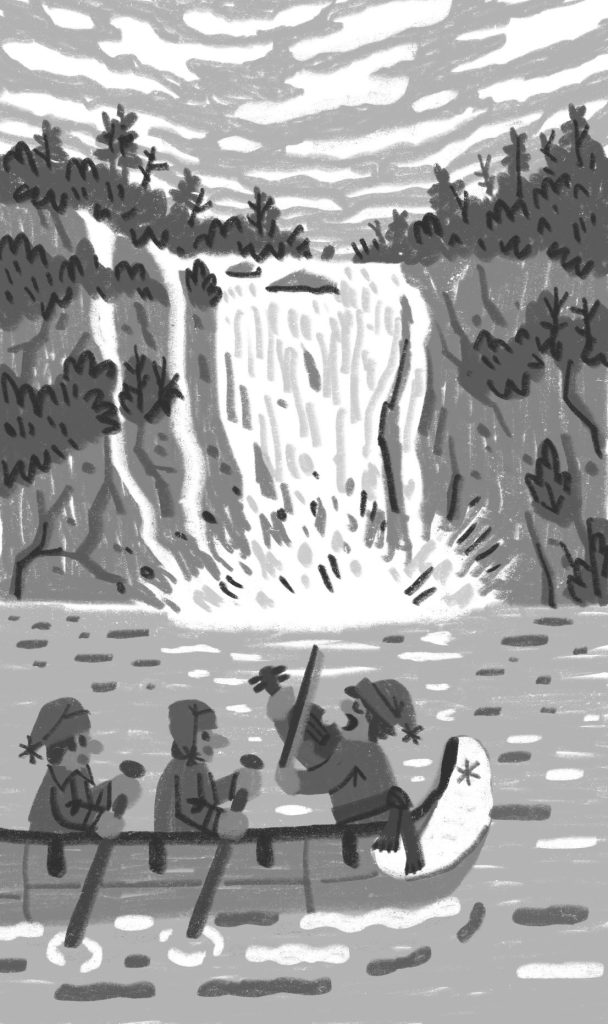

A fur trade with so little music (and so little French) would likely leave Sébastien Langlois and Jean-François Létourneau, the authors of En montant la rivière (Going up the river), scratching their heads. In their telling, the only thing more Québécois than two folk music fans meeting in a hockey locker room and deciding to write about their shared passion would be, for better or worse, the image of twelve burly men paddling a canoe and singing at the top of their lungs about a girl they left behind. There’s no twenty-first-century music in Quebec without the voyageurs, and there would have been no voyageurs without the songs that kept them paddling.

Indeed, traditional music — or trad — is alive and well. Groups composed of fiddle, accordion, and bass, with vocalists out front tapping their feet, attract eager listeners to bars and summer festivals from the Eastern Townships to the Gaspé. There are groups playing trad trad (old songs, old styles) but also an expanding number of neo trad variations, including electro-trad, trash-trad, and blends of pop, country, metal, and reggae. Click through the many YouTube clips devoted to the genre and a consistent through line starts to emerge. There’s a lot of flannel, many earnest faces, plenty of cozy cabin sets that look pulled from the 1970s, and not a few horse-drawn sleighs. Trad artists might, as members of the popular group Le Vent du Nord explain in a video for their 2022 album, be trying to get at something more than nostalgia, but it’s there all the same.

There’d be no voyageurs without the songs.

Alexander MacAskill

The spirit is not exactly one of conservatism — a point En montant la rivière makes multiple times. “Oral tradition is wrongly perceived to be a finished object, fixed in the past, permanent,” Langlois and Létourneau write. The Quebec trad song often suffers greatly from this misconception: “Unappreciated, rarely sung, too little shared, it is the victim of prejudice, found to be cheesy, dowdy, passé.” Conservatism deadens, but genuine trad is alive. It may be full of memory and longing, but it is also ever evolving.

UNESCO defines intangible cultural heritage as, in part, “traditional, contemporary and living at the same time.” It’s a kind of collective memory that’s always changing to suit its moment — not fixing the past or revising it but bringing into focus maybe this part, maybe that. Langlois and Létourneau focus on the part that encompasses the everyday realities behind the foundational myths of Quebec and a larger transcontinental francophone experience.

In folk lyrics, both new and old, Langlois and Létourneau find memories of forgotten histories and connections obscured by time and by narratives written expressly to facilitate conquest. In many cases, those narratives foreclose the possibility of connection between Indigenous people and settlers, even between settlers and their French roots. In Frontier, for example, Jean-Marc hums “À la claire fontaine,” with lyrics likely composed by a now nameless troubadour a century or more before the song crossed the ocean. Today a kind of national hymn of anti-British resistance and practically required singing at Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day celebrations, “À la claire fontaine” exists in “a hundred versions, with words and melodies that have been adapted to fit the contexts in which they’re sung.” As the refrain goes, “I’ve loved you for so long / I will never forget you.” It’s as if the singer is saying, “I wish things could go back to the way things were. If I could do it again, I wouldn’t turn you away.”

Separating nostalgia from conservatism is not always easy. Nostalgia has a glow to it, making the past seem better than it was. Spend too long away from home, and it’s not just the good parts you start to miss — the sense of belonging, your family and friends, the familiar food — but the bad parts, too, which can start to look kind of good. So good, you might think, that everyone should adopt them. What was once innocent melancholy becomes a strident inflexibility that rejects difference, change, and any other challenge to the perceived perfection of a lost time. “Nostalgia,” the cultural critic Svetlana Boym wrote, “can be both a social disease and a creative emotion, a poison and a cure.”

Boym argued that longing for an ancien régime is often more than longing for the way things were. It is also a desire “for the unrealized dreams of the past and visions of the future that became obsolete.” It is no accident that such longing intensifies in times of change. Take the Quebec Winter Carnival, which has been running, off and on, since 1894. Its mascot, Bonhomme — a giant snowman sporting a voyageur tuque and an arrow sash — is a relatively recent addition. He made his debut in 1955, two months before the Richard Riot in Montreal offered a violent prelude to what would end up being the Quiet Revolution. In the music of the ’60s and ’70s, Langlois and Létourneau point out, “the voyageur became a ‘Québécois,’ prepared to vote ‘yes’ in a future referendum.”

The Quiet Revolution gave Quebec modernity and identity, as well as the promise of self-determination and the temptation of essentialist nationalism. Langlois and Létourneau acknowledge that folk music, with the larger oral tradition of which it is a part, has the potential to feed into both promise and temptation: “The role of oral tradition in general has always been paradoxical, an escape hatch and a protest on one hand, and the foundation of traditional society on the other.” But the variation and adaptability they find in so many songs inclines them toward optimism. Like Boym, Langlois and Létourneau seek memories that are full of contradiction and connection, hoping to find something, even a melody differently interpreted, that isn’t Québécois or even French Canadian but rather a witness to violence and alliance, negotiation and betrayal, arrival and displacement. If nostalgia offers freedom, it isn’t “a freedom from memory but a freedom to remember, to choose the narratives of the past and remake them.” There is a lot resting on that choice.

Ruth Jones is one of the magazine’s contributing editors.