A published writer I know once told me that the minute any of her children takes up a pencil and expresses a desire to write, she will immediately yank it out of their hand. Who would want to encourage a loved one to enter a life filled with anguish, rejection, and hardship? For any would‑be writer who wants to know the truth about publishing, swap out that pencil for Off the Record, a compilation of reflections from Caroline Adderson, Kristyn Dunnion, Cynthia Flood, Shaena Lambert, Elise Levine, and Kathy Page on what “lured them into this writing life,” as the editor of the book, John Metcalf, explains in his foreword.

Metcalf understands the bumpy terrain of Wordsville. A presence in Canadian letters for more than five decades, he has worked with countless authors in his capacity as senior fiction editor at Biblioasis. He’s also completed more than a dozen volumes of fiction and non-fiction himself. His appreciation for the challenges of being a published writer is reflected in the clever approach he takes in Off the Record: asking these six contributors “continuing questions” about childhood, identifying as writers, favourite books, and struggles and triumphs, and then removing the prompts so the pieces read as unguarded narratives that are charming in some cases, disturbing in others. The resulting chapters are not highly structured essays but rather spontaneous outpourings — seemingly off-the-cuff, or as off-the-cuff as anyone who likes sentences can be.

Following each author’s freewheeling commentary comes one of her polished pieces of short fiction. The juxtaposition provides a fascinating glimpse into the mystery of the writer’s craft. If an author’s explanation about how she became a published writer is from the conscious mind, actively pulling up memories, her fiction is from that elusive and all-knowing sibling: the unconscious mind that will make wishes and preoccupations known whether she is aware of them or not. It’s as if two parts of the brain are in conversation.

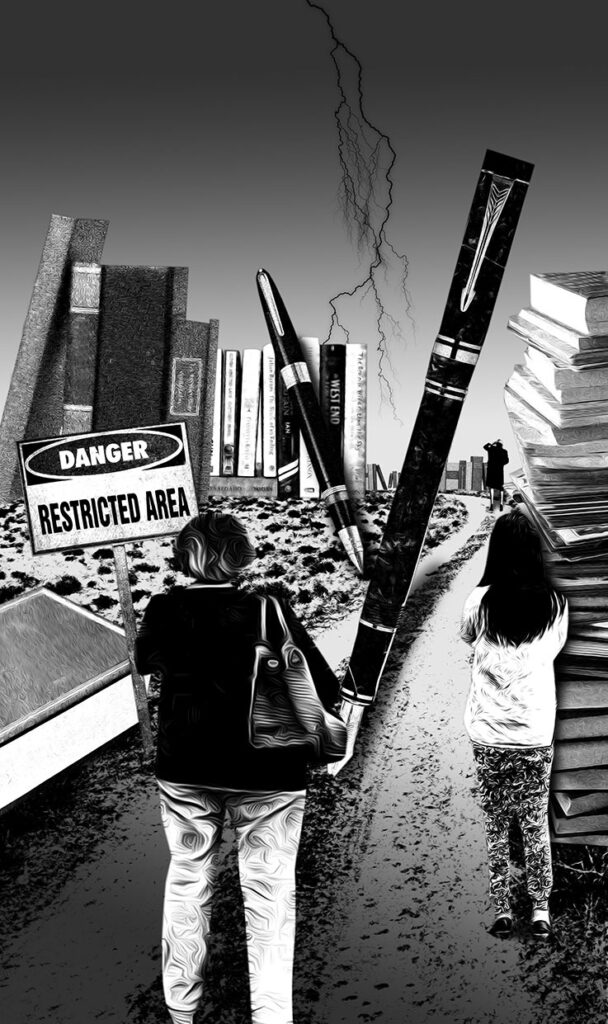

Traversing the bumpy terrain of Wordsville.

Pierre-Paul Pariseau

This dialogue is particularly pronounced in Elise Levine’s section. The novelist and short story writer recalls a terribly painful childhood. “Savagery passed off as love and affection” is how she describes her family life, growing up in Saint John, where the “towering menace” of her mother would brush “her hands over my body, including places she shouldn’t.” As a child, Levine would wish her parents dead. Yet beautifully, paradoxically, her mother liked to read to her and her brother, introducing “the world — whole worlds.” Books were Levine’s salvation and writing her escape: “Transport straight from the desk, where the mundane — the surface with its ugly narrowness, its restrictions — falls away, replaced by a more intense, vivid world.”

Words: they have such power. Levine was not only “wildly attracted to the abracadabra” of them in books as a girl but also hurt by those of her parents: “Shut up, stupid. You dummy.” “Look what you’ve made me do.” “We punish you because we love you so much.” She documents these abuses as though they were said yesterday —and never forgotten.

Then follows “Armada,” about a woman at the gravesite of her mother alongside her father and brother. It is sharp and poetic, and it’s profoundly moving to wonder how Levine’s suffering produced such beauty and to realize that her childhood, horrible as it was, was a gift for her as a writer. The reader sees, in plain sight, that fiction is a mystical and selective transformation of experience.

Other participants in Off the Record present the writing life more pragmatically. The award winner Cynthia Flood, for example, recalls her influences and experiences in a no-nonsense format, with sections titled “Family,” “Elementary School,” “Secondary School,” “Twenties,” and so on. I loved her precise recollection that a highlight of elementary school was learning the words “fallow” and “sallow” on the same day. (Be still, the word-nerdy heart of writers everywhere!) Flood documents her fiction writing in the same straightforward manner, explaining that she starts with “phrases, fragments, single words. By hand. No connective tissue.” Then she shows us how she did it for “Calm,” the story that follows.

Inspired by the sound of four mounted police clop-clopping down a nearby street one October night in Vancouver, the story concerns a boy from an abusive home who escapes into the darkness in order to follow horses that are training for a protest march. Flood opens her notebook so we can read her thoughts as the narrative takes shape in her mind. “A child hears? sees? follows?” she jots down. A few days later: “Add map, mapping — key. How? Boy has to see map showing stables.” Later still: “Do the rider-cops have holsters? Yes.” And “take out street names — all, if poss. Yes.” To read the story in its completion — a spare piece that manages to produce whole scenes in the reader’s head with a few words — is to take a brilliantly compact MFA writing course. Lesson learned: craft can be methodical, not just mystical. “I ask each paragraph and then each sentence, Why are you here?” Flood says of her editing process.

Admittedly, not all the stories in Off the Record made me feel like a chin-stroking shrink, cleverly identifying which shards from childhood and expressed interests poke up through the authors’ fiction. Readers could also find it difficult shifting so abruptly from non-fiction to fiction. But consistently entertaining is each author’s dawning realization about her vocation. Rarely was it a lightning bolt moment; more like a subversive disease, revealing itself through intermittent symptoms — love of literature and observation — until it fully bloomed and could not be denied. Rarely was it glamorous.

In the case of Kristyn Dunnion, the journey to published author involved being “comatose at school, working as a weekend lifeguard, of all things, and cleaning the CPR manikins for extra cash.” (Never underestimate the power of a powerful image.) She grew up queer and sensitive, weeping when “Charlie Brown was picked on by other Peanuts characters,” in a family of six on the shores of Lake Erie. Dunnion’s humour is wry and hard won. She describes a hilarious moment at the University of Guelph when she left some of her comics in the Womyn’s Resource Centre, “hoping to meet chicks,” only to see a special meeting called to discuss “hand-drawn obscenities discovered on the coffee table,” now safely locked away. “My comics! Banned in Guelph!” she crows. They were totally misconstrued, she explains, adding that she fessed up at the meeting and “thanked them as sincerely as possible.” The upshot? “At least I know who not to hang out with.”

Dunnion’s self-discovery as a person and a writer is told with deadpan acceptance and not a hint of regret. There’s no fighting who you are, her section implies. “If a wildly enthusiastic octogenarian tries to sell you one of my books, it’s probably my dad,” she notes. “Being a published author compensates for my confusing pansexuality, for refusing to marry or have kids or drive a car or eat meat, and even for earning so little money.”

With these dispatches, it becomes clear that no path to being a published author is easy or straightforward. It’s particularly edifying to learn that a prolific and award-winning writer such as Caroline Adderson was “completely ordinary” as a child and young woman. A “tussle with cancer” at the age of fifteen turned her into a serious student. She once brought a copy of D. H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers to school to impress her English teacher, who tapped its cover knowingly and told her to be sure to read it again when she could understand it. Later, at the Banff Centre, Adele Wiseman, then director of the writing studio, took a maternal sort of interest in Adderson. In a “desperate attempt to seem arty,” Adderson liked to wear a vintage suede jacket with the collar turned up. Every time Wiseman encountered her student wearing the outfit, she would turn down the collar and give it a loving pat.

Becoming a writer was a matter of “egotism and revenge,” Adderson notes comically, recalling how a cat-hating former roommate doing his doctorate in science once strutted into their shared house, waving around a letter from The New Yorker as though it were a commission. It was merely confirmation of receipt of his pitch about a women’s softball team. No promises made. Adderson immediately thought, uncharitably, “If Roger the Cat Hater could be a writer, so could I.”

For her part, Shaena Lambert describes a wonderful childhood memory of a huge red cedar tree in the forest near the family home in West Vancouver. “This tree was my first love,” she writes. Named Monkey Business, it had perfect notches for climbing and boughs that made a comfortable seat, thirty feet in the air. She could see across the woods and watch her mother from afar. The reader immediately understands that voyeuristic habit of a wordsmith and can imagine Lambert up there, with scraped knees, not knowing what she would later become.

She writes about being influenced by a mother who was an on‑again, off‑again scribbler herself. “Her gaps influenced me as much as her passionate attachment” to the craft. Later, when Lambert was working for eight years in the peace movement, “the desire — the need — [to write] came to me as a feeling of floating above my body, wanting to slow down, and to find a way, no matter how difficult, to speak in my own voice.” There were snags and dead ends, as well as “the Berlin Wall of the Imagination”— a memorable metaphor for writer’s block. “Each novel or story posed its own internal puzzles.” Each needed “its own visitation of something interesting, some flare of light, or multiple flares, outside of my conscious control.” But Lambert persevered, and she remained fully committed to the challenges of each story. At the end of her contribution, she offers up a lovely passage, describing her discipline as “the daily climb into the branches of a tree, which you have been lucky enough all these years to call home.”

The value of Off the Record is that it’s not prescriptive or pedantic. No one gives advice. It’s not conceived as a tutorial or lecture. There are many books that profess to teach writing (Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and on Life; Matt Bird’s The Secrets of Story: Innovative Tools for Perfecting Your Fiction and Captivating Readers; Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft; Jessica Brody’s Save the Cat! Writes a Novel: The Last Book on Novel Writing You’ll Ever Need), but they hold the secrets that worked for their authors, not necessarily for everyone. Embarking on a life as a writer is as doubt-riddled an ambition as pinning down faith in a god. You have to take the journey yourself with few guidelines and no maps.

The authors in Off the Record chart the course of their careers with stories of rejection, bad publishing decisions, punishing reviews, eventual triumph, and formative experiences. Which is the best kind of education for any wannabe writer — and a reminder for readers of the commitment involved in creating the fiction they get to enjoy.

There are some uncanny similarities to these personal stories. The influence of mothers, both good and bad, is one. Kathy Page explains that her writing sprang “from my father’s love of books and my mother’s habit of exaggeration.” Born just outside of London, England, the third of three daughters, she was “encouraged to talk to statues, animals, and imaginary beings of many kinds.” But her mother was also difficult. Page was anorexic as a teenager, struggling with family dynamics. She recalls a fight on the stairs as her mother pushed her up to her bedroom. She refused to go and pushed her mother back down, “our hands buried in each other’s flesh.” Page was flooded with shame. Some mix of the imaginary games they played and that fight on the stairs made her into a novelist, she tells us.

Eventually Page found her way. She followed her curiosity, as if someone had left bread crumbs for her in a forest. At one point, she decided to participate in a writer-in-residence program at Her Majesty’s Prison in Nottingham. None of her friends could understand why she would want to do such a thing. The inmates were lifers — difficult men, uncooperative and violent offenders. But she felt drawn to the opportunity. The rewards were plenty: learning that “the same person could be both kind and cruel, a bully and a victim, and that I could feel pity, horror, and outrage, all at the same time.” The experience informed Alphabet, her novel from 2004.

The differences and similarities contained within Off the Record yield a subtle revelation. It doesn’t matter if you went to private school, grew up poor or gay, endured a dysfunctional family or benefited from a supportive one. The craft of writing unites all authors. We all yearn for that elusive high when the writing is good. A great story “held the breath of ancient mystery,” recalls Lambert. Reading great prose was like “lighting a stick of dynamite inside your head,” Dunnion offers. Who wouldn’t want to experience such a rush? Or at least try?

Sarah Hampson is currently at work on a novel.