When I was an undergraduate English major, my fiancé was scandalized that I had never read Moby-Dick. But it was American, I explained, and I was devoting myself to British authors. He responded, sensibly, that that was beside the point, so I produced another reason, which became a family joke: “Besides, I don’t read animal stories.” (Honesty compels me to confess that at age seven, I did very much like Eric Knight’s Lassie Come‑Home.)

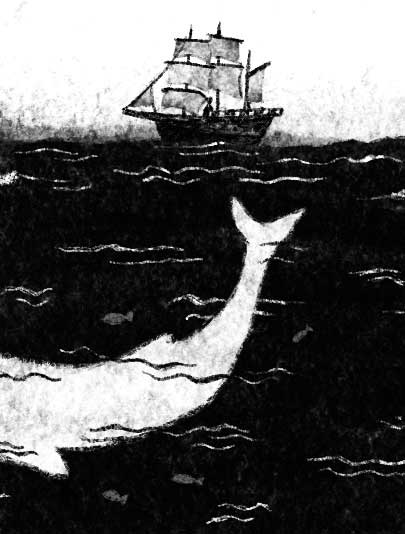

I continued avoiding Moby-Dick for half a century, until I was invited to read a book I felt guilty about shunning. I hadn’t been aware that guilt was involved, but I immediately saw in my mind’s eye the words “MOBY-DICK” in huge letters. It was time to make my long-delayed acquaintance with Herman Melville’s great white whale.

Now that the task is done, I can see I was hedging my bets: rather than buy the novel, I borrowed it from the library. When I announced my plan to friends, two men reverently intoned the word “masterpiece,” and three women remembered the classic as a tough, unrelenting slog. The women’s reactions didn’t trouble me: perhaps they had been too young when they read it or too unused to Victorian sentences the size of small essays. As it turned out, it was those two poles — masterwork and boring — between which my reading would swing like a boom on the good ship Pequod.

Nicole Iu

Moby-Dick begins oddly, with an etymological history of the word “whale” in thirteen languages and scores of quotations about the mammal — an indication of the high seriousness with which Melville treats his subject. Once the novel proper starts, in nineteenth-century New England, it strikes me as a sampler of great writers. The narrator, Ishmael, is reminiscent of other wayward and incorrigibly digressive characters who came before him, like Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, and after him, like James Joyce’s Leopold Bloom. Later come echoes of Shakespeare and the Bible, while Captain Ahab, who makes a fateful, tragic resolution to avenge Moby Dick’s amputation of his leg, reads like a Thomas Hardy figure avant la lettre.

The first 100 pages, one-sixth of the total, clip along with preparations for a four-year whaling voyage. When Ishmael ends up in bed (platonically) with the tattooed Polynesian harpooner Queequeg, their happy pillow talk promises a fine bromance. Alas, no. The novelist has other priorities, largely the tortured, charismatic character of Ahab and what Melville sees as the irresistible fascination of whales in all their aspects.

At times, Melville’s descriptions of the hunt are masterful, as when the spouts of a crowd of sperm whales resemble “the thousand cheerful chimneys of some dense metropolis.” He can distill an emotional state into one pithy, alliterative phrase: “Ahab and anguish lay stretched together in one hammock.” Trapped between the claustrophobic boat and the infinite sea, Ishmael sounds his worries about the country he left behind: its racism, its attachment to money, its tentative grasp of democracy. Although profoundly pessimistic, he has a dry wit and a heart. While Ahab descends into greater selfishness, Ishmael’s understanding deepens.

All this is wonderful, but Moby-Dick is robbed of its shape and momentum by Melville’s obsession with whales. Whole chapters are devoted to their colours, head shapes, skeletons, edible parts, ambergris, spermaceti, butchering techniques (including the harvesting of blubber), and much, much more. Melville frequently describes Ahab as a monomaniac, but the author has his own fixation. Like the crank at a dinner party who bends your ear about some arcane subject, he gets increasingly lost and delighted in the details while the whole skitters away. Overwhelmed by all the facts, I began to fear a pop quiz at the end of each chapter. At other times, I entertained the fantasy that I had somehow got my hands on the bloated first draft of the novel — before an editor cut most of the whale miscellanea and turned the book into a masterpiece.

Masterpieces, of course, are in the eye of the beholder, and many will disagree vehemently with me. There’s no possibility of “I told you so” when judging artistic merit, and I had been willing to be converted. But when I said, facetiously, that I did not read animal stories, I could never have fathomed just how compulsive, encyclopedic, and oblivious this particular animal story would be.

Katherine Ashenburg is a novelist in Toronto and the author of The Mourner’s Dance: What We Do When People Die.

Related Letters and Responses

Brydon Gombay Toronto