Tossed about by the waves of corrupt politicians, a $100-million deficit, collapsing fish prices, and global economic depression, Newfoundland abandoned ship in 1934, relinquishing nearly eighty years of responsible government. A royal commission determined that the British dominion needed “a rest from politics” and recommended instead a commission of government, appointed by and responsible to officials in London. The United Kingdom undemocratically assigned governors to administer the commission until 1949, when Newfoundland joined Confederation as Canada’s tenth province.

Out Here, edited by Melvin Baker and Peter Neary, collects the letters and quarterly reports sent to the British secretary of state for dominion affairs by Sir Humphrey Thomas Walwyn, the vice-admiral who served as governor in St. John’s from 1936 to 1946, a ten-year span representing one of Newfoundland’s most transformative periods. The influx of American and Canadian troops during the Second World War lifted the island from its debts and into a $40-million surplus. With an improved economic outlook — and the presence of several U.S. bases — Ottawa saw the strategic advantage of welcoming Newfoundland into Confederation. Walwyn’s letters are illuminating not only because they reveal the inner machinations of the commission of government during this time; his candid tone (described as “racy” by the Dominions Office secretary Alexander Clutterbuck) also provides readers with an intimate diary of political life that one wouldn’t expect from a Royal Navy officer turned bureaucrat.

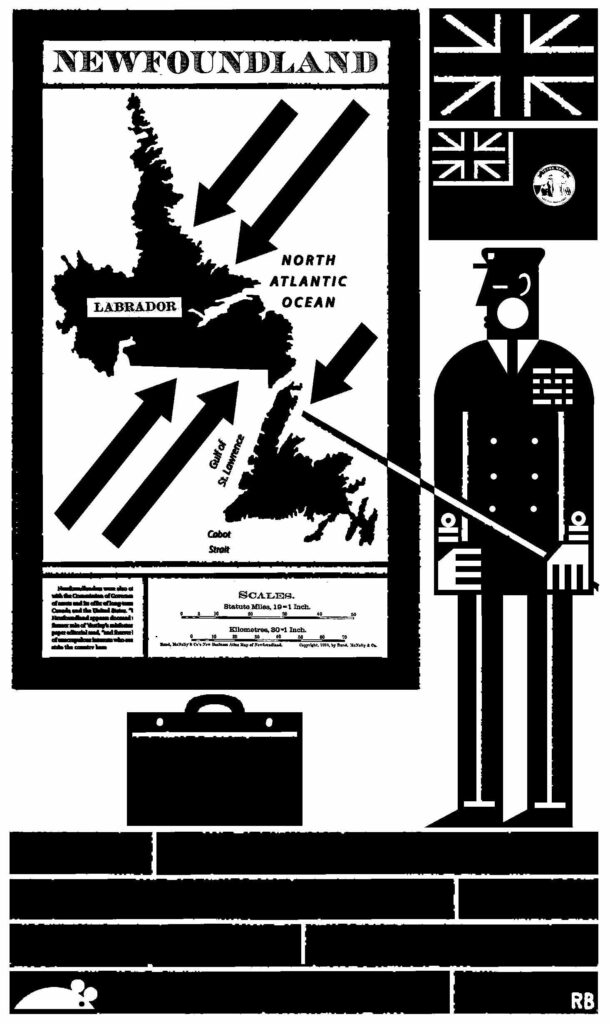

Whitehall’s man on the Rock.

Raymond Biesinger

Walwyn took up his post at the age of fifty-seven. His first report back to London, from April 1936, suggests how dire Newfoundland’s economic condition was at the time. Nearly one-quarter of the population was receiving social assistance, and in some regions the rate ranged from one-third of the population to nearly half. Hitting the ground running, Walwyn wasn’t content to sit in Government House poring over statistics. He travelled to outports and other rural communities and recorded first-hand accounts of life there. “The poorer the people, the more inaccessible the place, the greater the welcome,” he noted. “The warmth of the welcome extended was offset by the deterioration in the general conditions of trade and employment throughout the country,” however, which made Walwyn realize “how slender a margin for prosperity we are endeavouring to rehabilitate this country and how little is needed to hinder if not undo much of the good work achieved.” Walwyn’s wife, Eileen, was also active on the ground, supporting the Newfoundland Outport Nursing and Industrial Association, the Society for the Prevention of the Cruelty of Animals, and the Child Welfare Association, among others.

One cannot help but detect a whiff of imperial condescension in Walwyn’s letters. “I like the people immensely, and we have at once clicked with them,” he remarked. “They have rather an inferiority complex but welcome being dealt with in a friendly way and respond accordingly.” He often lamented Newfoundlanders’ learned helplessness, writing that “it was somewhat depressing to note that the continued failure over a number of years and the hardships and deprivations involved by that failure has demoralized the poorest fishermen to such a degree that they have relapsed into a state of apathy and idleness.” Such persons, he continued, believed that it is “the duty of government to provide a means of living for them.” Yet Walwyn also expressed frustration with “the tendency of the Newfoundlander to drop one occupation and rush to another, especially if the prospects of remuneration, even if limited to a short period, are better.” Many contemporary Newfoundlanders will recognize in these comments a long-standing history of their “betters” pushing and pulling them between places and industries.

When asked how locals would react if the commission of government were prolonged, Walwyn replied that “the majority of thinking people would heave a sigh of relief,” though he qualified his response by saying that “many of these would write to the press and say how the country had been deceived and been given a raw deal.” It becomes increasingly apparent that what Walwyn and other “thinking people” agreed would be the best option for the island was a “halfway house” of a continued commission of government but with more local representation. This smug attitude is what caused many to chafe under the arrangement, even though it may have provided better leadership than responsible government.

Newfoundlanders were also often frustrated with the commission of government’s handling of assets and its offer of long-term land leases to Canada and the United States. “Unfortunately, Newfoundland appears doomed to continue its former role of ‘destiny’s misfortune,’ ” one newspaper editorial read, “and forever to be the football of unscrupulous interests who seem prepared to strip the country bare regardless of the consequences.” Later natural resource projects, including the Churchill Falls contract made under Joey Smallwood in 1969, would prove that control over Newfoundland’s riches was not an issue unique to the commission of government.

It would be unfair to reduce Walwyn to nothing but an elitist apparatchik. In 1945, he toured a cordage factory where employees were earning twenty-five cents an hour and working twelve hours a day. “They seem quite happy and it is quite a family affair,” he wrote sardonically; “one man has twelve children working there, and I am told they all have T.B.” He took personal action by requesting the Labour Relations Officer to investigate the “well-equipped establishment.” He also pushed back against his superiors and advocated for a 30 percent increase in pensions for Newfoundland veterans who had served in the First World War.

Interestingly, Walwyn initially underestimated the impact the Second World War would have on Newfoundland. In a report from 1939, he wrote, “There are however tendencies in certain directions to take things too lightly, to expect an immediate boom in fish and other commodities.” The influx of American military personnel and infrastructure projects offered opportunities previously unheard of. For instance, in Pleasantville, an area in St. John’s near Quidi Vidi Lake, the U.S. acquired nearly 200 acres to build Fort Pepperrell to accommodate 3,500 troops and over 14,000 square feet of warehousing. Nearly 5,000 residents were employed to work on the army base. There were significant projects outside of the capital as well, in places like Placentia and Stephenville. By 1944, wages for labour were as high as sixty cents an hour, over double the rates in 1939, when they were twenty-eight cents an hour. In fact, the wages for labour around American military infrastructure projects were so enticing that many were “leaving their fishing boats and gear to deteriorate.” Walwyn was very pleased that “business conditions throughout the country are so prosperous that all ideas of responsible government have been shelved, at least for the time being, and the Commission of Government are enjoying a little wintry sun of popularity.”

While Newfoundland appreciated the injection of capital during the war, there were some tensions between the locals and the come from aways. Families in Placentia, for example, along with three cemeteries, had to be moved in the middle of winter with little notice to give way to the American military. There were also incidents of Canadian sailors facing charges of assault, drunkenness, and rowdiness while on shore leave in St. John’s. Walwyn lamented that “if they only had a decent bar with a sawdust floor, a fire, and a gramophone, where a man could have a drink and go out, all would be well, but this sadly out of date and self-righteous community won’t accept that.” (It is unfortunate we cannot ask Walwyn for his opinion on the current state of George Street.)

By the end of the war, the “thinking people” were entertaining confederation with Canada. “There is a feeling of alarm that the baby is now being handed to them and they don’t know how to handle it,” Walwyn reported. But despite his occasionally condescending comments, the governor remained popular and left Newfoundland on good terms. The Daily News, which Walwyn had once described as having “no policy other than to blackguard the government,” had this to say at the end of his term: “No occupants of Government House have ever identified themselves so closely and intimately with the life of the people as Sir Humphrey and Lady Walwyn.” After ten years of service, the couple retired to the austerity of postwar England, and Newfoundland, following two years of bitter politicking, joined Canada.

Out Here may be too deep a plunge for casual readers looking to dip a toe into Newfoundland history, but for those eager to really understand the Rock, it is an essential volume. Neary and Baker provide an excellent introduction that contextualizes Walwyn’s governorship. Moreover, the letters and reports are exhaustively footnoted, expanding on people, places, and events that Walwyn mentioned in passing. The text is also supplemented by scores of photographs from the period. For Neary, who previously published a collection of letters from Walwyn’s predecessor, Sir John Hope Simpson, Out Here is a fitting capstone to a distinguished career as one of the province’s great historians. He died in March 2024, just months before the book’s publication.

Brad Dunne is a writer and editor in St. John’s. His latest novel is The Merchant’s Mansion.