Local newspapers are an endangered species in Canada today. At least 70 community newspapers have shut down across the country since 2008, as recorded by the Local News Research Project at Ryerson University’s School of Journalism. In 2016, the 149-year-old Guelph Mercury ended its print edition, as did the Nanaimo Daily News and the Northern Journal in the Northwest Territories. In 2013, the Lindsay Post, which had served south central Ontario for 152 years, closed its doors. And questions about what the demise of local news will mean for democracy, informed citizenry and government accountability have been roiling again in recent weeks, following speculation about the health of Postmedia (owner of some 200 newspapers, including many local and community papers) as well as the release of a parliamentary committee report on the troubled Canadian media.

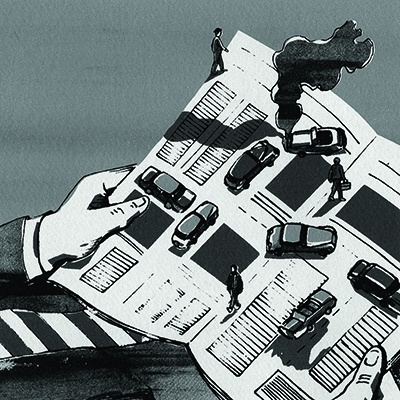

Into this fray comes an evocative portrait of a more dynamic era of journalism.

Newspaper City: Toronto’s Street Surfaces and the Liberal Press, 1860–1935, a quixotic examination of muddy York’s transition to “world class” Toronto, unveils a fascinating world of detail about how the city acquired paved streets, sidewalks and “automobility”: the ascendency of the ubiquitous car. Philip Gordon Mackintosh sees the modernization of the city through the pages of the two dominant liberal papers of the day: the Toronto Daily Star and the Globe, which, after a 1936 merger with the Mail and Empire, became the Globe and Mail.

Newspapers built the modern city not only through the creation of iconic skyscrapers—the Toronto Star building at the city’s waterfront, for instance, or the famous neo-Gothic Tribune Tower in Chicago—but also by fuelling debate about the issues of the day and influencing the decision makers. The newspaper reflected the daily life of the city and readers’ concerns informed the newspaper. Zeroing in on the years between 1860 and 1935, Mackintosh sees the city in the newspaper and the paper as the city. “The historical newspaper is urban geography made textually manifest … it developed a capacity for representing and reproducing the city in broadsheet.”

Jean-Luc Bonifay

There is no better illustration of the symbiotic relationship between the newspaper and the city than the story of how Toronto streets changed from dirt to pavement. At the turn of the last century Toronto had six daily newspapers, some publishing several editions a day, hawked on street corners by squadrons of “newsies.” Newsies—often barefoot, ragged children who, by law, had to be at least eight years old, and whose earnings contributed to the family income—were estimated to number 600 in the late 1910s.

Late Victorian Toronto was a dirty, dusty, smelly place with people and animals living in close quarters. It was normal for families to keep chickens, cows and pigs in the backyard. Feral dogs and cats roamed the streets. Aside from dogs “worrying” pedestrians, there was the problem of dead dogs whose stinking corpses were left rotting in the street. In graphic detail the city news section of the Globe campaigned for reform, and reported on “the fetor emanating from the large, putrefying mastiff at the corner of King and Yonge; the five dead dogs mired in the cesspool at the corner of Queen and Jarvis streets; or, worse, the dead pig decomposing next to the sidewalk on the west side of Church Street between Queen and Richmond.”

Some practical-minded construction workers took a pragmatic approach to the disposal of dead carcasses. The Globe’s City News section of August 11, 1873, reported that “while constructing an extension of Berkeley Street in 1873, the road builders filled a hollow in the road with a ‘dead horse, butcher’s offal, cleanings of lanes, dung, and material of several other descriptions,’” no doubt to very unpleasant olfactory effect for the citizens of Berkeley Street.

To this gallimaufry of animal detritus, add backed-up water closets and cesspools leaking from Toronto’s houses and rear cottages; mounds of uncollected garbage strewn by wandering animals and rag pickers; the rotting and leaking carcasses of all the various fauna in the age of farm animals in the city; and even the tobacco juice of countless men and boys expectorating the salivary by‑product of chewing tobacco.

We are reminded that many of the residents of Toronto were immigrants from the rural areas of Europe, farm people who had fled poverty or persecution. The newcomers created a rural farm life in the city. They were accustomed to the smell of the farmyard and it is not surprising that they created what Mackintosh calls a farm-like city.

But the liberal press of the day, voicing the concerns of the up-and-coming bourgeoisie, campaigned for an end to the filth using the full range of journalistic devices, from sensational news reports to flaming editorials such as one by Edmund Sheppard of the Evening Star that described the cattle drives down Bathurst street as a “cauldron of steaming animalism.” The papers held reader-participation competitions such as the “Swat the Fly” contest launched by the Star in July 1912 out of concern that flies were, according to the early city planning department, “the most dangerous wild animals of North America.” In a move reminiscent of Mao’s campaign in the 1950s to rid China of all flies as one of the “four pests,” the Star offered children under the age of 18 prizes up to $50 for the most flies swatted or trapped, “to make Toronto as far as possible a flyless city.” The winner, young Beatrice White, is pictured standing in what looks like a vacant lot surrounded by metre-tall, rectangular, screened flytraps apparently full and buzzing with flies.

The question of paving these squalid dirt paths was a controversial new idea brought forward by some of the leading citizenry. In 1880 the politics surrounding the paving of Toronto streets were newsworthy enough for the Globe to have its own “special pavement reporter.” Paving technology was in its nascence, and for a time the paper championed the cedar-block method of street covering—15-centimetre cedar logs stood upright tight against each other to form a kind of mosaic. Grouted with gravel and coal tar and standing on planks or cement, they were cheap, plentiful and slow to rot. But, as time went by, with engineering innovation and the invention of new materials, controversy erupted in the pages of the newspapers over pavements, especially asphalt.

Asphalt was expensive and there were doubts about its effectiveness—early asphalt with too much oil in the composition could catch fire. The Globe is described in the book as “fawn[ing] over asphalt,” declaring that “‘poor buildings, irregular streets, almost anything that is hideous in architecture becomes passably decent’ with asphalt paving in front of it.” But the Evening Star’s headline in 1894 disagreed with that assessment: “Asphalt Fails the Test.”

The choice of which pavement to use did not rest solely with the city councils of the day. The paving of Toronto’s muddy streets was financed by a system—the petition system—that fuelled neighbourhood feuds and initially led to a patchwork quilt of stone, macadam, cedar blocks and asphalt street coverings all over the city. Following an assessment, property owners had to pay part of the cost of improvements to their streets on the grounds that it would improve the value of their property. Moreover, an owner had a say, even a veto, in the kind of pavement to be used. Many owners petitioned for the cheapest pavement, against the advice of the long-suffering city engineer. This was understandable considering that asphalt cost up to $2.80 per square metre and cedar blocks, which would last for five to seven years, about 50 cents a square metre. Some residents, on once-posh Jarvis Street, decided that they did not want the additional traffic that would likely ensue if they upgraded their street.

A photo taken at the corner of Queen Street West and Manning Avenue, reprinted in the book, shows cedar blocks on Manning running into the asphalt of Queen Street as well as the bricks on Queen where the streetcar tracks ran. The curb and sidewalks on Manning were made of wood planks while on Queen Street they were concrete.

Aside from the resulting hodgepodge appearance, there was another problem. Paving companies would bribe property owners to petition for their product, further complicating the system and creating a kind of moral hazard. The newspapers campaigned against the petition system while simultaneously relying on advertising from paving companies—an example of what Mackintosh calls “liberal contradiction” (more on that below).

The introduction of the car, “automobility,” that followed the paving of streets created another type of news story for the papers to report on. In the days before helicopter parenting it was normal for children to be sent outside to play, unsupervised, on the streets. With the arrival of cars, a shocking number of children were hit, injured and killed. The three years between 1931 and 1934 saw 30 deaths a year of children four and under.

The papers’ coverage of these events reflected the attitude of the time toward children. Children, who seem to be regarded as little adults, were held responsible for the accidents in a bizarre way. Rather than focusing on rules of the road for cars, Globe editorials exhorted parents to instruct their children on road safety, apparently expecting “the little nippers” to save themselves.

The car took a toll on adult pedestrians as well, with the papers reporting on the challenge of dodging cars while crossing the street or exiting a streetcar. The death of a prominent citizen, C.A.B. Brown, killed by a hit-and-run driver as he stepped down from a streetcar in 1920, was big news; the Globe warned that “unless there is a speedy end to the killing of men, women and children in the city, the feeling aroused will work injury to motorists as a class, without discrimination.”

The “contradictory liberalism” of which Mackintosh accuses newspapers is a theme in his book; he frames Toronto’s modernization in this period as an expression of this idea. Liberalism, he says, has three pillars—liberty, equality and property—and when the third pillar, property, dominates, as it does in city building as seen through the pages of the liberal press, then the exigencies of property ownership and capitalism end up in contradiction with equality and liberty. The press is instrumental. It is in the pages of newspapers that the city’s liberal bourgeoisie champion both the public interest and their own private interests, which are often contradictory. When cars were first introduced, the pages of the paper decried the shocking number of “little tots” killed by cars; at the same time the papers depended on automobile ads and their feature pages advocated for the car as “the king of vehicles … that has won its place in the civilized world … the chariot of prosperity.”

Newspaper City is not an easy read. It is an academic book with references and source material included in brackets within sentences, certainly an impediment to narrative flow. The author seldom opts for a simple, clear word when an obscure word can be found. Words such as “imbricating,” “bourgeois mimeticism” and “prolix” sent this reader scrambling for a dictionary. Still, Mackintosh brings to life a time when newspapers were essential building blocks in the development of cities. Newspapers provided a common information base for citizens to form opinions about how their city should develop; they were a critical element of democracy even though, as the author suggests, the actual decision makers were an elite group of city burghers closely linked to the newspaper owners.

According to the 2016 census Canada is increasingly an urban country, with 82 percent of our population living in cities. But urbanization has not saved the daily newspaper and the era of the “newspaper city” is coming to an end.

In time, online news publications and social media will likely fill the gap left by the demise of these newspapers. But the transition is taking a long time. Meanwhile the absence of skilled reporters covering local news, attending city hall and school board meetings, researching, reporting and holding the powers that be to account will be felt; potentially at considerable cost to democracy.

Beth Haddon, a former broadcast executive with CBC and TVOntario, is a contributing editor to the magazine.