In August 1840, Ellis Gray Loring, an anti-slavery lawyer in Boston, sent a letter to his friend Reverend Hiram Wilson, of Toronto. He mentioned a lecturer named Fred, an ex-slave who had escaped “two years ago” from his owner, Thomas Auld. Loring suggested this lecturer’s powerful oratorial abilities could “produce great effect,” and that Wilson should consider buying his freedom.

“Fred,” as it turned out, was the leading abolitionist Frederick Douglass. While nothing ever came of Loring’s proposal, just think how close we came to having the great statesman and social reformer writing his best-selling autobiography, Narrative of a Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave, in Canada.

Douglass, like others who face personal hardship and turmoil, understood that freedom was a cherished value in a democratic society. Their stories remind us that the ability to speak, think, practise, protest, achieve, and accomplish one’s goals — without fear of restriction, retribution, or limitation — is something we should never take for granted.

What about those who aren’t free? For such individuals and groups, the thirst to acquire personal, political, and economic freedom is unquenchable. Whether they’re escaping repressive societies in Saudi Arabia or Venezuela or joining a migrant caravan in Central America, hoping to reach the Mexico-U.S. border, they do everything in their power to live open, unrestricted, and fulfilling lives. Three recent books take up the long, winding road to freedom that’s familiar to so many today by looking back on the nineteenth century.

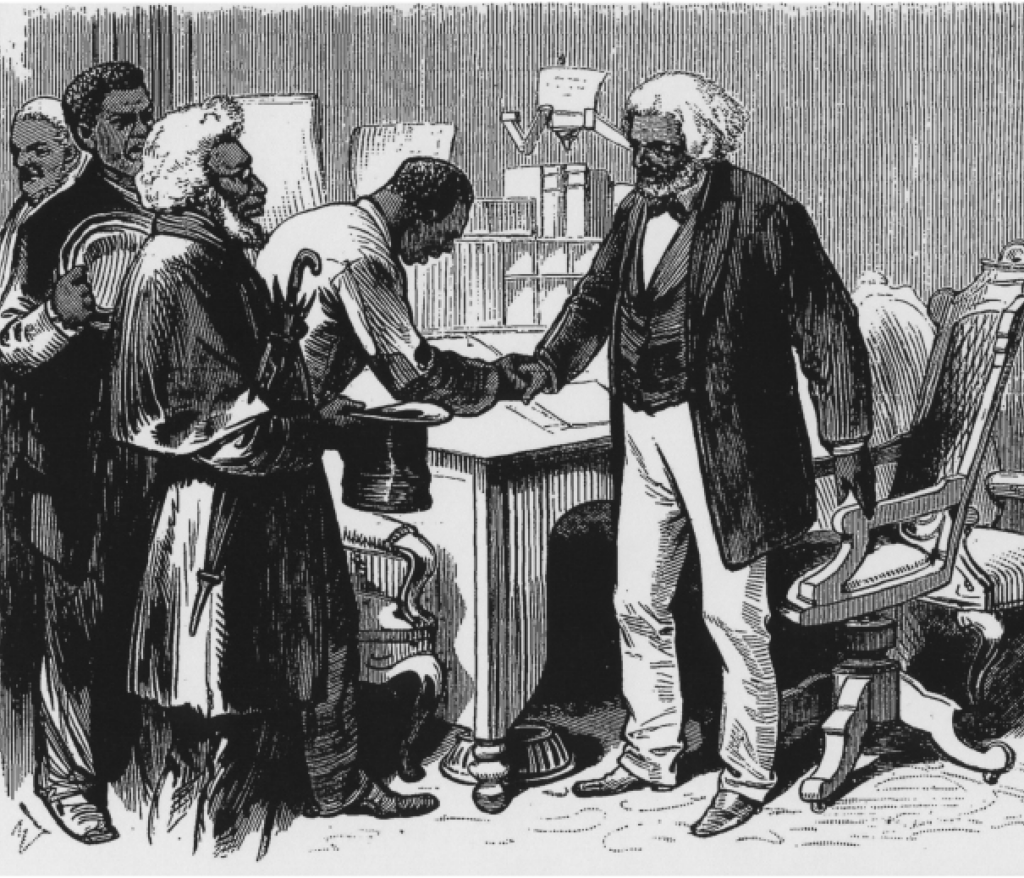

In 1877, the former slave Frederick Douglass became U.S. marshal for the District of Columbia.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (April 7, 1877)

David W. Blight’s Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom is a fine examination of a remarkable man who escaped the painful shackles of his early life to become a leading advocate of freedom. With the publication of Narrative, in 1845, Douglass became one of America’s most influential writers and orators. Before and after the Civil War, he fought for equality and changed the hearts and minds of many around the world.

Douglass grew up a slave of mixed-race background. As a child, he secretly learned how to read and write, with the help of Sophia Auld, his owner’s wife. As he described it in Narrative, the discovery of knowledge and education was revelatory and made him aware of “the pathway from slavery to freedom.”

In 1838, Douglass escaped from slavery and tasted freedom for the first time. He married his first wife, Anna Murray, a free black woman from Baltimore, and began to take account of the “sharp distinctions between a Southern slave society and a Northern free-labor society.” Settling in the whaling community of New Bedford, Massachusetts, he encountered racism but found opportunities to earn money at odd jobs, such as shovelling coal and cleaning chimneys for wealthy white families. He joined the small African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and became a faith leader. Blight’s sweeping biography, which won the 2019 Pulitzer Prize for history, details how Douglass’s sermons to “fugitive slaves and free blacks” brought him acclaim for his diction and presence and helped him establish contacts with white abolitionists like Loring “earlier than scholars have previously known.”

Douglass was a Republican by political persuasion, although he would certainly have been on the radical side of the party faithful. What would become the Grand Old Party was relatively new, having been established only in 1854. His reactions often “ranged from vehement opposition to cautious support,” although he did “his best to uphold the Radical Abolition platform within the ranks of the Republicans.” This allegiance has been touted by modern Republican adherents like Donald Trump (although remarks the president made in 2017 indicate a serious misunderstanding of Douglass’s most basic biography).

The former slave was awestruck by Abraham Lincoln during their first meeting in August 1863. He firmly believed he had found in the president “the ultimate counterpart actor — at least in the power the other character represented.” There were issues on which they passionately disagreed, including how quickly to eliminate slavery and Lincoln’s short-lived flirtation with the American Colonization Society, the controversial group that advocated sending free African Americans back to Africa (a movement that ultimately led to the creation of Liberia). Nevertheless, Douglass “heard echoes of his own jeremiads and his relentless war propaganda” during the president’s second inaugural address, in March 1865. He was thrilled when Lincoln called him “friend” and treasured Lincoln’s words of praise: “There is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours.”

Blight’s analysis is largely devoted to Douglass’s travels, meetings, and speeches throughout the United States. He spends less time exploring the vivid connections to Canada, aside from the Loring-Wilson letter, but such connections will certainly intrigue Canadian readers.

Douglass, of course, was well aware of the Underground Railroad and of the thousands of black slaves who sought freedom in the Maritimes and southern Ontario. He made sure copies of his anti-slavery weekly newspaper, the North Star, which ran from 1847 to 1851, circulated north of the border. And Canadian delegates attended an 1855 conference of the Radical Abolition Party, to which Douglass acknowledged being a “devotee.” They would go on to pass “a resolution affirming the use of violence to overthrow slavery.”

In 1859, following the radical abolitionist John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, an attempt to arm a slave revolt in Virginia, Douglass fled to Canada and stayed briefly. Although he disagreed with Brown’s tactics, he feared being labelled a co-conspirator nonetheless. Blight notes that he stayed at a tavern in Clifton (now Niagara Falls) and “hated his current exile and worried about the possible confiscation of his property if his indictment held.” He continued to publish columns, such as “Capt. John Brown Not Insane,” which Blight describes as “not only a vintage, sharp-edged piece of abolitionism, but also Douglass’s earliest effort to help build the majestic cross of John Brown’s martyrdom.” He would also travel to Toronto, sail down the St. Lawrence River on the Nova Scotia, en route to Liverpool, and write in amusement about, among other things, “the Frenchness of Montreal.”

Strangely, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom does not mention Douglass’s appearance at Toronto’s St. Lawrence Hall, in 1851. A featured speaker at the North American Convention of Colored Freemen, he discussed the resettlement of U.S. slaves with Henry Bibb, a black abolitionist and the convention’s organizer. (Another notable attendee, Mary Ann Shadd, would become North America’s first black female publisher when she started the Provincial Freeman, just down King Street from St. Lawrence Hall, in 1853.) It’s surprising that Blight, who directs the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale University, fails to refer to this important gathering.

The omission doesn’t take away from an impressive tome, however. In astonishing detail, we see the various stages of freedom that Douglass experienced throughout his seventy-seven years: personal, educational, political, and spiritual. In 1872, without his knowledge, Douglass became the first African American nominated for vice president. In 1884, following the death of Anna Murray, Douglass would marry again — to Helen Pitts, a white abolitionist twenty years his junior. And five years after that, he would travel to Haiti, where he served as the U.S. ambassador until 1891. Throughout it all, he continued to write, teach, and inspire people.

Edna M. Troiano’s Uncle Tom’s Journey from Maryland to Canada is a short albeit intriguing examination of another heroic individual, Josiah Henson. Born in 1789, in Maryland, Henson was the abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe’s primary inspiration for Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the novel Lincoln supposedly credited with starting “this great war.” (This was long before the phrase “Uncle Tom” became something of a derogatory term for a black man considered overly subservient.) After escaping a life of slavery, Henson became a minister, abolitionist, and author in Canada, and he was active in helping others escape through the Underground Railroad.

His father was enslaved to one man, Francis Newman; Josiah, his mother, and his siblings belonged to another, Josiah McPherson. The latter was a relatively friendly, kind, and liberal slave owner; McPherson was “obviously fond” of the boy, Troiano writes, since he “named him Josiah after himself and added the name Henson for one of his uncles who was an officer in the Revolutionary War.” McPherson’s life ended tragically due to an accidental drowning, and Henson would write in his autobiography that life before the accident was “a bright spot in [his] childhood.”

Henson remained a slave for more than forty years. With his intelligence and ability, he established a good relationship with Isaac Riley, another slave owner. When Riley’s debts became too great, he sent Henson, his wife, Charlotte, their two sons, and eighteen other slaves to a plantation in Kentucky, owned by his brother Amos. As Troiano explains, this involved Henson leading the large group “on a journey of one thousand miles through unfamiliar territory and over mountains on foot in the dead of winter.”

Even though Henson served the Riley brothers faithfully for years, they still cheated him when it came to buying his freedom. Troiano’s research reveals a set of original manumission papers — documenting the promise of freedom — that priced Henson’s release from slavery at one dollar. He actually arranged to make a payment of $450 to pay off all the debts related to him and his family. Behind his back, however, Isaac Riley “had added three zeroes” — creating an impossible amount for Henson to raise.

Henson had had enough. He knew friendly abolitionists in Ohio, who “convinced him that Canada was the only place where he could be confident of remaining free.” He gathered the family together, and they made their way to Cincinnati, where he “felt relatively secure.” American Indians helped them part of the way, providing food and shelter. A poor ship’s captain named Burnham then took them to Buffalo, gave Henson a dollar, and asked a ferryman to complete their journey to Canada. His only request was that Henson “be a good fellow,” Troiano writes, to which Henson replied, “I’ll use my freedom well; I’ll give my soul to God.”

It was a promise he kept.

The family established the Dawn Settlement for fugitive slaves, near modern-day Dresden, Ontario, and made a good life for themselves. Henson became a beloved preacher, renowned for inspirational sermons. He began to learn how to read and write from his son Tom, but he never “became adept at either,” Troiano writes. Instead, the preacher had to “depend on others to write his letters, documents, and autobiographies.” He would build a sawmill and a gristmill, aided by thousands of dollars raised by wealthy American philanthropists. He even became friends with Hiram Wilson — the same man who could have helped to free Douglass — and together they built the British-American Institute and other schools. Henson also spoke to American and British audiences about slavery and came into contact with prominent individuals like the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He died in Dresden, in 1883, at the age of ninety-three.

Christopher Klein’s When the Irish Invaded Canada: The Incredible True Story of the Civil War Veterans Who Fought for Ireland’s Freedom examines another astonishing episode in the quest for deliverance: the Fenian raids. These battles occurred between 1866 and 1871, when Irish-born veterans who had fought on both sides of the American Civil War joined forces in hopes of securing freedom for Ireland. And it all happened on Canadian soil.

The word “Fenian” refers to two fraternal organizations, created in 1858, that championed an independent republic. On one side was the Irish Republican Brotherhood, founded in Ireland by James Stephens; on the other side was the Fenian Brotherhood, founded in the United States by John O’Mahony. The former attempted to branch out in the U.S., but the latter was too strong and overwhelmed it. Stephens opposed raids on Canada — still a British outpost — while the more dominating O’Mahony salivated for opportunities to strike.

During the four-year Civil War, some 20,000 Irish Americans fought for the Confederacy, and up to 200,000 fought for the Union. “To many Fenians and Irish republicans,” writes Klein, “enlistment offered the opportunity to gain valuable training for the eventual revolution they planned to launch in Ireland.” The price of such training was high: they “didn’t expect to have to die in such numbers.” In fact, Irish soldiers suffered disproportionate losses, because so many were “placed on the front lines to serve often as little more than cannon fodder.”

In April 1866, one year after the Civil War’s conclusion, in May 1865, the first Fenian raid occurred at Campobello Island, New Brunswick. U.S. president Andrew Johnson supported the move, even though he didn’t necessarily trust the Irish republicans. Bernard Doran Killian, treasurer of the Fenian Brotherhood, led 500 to 600 men toward the island in what they hoped would be the first step toward independence. The New York World romanticized the subsequent battle, suggesting “the Fenians would establish a provisional government on the island, elect O’Mahony president, and use it as a base to launch an army of twenty-five thousand men to conquer New Brunswick and rechristen it the ‘Republic of Emmetta’ in honor of the Irish patriot Robert Emmet.” They didn’t come close to accomplishing their lofty goal, however, as the British sent in warships and pushed them back.

The Irish republicans did have one significant success two months later, during the Battle of Ridgeway, near Fort Erie. Under the leadership of John Charles O’Neill, they were able to defeat the inexperienced Canadians, who lost seven members of the Queen’s Own Rifles. It was a historic victory, Klein notes, and the first time since 1845 that “an Irish army had emerged victorious against forces of the British Empire.” Newspapers in Toronto, Boston, Detroit, and Dublin took note. Some even started to believe that a slew of Fenian Brotherhood victories on the battlefield of a British colony could help give the long-suffering Irish a measure of the freedom they had long desired.

It was not to be. The Fenians lost most of their raids at locations like Pigeon Hill, Eccles Hill, and Trout River. Several newspapers described their attempted invasions of Canada with the ignominious phrasing “the Fenian fiasco.” Moreover, O’Neill’s once-glowing reputation was sullied when he tried to join forces with the Métis leader Louis Riel. Not only did this alliance never take place — Riel was wary of the Fenians — but O’Neill couldn’t even figure out where to attack the British in Manitoba. As Klein explains, “Not only had he failed to invade Canada” during this 1871 battle, but due to his poor sense of geography, “he had failed to enter Canada — at least in the eyes of the U.S. government.” This bizarre piece of history has led some to suggest his short-lived victory at Ridgeway was nothing more than a “fluke in the general’s record.”

Ironically, the country that truly gained a measure of freedom and confidence was not Ireland but Canada. Klein suggests we “might not have been a nation at all without the Fenians.” Why? “The subsequent Fenian raids into Ontario and Quebec and the enduring threat of another attack alarmed many residents along the American border,” he writes. That helped delegates to the Charlottetown Conference, like Thomas D’Arcy McGee, convince people in the Province of Canada that “a union was necessary in order to protect their families and property.” Confederation would happen just over a year after the first raid.

Michael Taube is a columnist for the National Post, Loonie Politics, and Troy Media. Previously, he was a speech writer for Prime Minister Stephen Harper.