How queer is Christianity? In Dayspring, with the help of historical sources and personal recollections, Anthony Oliveira puzzles out the failings of Christianity, and more specifically Roman Catholicism, with regard to queer sexuality. Can queer people recover any spiritual heritage from Catholicism, which has rejected them over centuries with homophobic righteousness?

Dayspring is not a simple work of fiction so much as an anthology, a memoir, an interpretation of the Gospels, and a handbook to queer, or at least post-Christian, spiritual life. It combines Biblical stories with reflections on love, cormorants, kitsch, martyrs, and other topics. Episodes range freely over time to create a fusion of then and now. A first-person male narrator, identified only by the lowercase pronoun “i,” retells the chief events in Christ’s life, from nativity to crucifixion, though not necessarily in chronological sequence. In fact, “i” has a rambunctious, sexual relationship with an unnamed man who has all the characteristics of Jesus Christ and then some.

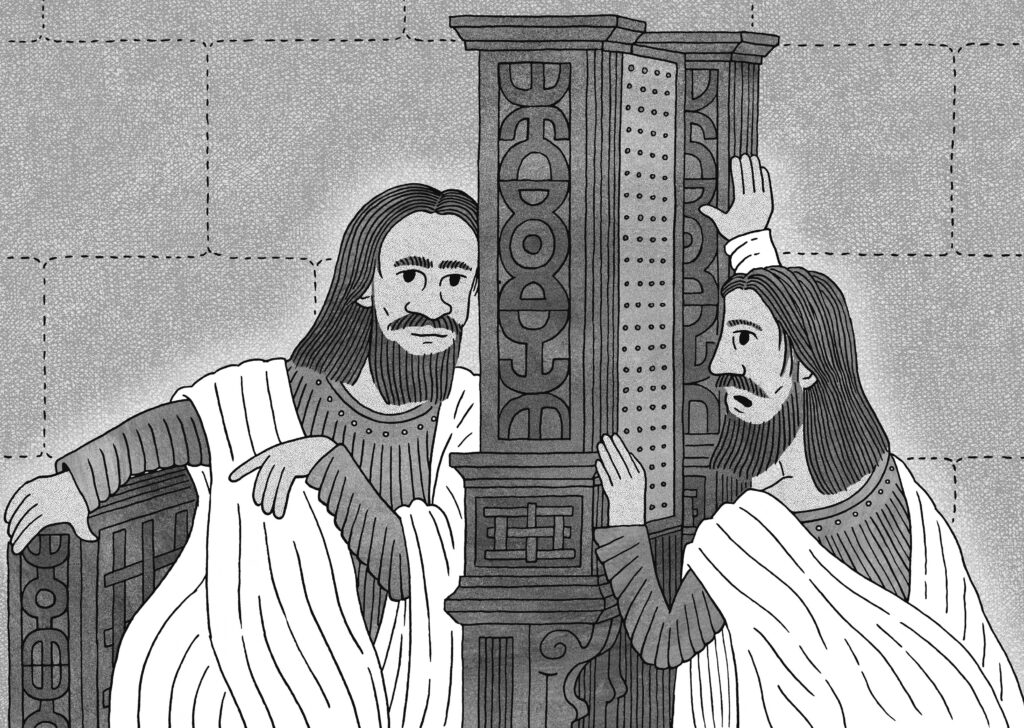

Oliveira extrapolates this queer bond from scripture. According to the Gospel of John, a devoted disciple leans on Christ’s bosom at the Last Supper and, after the Crucifixion, runs to the empty tomb alongside Peter (John 13:23, 20:4). Jesus predicts that this disciple will not die; instead, like a pining lover, he will tarry on earth until Christ returns (John 21:23). In some interpretations, the beloved disciple is said to have written the Gospel and three Epistles of John, as well as the Book of Revelation. Oliveira, who knows this lore inside and out, treats the man as a grieving lover who meditates on endings, beginnings, and the meaning of time.

Confessing plot lines that didn’t quite make it into scripture.

Tom Chitty

On the cover of Dayspring, an eighteenth-century painting of a cupid-lipped Saint John the Evangelist merges with the naked torso of a young man sporting a nipple ring and tattoos. Elegant design characterizes the book. Prose has lineation as if it were poetry, with the dimensions of the page framing scenes, sayings, and extracts from mystical and literary texts. White space allows words to hover on the page; some pages are full, but others bear just a few lines or even just a few words. Toward the end of Dayspring, several blank pages interrupt the flow of words altogether, like a weighty silence after a rumble of thunder. As in the Bible, the speeches of Christ the boyfriend appear in red —“rubricated” is the technical term — to separate them from the language of “i” and other mortals. Some of Christ’s rouged‑up lines follow his Biblical utterances to the letter, but just as often he throws out unexpected colloquialisms, such as “Whew” or “That was fun.” Christ is thoroughly human. He smokes pot. He takes naps. He likes having sex. Sometimes he emits a “thick jock smell.” He has a sense of humour. Sassy in its use of language and surprising in its appropriation of Christian stories, Dayspring is closer to Jesus Christ Superstar or Lil Nas X’s “J Christ” than to the German theologian David Strauss’s The Life of Jesus — and that by a long shot.

The range of references in Dayspring will keep readers on their toes. Oliveira, who holds a doctorate in Renaissance literature, applies his learning deftly to make a case for the queerness of Christianity. Some sources are attributed: Saint Francis de Sales, George Herbert, John Donne, G. K. Chesterton, Bernard of Clairvaux, Robert Southwell, Anselm of Canterbury, Meister Eckhart. Other allusions are unattributed, but they will ring faint bells. Milton’s Areopagitica lies behind a reference to “a fugitive and cloistered virtue,” just as “my name was written in water” is adapted from a line in Shelley’s Adonais. When Christ the boyfriend says, “i had not thought death had undone so many,” he pre‑empts T. S. Eliot, who makes the same comment in The Waste Land. Shakespeare is an abiding presence. Lines from Macbeth, The Merchant of Venice, Richard II, Hamlet, and The Tempest jostle alongside tributes to Joni Mitchell (“paving gehenna to put up a depraved parking-lot paradise”) and the critic Leo Bersani (“the rectum is a grave”). The slogan “An army of lovers will never be defeated” has had several iterations in the wider LGBTQ community, including an ACT UP version popular in the 1990s: “An army of lovers cannot lose.” One of the delights of Dayspring is its playing up and down different registers of language. The high-minded blends familiarly with the crass. The Biblical makes out with the raunchy.

Queer fiction in Canada has a now-you-see-’em-now-you-don’t ephemerality. Rarely do readers think of LGBTQ works as a corpus with a unified purpose. An incomplete list of queerly Canadian fiction might include such pioneering works as Jane Rule’s Desert of the Heart, Scott Symons’s Place d’Armes, and Timothy Findley’s The Wars, as well as such examples from the past thirty years as Shyam Selvadurai’s Funny Boy, Wayson Choy’s The Jade Peony, Ann-Marie MacDonald’s Fall on Your Knees, Dionne Brand’s In Another Place, Not Here, Edward O. Phillips’s Queen’s Court, and Joshua Whitehead’s Jonny Appleseed. Queer fiction in Canada is defined more by the caprices of desire — coming out despite social and familial pressures not to, understanding authentic love objects and feelings — than by its graphic sex scenes. Widely considered one of the foundational queer texts in the Canadian canon, Sinclair Ross’s As for Me and My House features some passionate piano playing and soulful walks along the railway tracks but nothing in the way of conjugal relations between Mrs. Bentley and her husband.

By contrast, Dayspring offers a wide array of queer sex: fierce, tender, recreational, oral, anal, masturbatory, matutinal, nocturnal, alfresco. Having sex with Christ presents complications for the “i” narrator. While giving his lover a blow job, the beloved disciple worries about scraping “god’s perfect cock with my teeth.” On one occasion, during a bonfire with dorm mates, the Christ-like boyfriend pulls the beloved disciple into the dark woods, where, with vigour and variety, they “taste the strange flesh of Sodom.” In the book, metaphors for sex tend to have a slightly Biblical flavour, with many references to spilling seed, as when the disciple relates “how deep into the trench of me he has rutted his seed.” In many cases, the disciple remembers these erotic encounters with a monumental sense of loss: “you left me and i ache like an uncracked knuckle to hike down your ratty sweatpants and kiss the constellation of moles crushed under your waistband above your thick black bush and take the whole of you unwashed from the wastes into my mouth and i knew and know that i am lost to this to you forever.” Whereas the beloved disciple squirms when others notice him as a queer man —“i was just your faggot now,” he remarks at one point — Christ the boyfriend, who is a compound of many boyfriends and many acts of sexual congress, never expresses shame or unease about his queerness. God is love, in all its forms, and all things of the body are clean.

In Dayspring, sex is both sensual and ecstatic, recalling the saints who describe their love for Christ in orgasmic terms. In one quoted passage, Saint Teresa of Avila has a vision of an angel holding a spear that he suddenly thrusts “over and over, through my heart, penetrating / me to my bowels. And when he drew out the spear he / seemed to draw them with it, leaving me on fire, with / a wondrous love for god.” In defence of this overtly sexual imagery, Oliveira quotes Simone Weil, who declares that mystics describe their union with God in terms of sexual love because that is the medium in which mystics work; to reproach them for their suggestive metaphors would be like reproaching painters for making pictures out of pigments.

The aesthetic of Dayspring is baroque: excess is one possible route to godliness. If spiritual fulfillment is not available via reason, it might be grasped via the body and its capacity for ecstasy. Yet this belief in sensuality as a way of knowing might be misplaced. Feeling “a wondrous love for god” might be merely erotic longing and nothing more. Mary Magdalene, as a woman with some experience of sexuality, cautions the beloved disciple about believing his boyfriend is divine: “plenty of dudes are gods / in my experience it doesn’t end great for their fuck buddies.”

“Dayspring” is an old-fashioned synonym for “dawn” or “daybreak.” The homoerotic content of Oliveira’s book may not herald a new day for queer Christianity, but it does make the morning after worthwhile. While some readers will castigate it as blasphemous or dismiss its queer sex as pornographic, that prudish attitude would miss the point entirely. Dayspring is really about what queer people might be able to salvage from Christianity — as a legacy, as a spiritual domain that is scripturally and exuberantly queer.

Allan Hepburn is the James McGill Professor of Twentieth-Century Literature at McGill University.