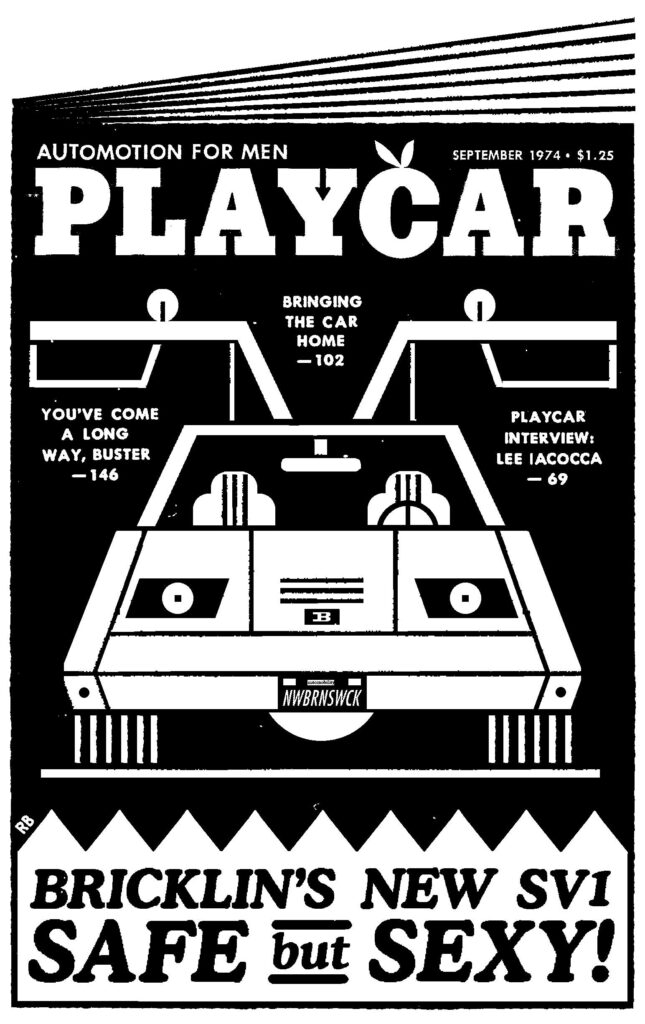

Here is a history book with a personality as offbeat as its subject: the futuristic and ill-fated Bricklin Safety Vehicle‑1 sports car from the 1970s. Dimitry Anastakis has authored other works on the Canadian auto industry, but none are as epic — or as playful — as Dream Car. Its scholarly bona fides are striking; almost 100 pages of endnotes and bibliography attest to the seventeen years the University of Toronto professor spent on the project. Yet it’s far from stodgy. From neon-tinted cover art to a car-song playlist, from dozens of vintage photos and ads to an invitation to read its seven chapters out of sequence, Dream Car evokes a mind determined to wash some of the starch out of Canadian history.

What better tone to strike than playfulness in a book about a car that was essentially a toy for boys? With its long, tapered snout, hideaway headlights, big V8 engine, moulded acrylic body, electro-hydraulic gull-wing doors, built‑in roll cage, side-impact guardrails, and energy-absorbing bumpers, the two-seat Bricklin was hardly meant for hauling the kids to soccer or carting the groceries home. Conceived as a safer alternative to beasts like the Corvette Stingray and the Dodge Challenger, the car was as testosterone-supercharged as its namesake promoter, the high-flying American entrepreneur Malcolm Bricklin. (How supercharged? A reproduced promotional photo shows an SV1 parked with its doors opened provocatively as a geyser in the background erupts in suggestive glory.)

Fewer than 3,000 were built during two years of problem-plagued production at plants in Saint John and Minto, New Brunswick, before the company went bankrupt in 1975. Which raises a question: How could the story of a car that’s not much more than a footnote in the annals of automaking inspire an effort on the monumental scale of this book? Anastakis argues that the Bricklin endures as a cipher for “the evolution of the automobile and its impact across North America’s twentieth and twenty-first centuries and on ideas about the future, technology, entrepreneurship, risk, safety, showmanship, politics, sex, gender, business, the state, and the industry’s birth, decline, and rebirth.”

A playful tale of Canada’s auto industry.

Raymond Biesinger

Two principal players animate the saga. Malcolm Bricklin, a safari-suited “machismo sex symbol,” was not content to have made his first million in the hardware business by the time he was twenty-five. He dreamed of being a player in the big leagues of American commerce, and there was none bigger than automaking. Through guile and abundant chutzpah, he assembled the financing, expertise, and infrastructure to develop the SV1, the first model to be produced by a new North American auto company since the 1940s. His improbable fellow dreamer was Richard Hatfield, the high-living, closeted New Brunswick premier, who bet a boatload of public money on a magic bullet that would transform his have‑not province. That the $23-million scheme flopped prompts murmurs to this day. “Had the dream of the Bricklin just been a show, a fantastic performance by the two men?” Anastakis asks. “Had it all just been a con? And, if so, who, exactly, had been conned?”

Anastakis is inclined to give both men the benefit of the doubt. The venture failed mainly because Bricklin’s reach exceeded his grasp. For his part, Hatfield couldn’t afford the political cost of dipping ever deeper into the public purse; he had no choice but to pull the plug as production snags and cost overruns mounted. And all of this was playing out in a climate of tectonic change. Automobile industrial modernity — the “almost complete recreation of society by the car and its use” that peaked in the 1950s and ’60s — was giving way to a postmodern order triggered by the OPEC oil embargo, runaway inflation, deindustrialization, and social trends like feminism and gay liberation. Smaller, more efficient, and more affordable Japanese cars (including the Subaru, which Malcolm Bricklin introduced to North America in 1968) that were once scorned were emerging as the new auto-buying paradigm. Into this flux arrived an expensive (about $80,000 in today’s money) plaything that flaunted hetero masculinity. Despite basking for a brief moment in the media sun, the Bricklin was already a relic as the first ones rolled off the assembly line.

But as a vehicle for exploring the argument that the automobile was the “key animating cause and consequence of how we understand the one and half centuries of North American history from the 1890s to the 2020s”— automobility, for short — the Bricklin rocks. The volume of material Anastakis covers to support his case risks overwhelming the average reader, but the polish and affability of his prose render the narrative remarkably easy to digest.

It’s not until his acknowledgements that Anastakis reveals some personal history that helps to explain why he unpacks the story of the Bricklin on this scale. Anastakis is the son of Greek immigrants who settled in the Toronto suburb of Agincourt in the early ’70s. Like countless suburbs elsewhere, Agincourt was a poster child for automobility. The car was king. Everyone had one — or more — except the Anastakis family. The driveway in front of their townhouse was empty until Anastakis’s mother got her driver’s licence in 1979 and bought a used station wagon. Looking back, Anastakis suspects that growing up carless in an auto-addicted place helped foster his ideas about the ubiquity of the automobile. His “early distance from automobility, which necessitated observation of the car’s influence, probably explains why I see the condition of automobility the way I do,” he writes. “Automobility has always been more than a simple academic pursuit; the car was something that had, in its own formative power, pointedly forced me to understand the world in a particular way.”

Dream Car launched in Toronto this past spring. Malcolm Bricklin, in his mid-eighties and long past his Burt Reynolds phase, flew in for the occasion and took the opportunity to promote his latest hustle, a three-wheeled EV he claims will be cheaper and more efficient than what’s currently on the market. Like the Bricklin SV1, it also bears his name — and sports the same distinctive doors. Anastakis must have smiled inwardly as Bricklin expounded on this and his other ventures in the car business for more than an hour. Understanding the world in the particular way he does, Anastakis appreciates the power of automobility to fuel dreams — dreams that apparently die hard.

David Wilson edited The United Church Observer from 2006 to 2017.