Unprecedented bushfires and heat waves in Australia. Increasingly intense hurricanes and cyclones. Melting glaciers and permafrost. Warming and acidifying oceans. Locust swarms devouring east Africa. And in the face of it all, global greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise. Even if the aspirational Paris Agreement were fully implemented today, we’d still be headed toward a 3.2-degree Celsius rise in global temperature, with far worse, indeed catastrophic consequences.

According to the Emissions Gap Report 2019, released by the United Nations Environment Programme this past November, we need far deeper cuts in emissions to stop the unfolding apocalypse — a more than 7 percent reduction every year for the next decade. The measures we’ve taken so far have been like trying to stop a flood with a toothpick. Revenue-neutral carbon pricing, renewable energy initiatives, tree planting and other remediation projects, millions of soothing words from “concerned” politicians, along with angry, passionate, and despairing ones from young environmental activists like the eight-year-old Indian prodigy Licypriya Kangujam, Sweden’s Greta Thunberg, and our own Autumn Peltier — none of it stands a chance of holding back the waters.

Our failures reflect what Mark Carney, the UN’s new special envoy on climate change and finance, has called the “tragedy of the horizon.” The effects of today’s emissions will continue far into the future, well beyond current business and election cycles, not to mention the lives of many of us, including the worst of emitters. But too many of us can’t — or won’t — look past the present moment to see the climate chaos that awaits us if we stay on our current path.

Yet some of those who are watching as our planet heats up dare to dream. Some of their dreams are plain crazy and desperate, threatening more harm than good (think of using aerosols to dim the sunlight, or filling the seas with iron filings to promote carbon-fixing algal blooms). But other dreamers want to change the chugging, carbon-spewing behemoth of industrial production itself, rather than imagine science fiction schemes to mitigate its ill effects.

Are we playing chicken with the inevitable?

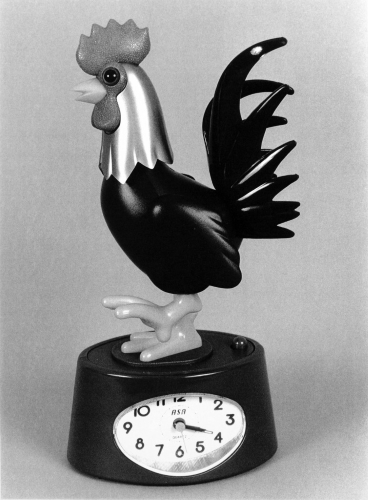

Christian Boltanski, Untitled from Favorite Objects, 1998; SOCAN, copyright 2020

Tom Rand, a venture capitalist and senior adviser at MaRS Discovery District, in Toronto, and Paul Huebener, an eco-humanist and Athabasca University English professor, both believe a green future is possible. And yet . . . “Nothing I see on the cleantech horizon — no matter how low its perceived technology risk, promising its economics, or clever its management team — is scaling anywhere near fast enough to slow climate disruption,” Rand admits in The Case for Climate Capitalism. “I may be optimistic on cleantech as an investor, but I’m deeply pessimistic on climate as a human.” Huebener, too, author of Nature’s Broken Clocks, knows we’re in for a bumpy ride: “The experience of trial and error must be understood as the new reality, as a defining and perpetual condition of life within an era of ongoing climate disruption.”

Both know that we face a mountain of greed, negligence, stupidity, and myopia. If, as Rand says, only “loons or charlatans” deny anthropogenic global warming outright, too many more are unwilling to do anything serious about it. Australia is literally in flames, but the government approved a massive new coal mine just last summer. In the United States, the president has rolled back dozens of environmental regulations and has rejected the Paris Agreement. Here at home, the premier of Ontario has spent $230 million to cancel renewable energy projects and has even closed down several electric vehicle charging stations. Meanwhile, in Ottawa, the Liberal government — presenting itself as a group of progressive climate change heroes committed to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 — bought the Trans Mountain Pipeline in 2018. And the Alberta Court of Appeal recently ruled against federal carbon pricing. (Canada, we should be reminded, has the third-highest per capita GHG emissions among all OECD countries, trailing only the U.S. and Australia.)

Doing anything meaningful about climate change will be an uphill climb, which Rand approaches with the determined belief that capitalism, having led to the crisis in the first place, can also get us out of this mess. He positions himself as an economic moderate: he rejects both neo-liberal laissez-faire approaches, which he mislabels “neoconservative,” and the “far-left” views of Naomi Klein, which, it must be said, he largely misrepresents.

Rand suggests that Klein proposes an “all-or-nothing view on climate.” But that’s just not the case, as she makes clear in This Changes Everything, from 2014. Rand also claims that she “demands nothing less than a centrally controlled, top-down economic system that prescribes solutions rather than have the market discover them.” In fact, she explicitly rejects such systems. Ironically enough, Rand’s views converge with Klein’s more than he cares to admit. Both favour a mixed strategy to combat climate change. Both favour decentralized power generation (although Klein supports community control of utilities). Both want the state to intervene forcefully to cut back and eventually eliminate carbon emissions. Indeed, both favour strong, on-the-ground protests to drive the point home.

Rand differs from Klein in placing his faith primarily in market strategies and mechanisms, including incentives, which he explains in a readable way. In a nutshell, he wants to make clean tech profitable and to develop, through investment, new forms of power generation and storage that would compete effectively with carbon-intensive sources. He favours carbon pricing and a flexible regulatory scheme, in which the state establishes emissions limits and private industry figures out the rest.

Pension funds, Rand suggests, would be a sensible choice to make substantial capital investments, given their relatively long-term interests in a stable future. He proposes a type of state-funded green bank, which could provide seed capital for clean enterprises to fill “market gaps.” Green bonds, funded by the public but run privately, could also help. As for the World Trade Organization, which has shut down green enterprises because of “antiquated” rules that “trump current climate needs,” he simply proposes rewriting agreements and making the WTO a global enforcer of emissions standards.

Achieving reform of the WTO in any hurry seems a stretch, as does Rand’s notion that “capitalism must be radically reformulated” (although, in fairness, some powerful voices at the World Economic Forum in Davos recently made the same point). There are other practical barriers to the transition he envisions, including that problem of scaling up solutions. At one point, he describes Climeworks, a European enterprise that has built 100 efficient carbon-capture machines, which are indeed worthy of praise. But to take even 1 percent of the carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, we’d need 5 million of them — operating for a decade.

Within any movement, there are those who offer few practical solutions for change but accurately capture the contemporary mood. Paul Huebener is one such person. He believes that to better grasp where things went wrong, environmentally, we must better understand our relationship with time. The nub of Huebener’s argument may be found in a short, incisive philosophical paper that Michelle Bastian, of the University of Edinburgh, published in 2012. In “Fatally Confused: Telling the Time in the Midst of Ecological Crises,” she defines a clock as “a device that signals change in order for its users to maintain an awareness of, and thus be able to coordinate themselves with, what is significant to them.” The classic timepiece measures seconds, minutes, and hours, but it does not track all that is significant — there’s no dial for melting ice caps, mass extinction, the ongoing depletion of natural resources. As Bastian put it, “We are increasingly out of synch.”

Bastian proposed “condensed clocks,” an idea epitomized by the leatherback turtle. “An animal that most often symbolizes slowness and steadiness,” she wrote, is among the best placed to spur thinking “about speed — the speed of climate change.” The “turtle clock” signals major changes in coastal habitats, as well as current fishing practices that threaten its survival; it highlights our own lack of a coordinated, timely response to environmental change. And as anyone knows who has bothered to check the time on that clock, we’re running late.

Huebener gallops off in all directions with Bastian’s condensed clock idea. His book brings together dying coral reefs, grizzly–polar bear hybrids, the Slow Food movement, indoor ski resorts, poetry-inscribed bacteria, and countless other examples of a world that is temporally out of whack. He asks us to enlarge our imaginative reach, to reconsider time as a mutually enmeshed collection of temporalities — natural and artificial, clashing and dynamic — rather than a single, inexorably forward-moving process.

“If we are to understand and respond adequately to the visions of time that enable unsustainable practices,” we must first develop a “critical temporal literacy.” That, in turn, will reveal damaging practices as socially constructed and perilously decoupled from the natural world — often manifested as expressions of power over excluded and marginalized people.

Clock time, in the classical sense, is money. And time is power. When it comes to pushing through pipeline projects, speed is of the essence; when it comes to drafting environmental regulations, power somehow imposes a slow and stately pace. All of us are at the mercy of artificial schedules, deadlines, and hours dictated by others: “We go about our daily work as though electric lights and always-connected smartphones make the setting of the sun irrelevant, yet our bodies crave nightly darkness and sleep.” Of course, sleep is the enemy of ceaseless capitalist production, and perhaps it’s no surprise that military research is even now being conducted on how to do without it.

Whether we sleep or burn the midnight oil, GHGs pour into the air, while the geological layer of the Anthropocene thickens and solidifies with nuclear waste, chemical pollutants, and copious chicken bones. Then there are the million plastic bottles we produce every minute: by 2050, the oceans may well hold more plastic garbage, by weight, than they do fish. Tick‑tock.

Huebener describes the clock motif as “an experiment in metaphor,” one that he presses well past its breaking point. He wants us to find clocks in “every object, every action, every process.” Time is always political, he argues. “And every discussion, in a sense, is a discussion of time. Every narrative, every object, every living thing is a clock, each one crucial and incomplete, beautiful and broken in its own way.”

But, in many ways, “broken” is the wrong word. While nature’s clocks are certainly incomplete measures, they are measuring time in alarming ways: Banana plants are bearing fruit in Vancouver. Trees are budding in September. Animals are becoming nocturnal in order to avoid humans. Climate change has created mismatches that have separated some animals from their food sources and have introduced new prey to new predators. Things are wildly out of sync, certainly, but the clocks are still telling time.

Huebener is most lucid when analyzing a commercial for Go RVing Canada. Heavily suffused with temporal ideology, the minute-long clip shows a family rushing around frantically, beset by cares and pressures on all sides, preparing for a vacation getaway. Their gas guzzler transports them to a timeless, natural setting (albeit heavily manicured), where they become a family at peace. The false bifurcation of nature and society couldn’t be clearer. Ignoring the entangled, sticky web of dynamic, contending temporalities that affect both the human and the non-human, the commercial presents two neatly bounded realms — one an escape from the other. You just need a costly, carbon-spewing vehicle.

Such imaginary space-time travel is precisely the kind of blithe cultural assumption that is causing the trouble. There is no unchanging natural realm where time either ceases to exist or proceeds slowly and smoothly. In fact, as the environmentalist Bill McKibben has pointed out, we are the slow ones, unable to keep pace with the rapid and perhaps catastrophically changing natural world. There is no getting away from this world, and if we’re going to fight climate catastrophe, we had better realize that.

We need to reframe time-based assumptions, both cultural and natural, Huebener argues, including “the ways in which they are limited and inadequate, or the ways in which they erase forms of time that have important implications for social power and sustainability.” If we can successfully do that, we will have “better insight into the ways in which problematic assumptions about time have infiltrated our own minds.”

The issue here is awareness — an essential starting point for a much-needed cultural shift. But what do we actually do with this awareness? “Our best hope,” says Huebener, “is that seeing the early stages of collapse with our own eyes will inspire us to prevent the later stages.” In this way, he’s more optimistic than Rand, who would probably never write, “If the Anthropocene is made of cement, then thoughtful narratives are the weeds that crack the sidewalk.”

Literature is a way of reimagining time, of acquiring temporal literacy. Huebener complements his book with numerous passages, including from “Quartz Crystal,” by the poet Don McKay: “It becomes clear that I must destroy my watch, that false professor of time, and free its tiny slave.” At a remove, readers might dismiss these literary lessons as hopelessly impractical. But that would be to miss the point. Huebener is not so much creating change as representing it.

Increasing numbers of people around the world are waking up to a climate emergency, and in countless ways they are coping, imagining, and resisting. Huebener and Rand join hands with those — like the 50 million people in India who produced an 18,034-kilometre human chain this past January — who are demanding action. Both writers are dreamers. Both face the same enormous obstacles that the rest of us do. Both are deeply imagining how we might all overcome the most urgent of challenges.

Some may dismiss the bookish Huebener and his desire to raise temporal consciousness through literature as quixotic, but it’s Rand, the savvy hands-on capitalist, who proclaims, “We need a new theology.” In their disparate ways, both have made themselves part of the solution. The ripple effect of their books, combined with the ripple effects of countless others, might just save our species from extinction.

But, no matter what clock we consult, we’re running out of time.

John Baglow reads and writes in Ottawa.

Related Letters and Responses

Tim Draimin Toronto