In Constructing a Nervous System, Margo Jefferson writes that “memoir is your present negotiating with versions of your past for a future you’re willing to show up in.” The filmmaker and author Chase Joynt opens a chapter of his memoir, Vantage Points, with those words. They help capture his own process of grappling with his childhood, which included years of sexual abuse from his maternal uncle, whom he dubs X. “When I attempt to map my experiences with X into sequence,” he writes, “I am left only with a series of snapshots and scenes that ever evade organization into a clear chronological record of our relationship.” Wading through a collection of memories, half-truths, and archival traces, Joynt faced the challenge of distilling a coherent narrative from a traumatic past. Vantage Points is a moving portrait of his effort to put the pieces together. When he happened upon Marshall McLuhan in his family history, he found an unexpected way in.

Most widely known for coining the aphorism “The medium is the message,” the concept of the global village, or perhaps even his cameo in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall, the University of Toronto professor remains embedded in our cultural and theoretical landscape. After Joynt inherited a box of archival material belonging to his maternal grandfather, in which a newspaper clipping revealed that his great-grandfather married a McLuhan in 1914, Vantage Points began to take shape. The famous name on Joynt’s family tree was incidental, but he seized on its appearance as a way of exploring how his childhood experiences in suburban Ontario influenced his relationship with maleness and trans subjectivity. “Where McLuhan saw the production of media,” Joynt writes, “I see the production of masculinity.”

A multi-faceted approach to life writing.

Jamie Bennett

Vantage Points is the culmination of this dialogue: a slim book organized into sections that mirror the structure of McLuhan’s Understanding Media, from 1964. Joynt considered McLuhan’s various chapter subjects (television, photography, games, and so forth) and mined his own past accordingly. He situates his first memory of X abusing him with reference to Sarah McLachlan’s Fumbling Towards Ecstasy. The album, which played while the assault took place, becomes a temporal reference. “If it weren’t for McLachlan,” he writes after discovering that the record was released in 1993, when he was twelve, “I would have guessed that I was eight.” Here and throughout, Joynt considers McLuhan’s ideas alongside the media of his childhood, a technique that allows him to excavate difficult memories and chronicle events in ways that resist conventional narrative form.

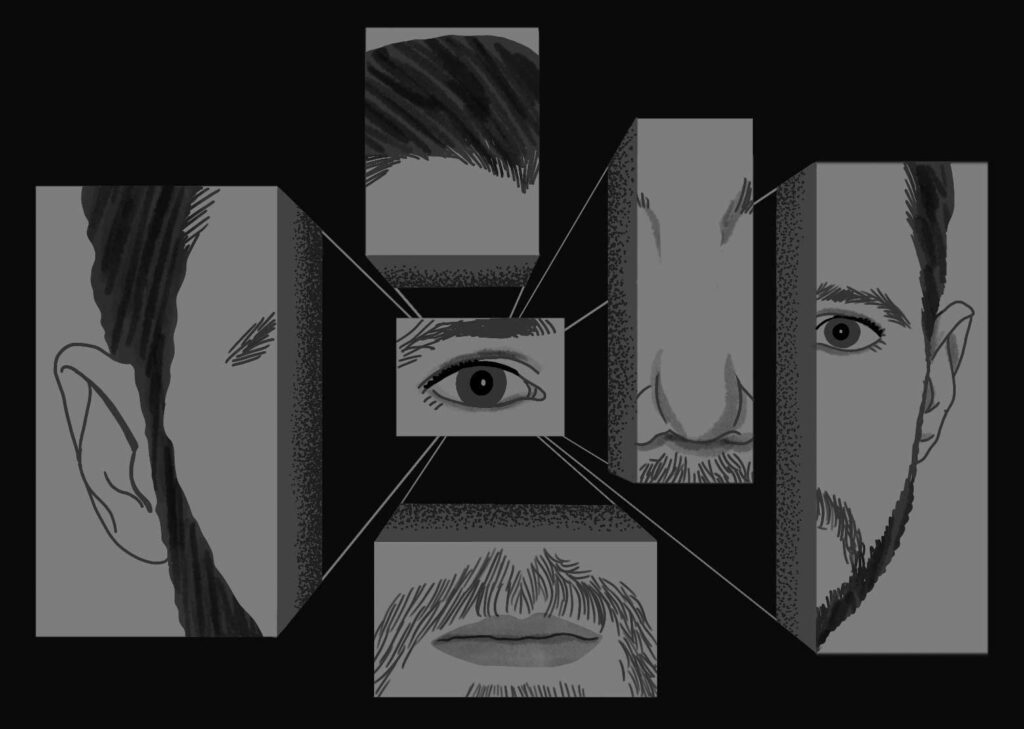

Drawing from his background in visual culture, Joynt has created a multimedia approach to memoir, which layers vignettes of text with photos and abstract illustrations. Attending to the generative space that exists between these different forms, he invites the reader to participate in the creation of meaning. Anchoring his project in early film theory, he invokes cinematic forms of expression “by employing memoir by way of media montage as a method.” Much like the Soviet filmmaker Lev Kuleshov, who is known for showing the influence of juxtaposition through montage (and is referenced in a prologue), Joynt emphasizes the interpretive role of the audience, who contribute emotional depth through their subjective response. This conversational dynamic impresses upon the reader that the book is a live object with the capacity to shift depending on one’s perspective.

Black and white illustrations decorate the pages (a discussion of typewriters opens with a page of retro typeface, for example). Occasionally they produce impactful moments, such as when the author describes a small photograph of his late grandfather as a child (who would become another abusive man) and pairs the passage with a black rectangle of the same size. By withholding the picture, Joynt complicates the literal association between words and images, rejecting the reader’s curiosity as well as the pressure to provide accuracy and detail when cataloguing the past.

Photographs lend another compelling visual dimension. Archival snapshots of relatives are scattered throughout the text, but Joynt never identifies them or provides additional context. At one point, he meditates on Roland Barthes’s concept of the “punctum,” or “the wounding capacities of the image.” With his own strategic use of photography, he shields the wounding capacity of these personal images from scrutiny, while also invoking their emotional potential. Every image — or black box — becomes a site of speculation; the shadowed face of each anonymous man remains an open question.

Joynt underscores the significance of positionality. He questions his own vantage point — and that of the reader — by imagining how someone else might interpret the “press clippings, publications, and exhaustive headshot photography” kept by his great-grandfather. But the importance of perspective is perhaps most acutely felt toward the end of the memoir, in a letter addressed directly to X: “Do you recognize yourself in these pages?”

Vantage Points is a kaleidoscopic gathering of fragments — traces of truth and memory — that extend outward to the reader. With this expansive, shared approach to form, Joynt encourages an ongoing collective project of reaching back into the past to reorient the present.

Alex Trnka is an editor living in Toronto.