I have long been enamoured of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories about Sherlock Holmes and his faithful companion, Dr. Watson. A vocation in which one could use intelligence, reasoning, logic, and the art of disguise to solve perplexing mysteries and earn a living — it has always seemed to me like a dream.

“It is an old maxim of mine,” the famous sleuth says in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, “that when you have excluded the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” What’s certainly true — and not at all improbable — is that many others have fantasized about walking in Holmes’s fictional footsteps. One Canadian, Nicholas Power, may have actually tried. His logic and deductive reasoning seemed impeccable. His ability to crack cases was almost uncanny. Power’s role in saving a high-ranking member of the British royal family earned him international esteem, so much so that the New York Times noted his death, on October 2, 1938, at the age of ninety-five. But was he a real-life Sherlock Holmes, as some newspapers maintained, or something closer to the latter’s nemesis, Professor Moriarty?

What a vocation!

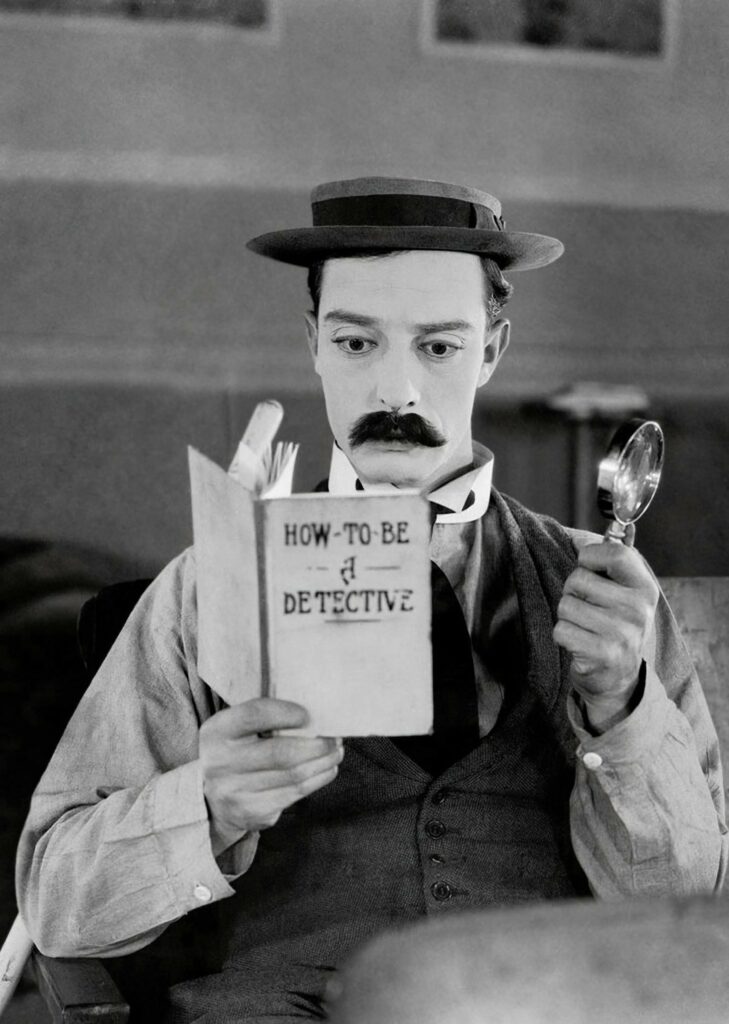

Sherlock, Jr., 1924; Alamy

With The Bad Detective, the journalist Bob Gordon examines how one of Canada’s first police investigators built an undeserved standing as a larger-than-life gumshoe. “The basis of his fame, the foundation myth that his reputation has rested on into the 21st century, is exactly that, a myth,” Gordon writes of Power, whom he depicts as a nineteenth-century peddler of misinformation. “Canadian newspapers were far more willing to print ‘fake news’ than anything media outlets are even accused of today,” he explains. “And, on the other side of the fence, Detective Power was willing to twist his answers and grant his interviews in order to try a case in the court of public opinion long before the legal system ruled.” The result was a “mutually beneficial relationship with both sides lying freely when it suited their purposes.”

Despite his renown, Power was actually a bad detective, Gordon maintains. And his error-filled actions “had evil consequences” that “destroyed the lives of innocent people, allowing the guilty to run free and heinous crimes to go unpunished.”

Born on June 11, 1843, Nicholas Power lived his entire life in Schmidt’s Ville, just south of the Halifax Citadel. (Today, the heritage district is known as Schmidtville.) His father, Patrick, was a mechanic, and his family was Irish Catholic, but little else is known about Power’s early life. He did spend four years in the Royal Navy, working as a butcher boy on HMS Nile, though there is no record of him on the ship during its ceremonial 1863 visit to New York City. In April 1864, Power married Mary Jane Sheehan at St. Mary’s Cathedral, and he left the navy shortly thereafter. When the Halifax Police Department was established that fall, the twenty-one-year-old veteran was hired as a constable.

Power made a splash in late October 1883, after he uncovered an apparent conspiracy to murder Prince George, second son of the Prince of Wales. He had been investigating a burglary when he came across two names in the Parker House hotel’s register: William Breckton and James Holmes. “They were American, from Boston, with Irish-sounding, probably Roman Catholic names and potentially Fenians,” Gordon writes. Power searched their room and found a valise containing dynamite, fuses, an alarm clock, and “all the components of an ‘infernal machine,’ a bomb of some sort, perhaps even a ‘time bomb.’ ”

The Halifax police arrested the two suspects, and Power “boldly and explicitly” drew some conclusions: “These men were Fenians, Fenian bombers intent on destroying the Prince, along with HMS Canada and her crew. They were terrorists unbothered by collateral damage in their desire to strike a mortal blow at the royal family.” The local press lapped it up. “The Fenian plot filled the front pages and headlines,” Gordon explains.

But was this really an open-and-shut case with an obvious motive? Was Power’s testimony —“that the men had, while alone with him, confessed to their deadly plans”— fact rather than fiction? Were Breckton and Holmes even Fenians?

The two men were tried the following spring, and a newly appointed Nova Scotia Supreme Court justice, John Sparrow David Thompson, sent them to prison for six months. In contrast to the “sensational coverage” that marked the initial arrest, the Halifax Morning Herald acknowledged the verdict with a subdued front-page article, noting the result was “probably a lighter sentence than the public at large were expecting.” How could this judge (and future prime minister) rule so lightly in a conspiracy to kill Queen Victoria’s grandson? “The final disposition of the case,” Gordon argues, “clearly indicates that the justice system categorically rejected Power’s theory that the two men were Fenian terrorists, intent on disposing of the Prince and his crewmates.” Rather than a bona fide conspiracy, there was “a fantasy concocted by the detective, into which the facts were made, or made up, to fit.” In getting his own name in the papers, Power exploited “the paranoia and fevered atmosphere around Fenians long present in Canadian memory, and recently inflamed by the bombing campaign in the British Isles.”

The prince became George V in 1910, and two years later Power was awarded the King’s Police Medal for helping break up the very plot the courts had more or less dismissed. The local press never corrected the prevailing narrative, never called out the detective for overplaying his role. Rather, Power’s reputation continued to grow to almost mythical proportions. (As late as 2010, the Halifax Chronicle-Herald ’s weekly magazine celebrated his legend in an extensive feature.)

But fame does not a good detective make, as Power’s role in the case of Peter Wheeler proves. Wheeler was Mauritian, though the press speculated he might have been “Portuguese, Spanish, Australian, ad infinitum.” He went to sea at the age of eight, serving on a ship captained by his uncle and eventually becoming first mate. Between voyages, he lived in a boarding house run by Tillie Comeau in Bear River, a few kilometres inland from the Bay of Fundy.

On January 27, 1896, Comeau asked Wheeler to visit a neighbouring farm to get some fresh milk. When he arrived, he found the badly beaten dead body of Annie Kempton, a fourteen-year-old whose mother, father, and brother were all out of town. He covered her and, Gordon writes, “immediately raised the alarm.”

A subsequent coroner’s inquest focused on Wheeler, who was “neither entirely accepted nor fully a member” of the community and who was rumoured to be having an affair with his “morally ambiguous” landlady. Wheeler acknowledged that he had “crossed paths with Annie” the day before he found her and that she had mentioned evening plans with a friend, Gracie Morraine — so no need for Comeau to check in on the teenager, who was home alone. But Morraine testified that no such plans had been made.

“Immediately,” Gordon writes, “the question of who was lying arose. Had Wheeler lied to get Annie alone? Had Annie lied simply to have the freedom of an adolescent night alone? Or, was Gracie Morraine lying for reasons unknown?” Surely, the famous Nicholas Power could help find the answers.

Power arrived in Bear River a few hours before the inquest started, though he chose not to attend. Instead, he visited the murder scene. Brimming with confidence, he told the Courier Weekly that “he had no doubt himself that Wheeler was guilty.” In fact, Gordon explains, the detective was “so confident of his assertion that he arrested Wheeler hours before the coroner’s inquiry had delivered even a cause of death.”

At the trial, Power claimed that he had found tracks in the snow that led to the Comeau boarding house and that they were certainly Wheeler’s. He also dismissed the accused’s repeated claim that blood found on his shirt had come from snared rabbits, not Annie. The defence asked the detective whether he had searched for fingerprints on a bloody handprint found in the Kempton home — fingerprint identification being in its infancy. Power simply “blustered,” Gordon writes. “Of course, he had not examined any fingermarks, the science behind them was discredited. As a scientific detective he did not rely on spurious investigative methods.”

For the local press, it didn’t matter if the man from Halifax was right or wrong. “If the erudite Detective Power, the detective who saved the Prince’s life, knew Wheeler was guilty, that was good enough for the newshounds,” Gordon writes. “They freely and frequently fed Power’s theories to the public. The issue was decided before Peter Wheeler was charged, let alone tried.” The evidence may have been flimsy and the proceedings biased, but the detective’s unwavering belief in Wheeler’s guilt sealed the young man’s fate. He was hanged on September 9, 1896, from a makeshift gallows, at the home of Benjamin Van Blarcom, the sheriff of Digby.

After an eventful four decades on the force, Nicholas Power became the chief of the Halifax Police Department in May 1906. His was an unusually short tenure, however, lasting only until November 1907. On his retirement, the Morning Herald noted his “long record of criminal ‘round‑ups,’ ” which the editors described as “so numerous” and “so full of interest” that it would take an entire “volume to justly recount them.” With this intriguing volume, Bob Gordon has done just that. And in doing so, he’s shattered the myth of Canada’s Sherlock Holmes.

Michael Taube is a columnist for the National Post, Loonie Politics, and Troy Media. Previously, he was a speech writer for Prime Minister Stephen Harper.