George McCullagh walks out of archival obscurity and into modern consciousness on the dusty back roads of 1920s Ontario, where we first see him in Mark Bourrie’s remarkable — and long overdue — biography of one of the most consequential and least remembered Canadians of the past century. We catch an evocative glimpse of him as a young travelling subscription seller for the Toronto Globe, striding purposefully across the country byways, talking up the farmers, trying to cajole them into signing on for a publication that wasn’t as good or as interesting or as financially healthy as the Montreal Star. All this — at a formative time for McCullagh and for Canada — plays out in history’s rear-view mirror, so distant that there hardly breathes a soul who remembers how robust and how important the old Montreal Star was or, really, how important even a dull and dutiful paper like the old Globe could be in the life of its readers, scattered as many of them were in farm lots along Ontario’s concession roads, set out in disciplined grids of parallel lines and rigid right angles.

Today, George McCullagh — who peddled and eventually would own and transform the Globe — is forgotten. The journos I know at the contemporary Globe and Mail, where I am a contributing columnist, have never heard of him. Largely forgotten and vanished, too, is the world he inhabited, the nation he helped shape, the fears and passions he stoked. Bourrie brings him back, puts his name into print again, and tells us a story that nobody has told before. McCullagh — whom Pierre Berton dubbed the “Boy Wonder of Canadian Journalism”— is Canada’s unremembered magnate, a once dominant figure from the time that, down there across the border, Franklin Delano Roosevelt described as the era of the forgotten man.

This is a biography that also is something of a lament — about a world that could toss aside the memory of a man like McCullagh, flawed and damaged as he was, and about a distant period that Bourrie describes with such texture and care. Big Men Fear Me takes us back to a simpler, less complicated, and less jaded Canada; to a yeasty battle of ideas and collision of parties; and, above all, to the primacy of the newspaper.

Personally, I delivered the Daily Evening Item and the Boston Evening Globe (and on many days did so while writing for the Salem Evening News, with its image of a witch on the masthead). In my time, there still was the lingering sense that the newspaper was the poor man’s university and the wise woman’s glimpse of the world beyond the kitchen window. The paper boy (and the paper girl, too) trafficked in both commerce (those mere pennies of profit for a week’s toil of deliveries) and ideas (the ones that jumped out from under eight-column headlines, as well as those that were jammed onto the cramped editorial pages of the day). Gosh, how I miss all of that — especially the newsboy colloquies at the front step, those brief front-porch exchanges on current affairs conducted through the screen door. And yes, sometimes that newsboy (George McCullagh and, I must say, me too) dreamed about covering the events that screamed across the page in sans-serif letters, set in boldface.

With a paper he hoped would dominate a city.

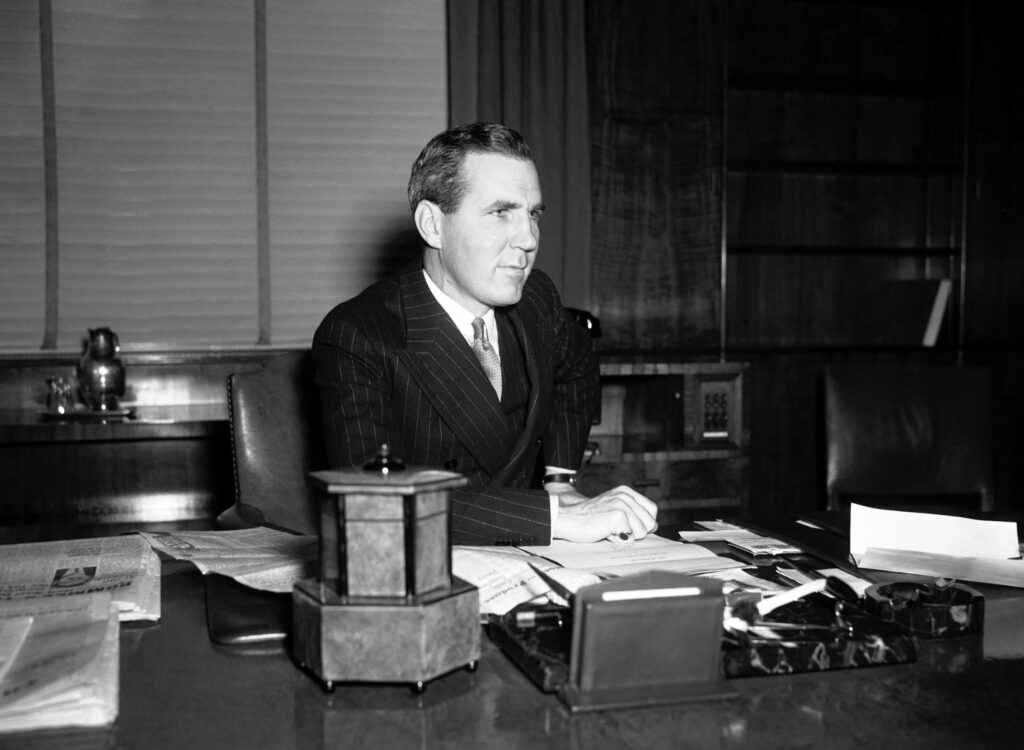

Fonds 1257, Series 1057, Item 3526; City of Toronto Archives

McCullagh eventually was hired on as a cub reporter — you don’t hear that phrase much these days, it having vanished as if it had been written in disappearing ink — and he discovered that life as a cub was granular, not a bit glamorous. But in his day, as in mine, it was freighted with possibility: that an enterprising cub might happen upon a triple homicide in his neighbourhood or a triple play in the local ball league or that the city editor might need to hire someone — anyone! — after the newsroom drunk fell down the stairs to his sad but unlamented death. How about that cubbie right over there? And so you’ll find some romance in these pages. Actually, this book holds a ton of romance — at least for us ink-stained wretches who still have glue pots on our desks, grease pencils in our top drawers, and print copies of the local paper dropped at our doors (or, just as often, thrown in our bushes).

George McCullagh may have been, as Bourrie puts it, “the most powerful and dynamic man in Canadian publishing,” but he was also an outsider, even by newspaper standards. He did, however, possess two advantages that spoke of the time and of the Toronto of his era: he wasn’t Catholic, and he wasn’t Jewish. He soon drifted into business reporting, a fortuitous development, for then as now, to paraphrase the American president Calvin Coolidge, the business of Toronto was business. Our (besmirched) hero had a gift for gab, he was good company, and he became a skilled raconteur. “McCullagh was a man who had empathy, and understood human emotions because his own caused him so much pain,” Bourrie writes.

The origin of that pain: he suffered from depression, almost certainly experienced bipolar disorder, and had, as the news euphemism of the time put it, a fondness for the grape. In short order, he was unemployed, for he also had the very bad luck of being a drunk on a paper owned by a devout follower of the prohibitionists’ creed.

But — there always was a but with George McCullagh — the man who once covered business realized he had a real gift for it. He began working as a stockbroker, and before long he was a force in financial as well as in Liberal circles, even though the overlap in the Venn diagram of the set theory of Toronto in the first half of the twentieth century was slender indeed. A seat on the University of Toronto board of governors helped to paper over his lack of a university degree or even a high school certificate. In time, he would make up for failing to acquire a diploma by acquiring the Globe, and he set out to give it respectability and reliability, two attributes that he might not have possessed in surfeit himself but that he reinforced after acquiring, in 1936, the Mail and Empire also (hence today’s masthead). He purged the old guard, and — you would have thought the world had come to an end — he sanctioned the appearance not only of horse racing results but also of advertisements for cigarettes and liquor: all this in a paper he hoped one day would dominate a Tory city known as Toronto the Good, a description that almost always was followed by the sobriquet “the town that fun forgot.”

“With cash to spend on the best executives and journalists, with job security for these people, many of whom had taken pay cuts and lived in the shadow of layoffs for the past six years,” Bourrie explains, “he would buy loyalty and productivity.” McCullagh also had bought himself a seat at Canada’s high table.

Soon the merged Globe and Mail was in its ascendancy, its reporters chasing stories across the border and around the world, its pages full of Wallis Simpson and the Dionne quintuplets, the Hindenburg disaster and the ominous stirrings of war in Europe. Before long, the entire operation took up its glittery new headquarters at the corner of King and York Streets in downtown Toronto.

Of course, not everyone celebrated the Globe and Mail or luxuriated in McCullagh’s practices, pretenses, and peculiar pet projects. William Lyon Mackenzie King, for one, worried that McCullagh had a streak of the fascist to him, and the Liberal prime minister probably was not entirely wrong. Organized labour also came to despise him for good reason. McCullagh and Joseph Atkinson, the legendary leader of the Toronto Star, conducted a decades-long range war that did not end when Holy Joe died in 1948: in a distasteful vendetta, McCullagh and his holdings continued the battle by questioning the tax status of the foundation that Atkinson created for the Star ’s continued operation. (Later, McCullagh moaned about how Ottawa treated the Star Weekly as a magazine rather than a newspaper, a status that rendered it exempt from sales taxes.) McCullagh’s critics felt he was too close to mining interests and power executives, which of course he was. And like all press lords, he surely had too many powerful friends, including, for a time, Mitch Hepburn, the Liberal premier from 1934 to 1942. Together, Hepburn and McCullagh conspired in 1937 to make Ontario a one-party province, the goal being, as Bourrie puts it, to do away with “the nuisance of parliamentary democracy.” He continues:

Other provinces, such as Quebec and Alberta, had already elected quasi-fascist regimes that used brute force and lawyers to cripple their opponents. But Ontario was the only province where political leaders actually made a deal to kill Westminster-style parliamentary democracy. McCullagh and supporters of his scheme wanted a regime that got rid of what the Globe and Mail sneeringly called “partisanship” but the rest of us would call “democratic debate.”

After several weeks, the Toronto Star exposed the plot, and Arthur Meighen, still a Conservative force though no longer prime minister, essentially killed it.

Later, McCullagh fell in with George Drew, who led Ontario from 1943 to 1948 and who reigned as head of the national Progressive Conservative Party from 1948 to 1956. The two championed the Leadership League, which pressed for tax cuts and governmental reform. But the entire undertaking was a populist flop that enhanced the reputation of no one. McCullagh’s thoroughbred Archworth did better, winning the 1939 King’s Plate as well as the Breeders’ Stakes and the Prince of Wales Stakes. Perhaps his owner took solace in the notion that horse racing was the sport of kings, one grandstand where he could best Mackenzie King.

McCullagh can be credited for fighting press censorship during the Second World War and for crusading for better procurement practices during the early years of the conflict, though Bourrie points out that much of his paper’s journalism was “jingoistic” and could be biased against Catholics and French Canadians. Even so, McCullagh can be praised for offering cottages in Port Dover, Ontario, to Globe employees who otherwise couldn’t afford a proper family holiday and for trying to resuscitate and improve the Toronto Telegram, though under his leadership its support for George Drew, in his unsuccessful battle against Louis St-Laurent’s Liberals, is a shameful example of press overreach. “The Telegram came out of the election looking ridiculous,” Bourrie writes.

By 1951, McCullagh was broken morally, politically, and medically. He was depressed and drowning in woes. A year later, at the age of forty-seven, he was dead. The reports of his death were exaggerated only in the method of his demise: It wasn’t a heart attack that killed him, as the press bellowed. It was his own hand. The next day, Brendan Bracken, a confidant of Winston Churchill and the founder of the Financial Times, wrote to Lord Beaverbrook: “I suppose it is right to use the platitude ‘it is better for him that he is dead’ about George McCullagh. The world must be a terrible place for a man with melancholia akin to madness.”

From madness to man of mystery, McCullagh is in some ways Canada’s analogue to America’s Phil Graham, the Washington Post publisher who was just forty-eight when he died. Both fought debilitating depression, both sought solace in drink, both had inappropriately close relationships with politicians they would have done better to keep at arm’s length (Graham’s dalliance was with John F. Kennedy). And both died by suicide. Graham today is dimly remembered, and McCullagh is celebrated by nobody. Bourrie toiled for years to resurrect him, but, I’m glad to say, he did not wipe away the carbuncles, boils, and blisters. His portrait of a man who once was among Canada’s most powerful figures is, to choose two apt terms, both melancholy and masterly. George McCullagh: perhaps forgotten yet, in his way, unforgettable.

David Marks Shribman teaches in the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University. He won a Pulitzer Prize for beat reporting in 1995.

Related Letters and Responses

Joe Martin Toronto

@adrianabarton via Twitter