Today, Honoré Jaxon would be labelled a “pretendian.” In his own lifetime, he was variously described as a loyal secretary, a dangerous rebel, a blue-collar rabble-rouser, a gifted orator, and a lunatic. Always, he has been on the margins of history. But as Donald B. Smith, an emeritus professor of history at the University of Calgary, writes in this intriguing and readable biography, “Occasionally those on the fringe may see things more clearly than those in the mainstream.”

The resurrection of this volume, first published nearly twenty years ago, is almost as interesting as its resurrected subject. But first, the facts of Jaxon’s life: the reliable facts that Smith has truffled out of archives, interviews, registers, memoirs, yellowing newspapers, learned journals, censuses, unpublished manuscripts, and family letters. This historian is certainly a hound for documentary proof. Honoré Jaxon has 220 pages of text, followed by almost 100 pages of acknowledgements, endnotes, and bibliography.

What Smith discovered was that Honoré Jaxon was born Will Jackson in 1861 in Toronto, the son of recent English Protestant immigrants, and that he grew up in Wingham, Huron County, where his father operated a general store. Young Will was a brainy and intellectually curious fellow: he taught himself German and completed three years of classical studies at Toronto’s University College before being dragged west by his family in 1882. In Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, Will joined his father behind the counter of the latter’s new general store, selling farm implements, among other items.

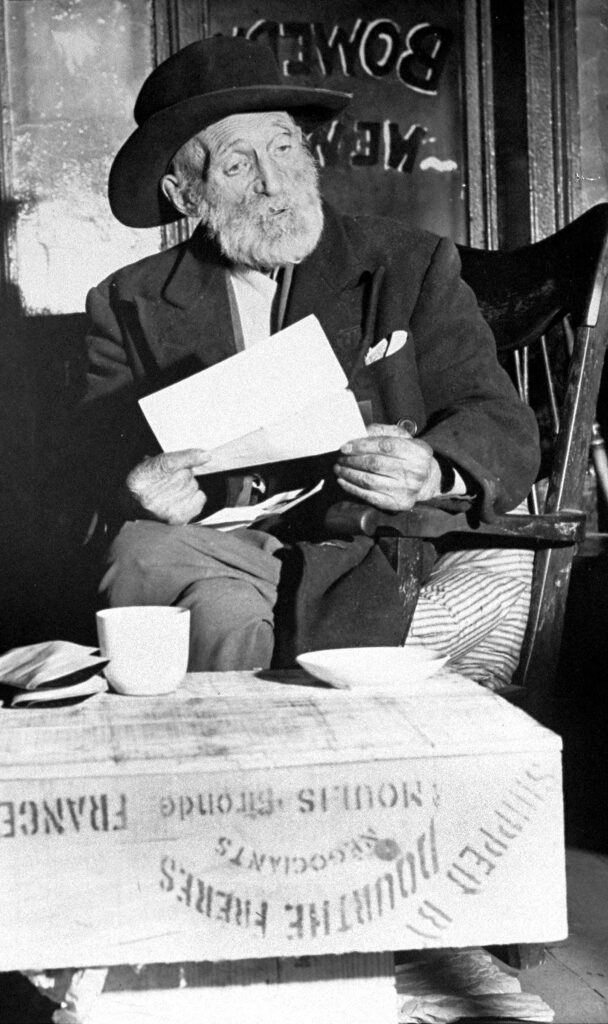

Honoré Jaxon in the Bowery, New York City.

Hal Mathewson; New York Daily News Archive; Getty

For much of his early life, Will Jackson appears to have shared all the assumptions of English immigrant families of the time, including a belief in Imperial Britain and in the notion that Indigenous peoples in Canada were “a vanishing race.” While he was in Saskatchewan, however, his attitudes began to evolve. He learned of western wheat farmers’ deep hatred of high tariffs imposed by Ottawa. These duties forced up the cost of machinery while giving no protection to western grain on the world market. By the age of twenty-three, Jackson was secretary of the local Prince Albert farmers’ union, railing against Ontario manufacturers and for provincial rights.

In 1884, the young man met Louis Riel, the Métis hero of the 1869–70 uprising that had forced Ottawa to create the province of Manitoba. After fourteen years of exile, mostly in the United States, Riel had returned to Manitoba to press for Métis land rights; Jackson unofficially became his private secretary. In a family letter, Jackson wrote of Riel, “The oppression of the aboriginals has been the crying sin of the white race in America and they have at last found a voice.”

Jackson began to imagine a society in which English and French, First Nations and Métis would be equals. But it all went horribly wrong. At the clash between Canadian soldiers and Métis fighters at the Battle of Batoche, Jackson was seized and imprisoned, though he had never advocated armed resistance or fought in any battle. Edgar Dewdney, the lieutenant governor of the North-West Territories, packed Jackson off to a lunatic asylum at Lower Fort Garry, and Louis Riel was sentenced to death in July 1885. From this moment onward, the young idealist donned a Métis headband and worked to construct a Métis identity for himself. He escaped the asylum and fled across the forty-ninth parallel to the United States, where he changed his name to the French-sounding Honoré Jaxon, invented a Métis parent, and dedicated himself to the working class and the Indigenous peoples of North America.

There would be several more roles in the Jaxon story: labour organizer, owner of a construction company, and popular lecturer on American Indians. In Chicago, he became a minor celebrity and befriended the architect Frank Lloyd Wright. In 1894, the Chicago Times commissioned Jaxon to cover the first national crusade against unemployment: Jacob Coxey’s march to Washington. By now, several observers were skeptical of this wild radical who could never resist a soapbox and lived in shabby lodgings, and many concluded that the “half-breed Indian” was half crazed. Others, however, found him impressive. “He looks like an Indian, talks like a graduate of Oxford and writes like a professor of rhetoric,” The Saturday Evening Post once declared. Meanwhile, Jaxon, who had converted from his family’s Methodism to Roman Catholicism during his months with Riel, embraced the Baha’i faith.

In 1907, Jaxon, now married, returned to Western Canada to gather notes for a planned memoir on the 1885 uprising. The accumulation of materials for this history became a lifelong obsession. But soon he was back in the United States and once again reinventing himself — this time in New York City as the landlord of several Bronx properties. The avowed socialist was lousy at property management, and he became increasingly eccentric and isolated. The end of his story is pathetic. The ninety-year-old pack rat and veteran of the second Riel Rebellion was evicted from a Manhattan basement in 1951, along with three tons of paper, pamphlets, and books that he had amassed for his unwritten memoir. Almost all his archive went to the city dump; Jaxon himself died a few weeks later and was buried in the Salvation Army section of a Flushing cemetery.

Why should we care about such a bizarre character, who, even during his own lifetime, caused eyeballs to roll? “For his contribution to our understanding of Louis Riel alone,” Smith argues, “Honoré Jaxon, once known as Will Jackson, deserves a prominent place in Canada’s historical memory.” That is a bold claim, given the rapid evaporation of any historical memory in this country. How many twenty-first-century Canadians can even identify the historical importance of Louis Riel himself?

The reappearance of Honoré Jaxon tells us a lot about the malleability of history. Jaxon first caught Smith’s attention half a century ago, when, as a graduate student at the University of Toronto pursuing a doctorate in Indigenous history, he saw mention of the eccentric figure buried in a footnote. In the intervening years, while teaching at the University of Calgary and producing several well-received books, Smith doggedly accumulated material about the supposedly Métis maverick. He searched out old-timers who half remembered the man; in 1979, he met Jaxon’s eighty-three-year-old niece, who gave him a cache of correspondence. Finally, Coteau Books, a small literary press in Regina, published Honoré Jaxon: Prairie Visionary in 2007. It was greeted with respectful if muted attention and sold out its first print run. When the publisher went out of business in 2020, it returned its production files to its authors. The University of Toronto Press has used Smith’s in preparing this second edition.

Since Honoré Jaxon was first published, much has changed. There has been a rising tide of Indigenous self-assertion, fed by favourable decisions from the Supreme Court of Canada. Information about and interest in Indigenous history have also exploded. The 2015 report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission urged that more of this history should be taught in Canadian schools. Over this same period, suspicions of those who pretend to have Indigenous ancestry, often for personal advancement, have become a national concern.

Throughout his career, Smith has published numerous deeply researched books and chapters about Indigenous Canada, including Sacred Feathers: The Reverend Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby) and the Mississauga Indians, from 1987; “The Dispossession of the Mississauga Indians: A Missing Chapter in the Early History of Upper Canada,” included in Historical Essays on Upper Canada, from 1989; and Seen but Not Seen: Influential Canadians and the First Nations from the 1840s to Today, from 2020. During fifty years of scholarship, he has sought to understand why non-Indigenous Canadians so often failed to recognize Indigenous societies and cultures as worthy of respect and Indigenous people as equals.

Inevitably, this academic focus has meant that Smith has himself been caught up in recent debates about the roles of various nineteenth-century Canadians of both Indigenous and European origins. Although his own education was steeped in colonial assumptions and in the founding myth of Cartier, Champlain, and Charlottetown, Smith has consistently sought to incorporate Indigenous perceptions of time, land, and nature into his work. In Sacred Feathers, he explored the close friendship between Peter Jones, the brilliant Mississauga chief and Methodist minister, and Egerton Ryerson, as well as Ryerson’s efforts on behalf of First Nations. In Seen but Not Seen, he wrote that Sir John A. Macdonald’s record with the Indigenous peoples in the North-West in 1885 was “totally reprehensible, and his approval of the execution of Louis Riel a colossal error.”

However, if Smith was regarded as an original thinker at the start of his career, for his deep commitment to Indigenous history, he is now often derided as a defender of yesterday’s approach to history, thanks to his judicious search for balance. He has stuck his neck out. He argued that Egerton was not the father of residential schools, for instance, so there was no need to rename Ryerson University in Toronto. He has also maintained that Macdonald should be remembered for his success in moulding antagonistic provinces into a federation as well as for his appalling treatment of Indigenous people. Such “Yes, but . . .” arguments do not find much favour with a new generation of historians. Many of Smith’s academic contemporaries have preferred simply to duck controversy rather than risk crucifixion on social media.

Smith has written about other individuals who reinvented themselves as Indigenous North Americans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Long Lance: The True Story of an Imposter, from 1982, explored the life of Sylvester Clark Long, an African American journalist (possibly with Cherokee ancestry) who claimed to be the son of a Blackfoot chief. Published eight years later, From the Land of Shadows: The Making of Grey Owl told the story of Archie Belaney, the Englishman who embarked on a racial masquerade, becoming a supposedly Apache champion of the Canadian wilderness and Indigenous peoples. And now we have Honoré Jaxon, about the son of an Ontario shopkeeper who decided he was Métis.

Throughout this trilogy of books, Smith has laboriously constructed a detailed portrait of his subjects’ own actions, as well as their personalities and networks. What deep psychological needs drove them to walk away from their authentic origins and identify with peoples who, back then, were scorned as “inferior”? Who influenced their behaviours? How many Indigenous friends and acquaintances did they themselves have? What, if any, financial advantage did their pretendian aspirations give them? And what did they achieve in their assumed identities? Thanks to his careful research, Smith has presented these three controversial figures from our problematic past in all their contradictions.

But is Honoré Jaxon worth resurrecting? This biography introduces us to a settler who, in 1885, was looking for “an opportunity to expose the total incompetence and maliciousness of John A. Macdonald’s administration in the North-West Territories” (Smith’s words). A settler who strove to be a peacemaker “between the aboriginal & immigrant population of the North West” (Jackson’s). A white Canadian who did not believe he was racially superior to anyone.

Smith reminds us that there were individuals in the past who challenged widely held beliefs and the status quo, those who could envisage alternative realities for the new Dominion of Canada. Jaxon was prescient about the importance of Louis Riel, and, perhaps for this reason, the author has dubbed him “a noble visionary.” Smith also insists Honoré Jaxon is not the final word on the man, though it is hard to imagine a researcher discovering any additional archives. He welcomes the way that a new generation of historians have widened the focus of their research, and he points out that history has always been full of opinions.

I don’t agree that Jaxon deserves a “prominent place” in history, as Smith urges. His career is essentially a sideshow, and his antics do not illuminate the realities of authentic Métis communities today. So from that perspective, Smith’s trilogy of books about reinvented individuals does not contribute much to the search for reconciliation. This is still history from the privileged male point of view, even if Long Lance, Grey Owl, and Honoré Jaxon all drew attention to the plight of Indigenous people. Nevertheless, Smith has taken the time to write — and now update — fascinating biographies that humanize the past, in order to explore its complexities.

Charlotte Gray is the author of numerous books, including Flint & Feather: The Life and Times of E. Pauline Johnson, Tekahionwake.