Canadians of a certain age may remember when schools released cookbooks. Recipes were drawn from the student body, teachers, and parents, with the collected results then sold to raise funds. My elementary school in Gladstone, Manitoba, released a few during my time there, and I still have one, Gladstone Elementary School Recipe Book, from 2004. Inside are such culinary nightmares as “jellied cabbage deluxe,” “creamed cucumbers,” “burpless onions,” “taco quiche,” “microwave manicotti,” and “pizza schnitzel.” What to make of this nauseating mishmash?

“These recipes,” my principal wrote in his introductory message, “are representative of the variety of cultures found in our community.” The word “variety” in this case was doing a lot of heavy lifting: “Japanese chicken wings,” “Danish meatballs,” “Baja lasagna,” “Applebee’s Chinese salad,” “Aunty M’s chop suey,” “Land of Nod cinnamon buns,” and “beef international.” But you can be assured that the authors of these dishes were not as cosmopolitan as the titles may suggest. With few exceptions, they were white prairie folk who ate white prairie food, all of them embodying a commitment to speedy preparation and refined sugar.

There were, back then, six places to eat out in Gladstone, which wasn’t bad for a town of 1,000. The options included two greasy spoons, a bakery (“Get yer buns in here” was its slogan), the golf clubhouse, a drive-through on the highway, and a Chinese restaurant called the Paris Café, which stood so close to the rail line that when a train passed, the cutlery would rattle, unattended chicken balls would roll across the tables, and the swinging paw of the maneki-neko cat would adjust to a new rhythm.

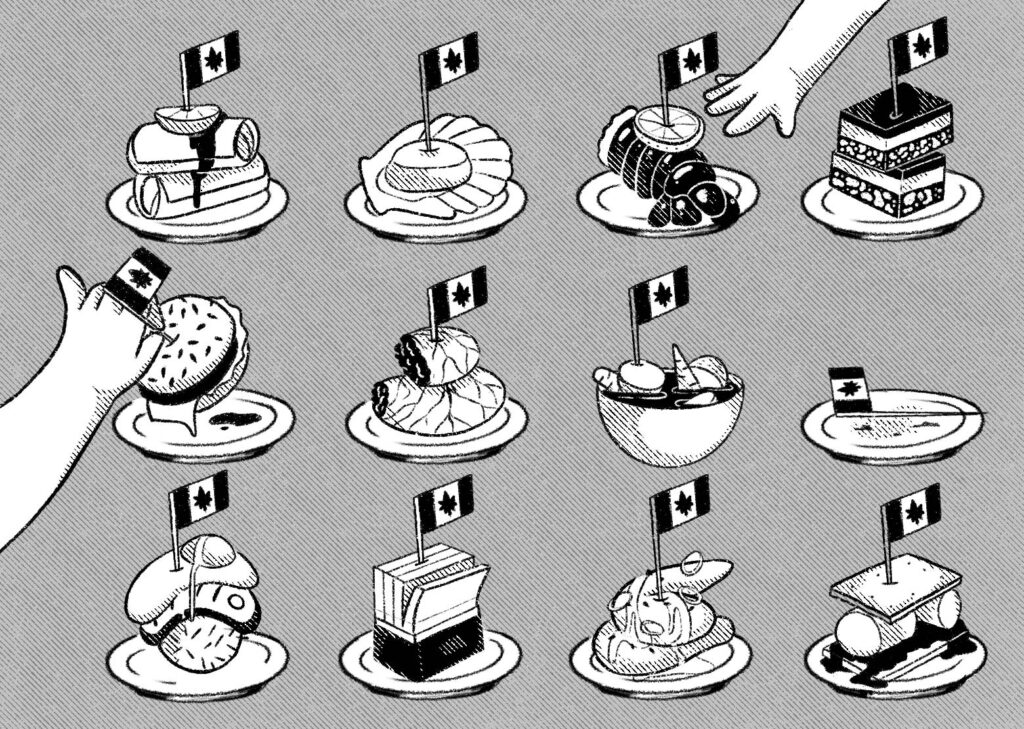

Sampling the many dishes that constitute a national cuisine.

Tessa Presta

The intervening twenty years have seen one restaurant burn down, the bakery shuttered, and the arrival of Tim Hortons. Another significant shift in my hometown’s food scene came with the influx of Filipino migrants, who brought investment along with adobo stew. McKinley’s Supermarket became Vego’s Kitchenette, which offers sweets and treats of the Philippines, like taho, paksiw, and puto calasiao. The area butcher shop also traded hands and now sells lumpia and pork tocino alongside chuck roasts and beefsteaks. If my alma mater produced a cookbook today (if such things are still done), it would reflect a different town altogether, one with a different concept of variety.

It is progressions like these that Mmm . . . Manitoba is all about, using individual stories and historical records to chart the presence and changes of cuisine in the Keystone Province and trying to discover what, if anything, our food is. Kimberley Moore and Janis Thiessen, both professors at the University of Winnipeg, travelled near and far in the summers of 2018 and 2019, often with a food truck, inviting Manitobans to tell their food stories and cook up a recipe or two. In Dauphin, they found Ukrainian perogies and holubchi; in Steinbach, it was Mennonites melding German noodles with barbecue. They talked to cookbook authors and chefs, from Churchill to Winnipeg, one of whom, Steven Watson, is committed to making meals primarily from ingredients that could be found in Manitoba before Europeans arrived.

Mmm . . . Manitoba is the book component of the Manitoba Food History Project, which also includes a podcast and a website where interviews, stories, maps, and recipes are collected. Those interviews are unpolished and colloquial, but the sense is that, as they ate their way across the province, Thiessen, Moore, and their colleagues were having a damn good time. Who wouldn’t, when sampling slow-roasted bison with burned sage, Ichi Ban cocktails, or snow goose tidbits is part of the job?

As I read their book, the definition of Manitoban and Canadian food nagged at me. Inspired by Moore and Thiessen, I sought help with the definition by asking around. “Ketchup chips,” my sister in Victoria said, revealing her (our?) debilitating junk-food addiction. “All-dressed chips, Nanaimo bars, Coffee Crisp, Caramilk, and Caesars,” she continued. People I know in Nova Scotia variously came up with lobster, scallops, hodgepodge, Beaver Tails, poutine, and blueberry grunt. A second-generation Ukrainian friend who had me over for dinner answered, simply, “Cabbage rolls.” A German visitor to Canada pointed to s’mores, while an Australian tourist said, “Just generic North American tucker.” On a visit to Churchill, I put the question to a young lady from Sanikiluaq. “Oh, muktuk!” she replied, with reference to beluga blubber. “Raw’s good, but I love it fried.” I wanted to try it and asked her to get me some while I was in town, but it never turned up — difficult to procure, it seemed.

“Meat and potatoes,” my father the beef farmer said, while declaring a preference for a nice pork roast. “Hot dogs and hamburgers,” explained my English-born mother, who mostly prefers salads and other things that are meant to help one live forever. “But are you saying Canadian food or what people actually eat?” she asked. In other words, one answer is theory, the other is fact.

That global institution of fact and data, the United Nations, listed in its 1967 cookbook Canada’s national recipes as cod soup, tourtière de la Gaspésie, beefsteak pie, sucre à la crème, butter tarts, and blueberry crisp pudding. Such variety sounds a lot like indecision. Hamlet could never make up his mind, either, and described himself as subsisting on “the chameleon’s dish” and “the air, promise-cramm’d.”

While their project makes for an interesting look at what meals are being served in Manitoba, Thiessen and Moore seem to acknowledge that answering “What is Manitoban/Canadian food?” is as difficult as separating out the flour, sugar, and eggs from a fully baked cake. They dither over whether Indigenous cuisine should be the baseline of Canadian food, but they stop short of making a definitive statement: it’s too political, too cultural, too nationalist a claim. They over-worry that certain foods are ethnicized, racialized, or flattened by culinary colonialism, but that is the very nature of cookery: an experimental mathematics that produces something more or less than the ingredients. Their fair rebuttal is “Why are you asking that question?”

Indeed, the question seems to belong to another time — before lumpia could be bought in Gladstone, for instance — and subverts the notion of the Canadian melting pot, where, presumably, we are all reduced to a dense, indistinct goo.

Yet food is territorial and engenders strange feelings of ownership and proprietorship. Even Thiessen and Moore are not immune. In a chapter devoted to Winnipeg’s drive-through culture, they plant a proprietary flag on Fat Boys and Nips: two burgers originating in town, the former topped with chili, the latter the signature of the local Salisbury House franchise. “These are ours,” the authors write, implying that Fat Boys and Nips made in Los Angeles or Toronto are imitations, that the real thing can be had only in Winnipeg.

These feelings aren’t easily understood. Can a people “own” a burger? Is food something around which Canadians need to form an identity? Thiessen and Moore hold up the Fat Boy as something that can make Winnipeggers proud amid a “perceived lack of national status in the geographic centre of Canada, and negative headlines that declare us frigid, racist, or impoverished.” Yet I have doubts as to whether a sauced‑up patty can unite the city, especially as Thiessen and Moore posit that the “question of authenticity is also a racist one.”

Food can be linked to national identity, but it doesn’t need to be, especially not in Canada, where it seems to provoke our unique brand of mortified jingoism. It is, however, irrefutably linked to memory and work. A meal in this country never springs from nowhere. I found a good example of this fact in LaHave Bakery. Told in alternating snippets by the proprietor Gael Watson and a cadre of co-workers, friends, family, and community members, this book is the charming tale of a shop on Nova Scotia’s South Shore. The story of these entrepreneurial and enterprising women is more engrossing than it might at first seem, with its behind-the-scenes look at what it takes to build a successful food business in Canada. Watson’s forty-year journey, from buying a dilapidated outfitter on a wharf to turning it into a lodestar bakery-cum-grocery-cum-bookshop, reads like a particularly Canadian tale, with its emphasis on civility, honesty, shopping local, and seeing potential in wackadoo ideas. The recipes don’t hurt either.

LaHave Bakery offers a different kind of narrative than that of Mmm . . . Manitoba, one that is less academic, less abstract. Watson’s statements don’t dither in intellectual purgatory: “Eating with a conscience is just an extension of living with a conscience,” for example, or “You don’t have to know everything about something, but you need to be able to trust what you’re eating.” When someone questions the tradition of her “traditional” bread, her reply reminds me of many culinary Canadians I know — not apologetic, but self-assured: “My only answer to that person was, ‘It’s traditional to me.’ This is my tradition and almost forty years later, it’s become a tradition for all the little babies who started eating the bread and grew up with it.”

The book is like an ode to elbow grease, no doubt the most venerated Canadian ingredient. Of the LaHave Bakery, one employee says, “We have to do it the long, hard way so that it’s ethical and good.” That is how Canadians see their food: hard-won, unanalyzed, personal. That is the iron edge we are comfortable with, happy that our need to be accommodated is overruled by our desire to be useful, practical, uncomplaining.

There may not be any particular Canadian food, but there is a way of eating that is distinctly Canadian: the potluck. Variety is our life-spice, and we’re better for the gathering of different foods, so that we can try a little of this, a nibble of that. I’ll bring the beef international.

J. R. Patterson was born on a farm in Manitoba. His writing appears widely, including in The Atlantic and National Geographic.