On the southern edge of Sarnia, Ontario, lies a cluster of more than sixty oil refineries and petrochemical plants, an industrial wasteland known as Chemical Valley. In the 164 years since Lambton County became the site of North America’s first commercial oil well, this small city at the mouth of the St. Clair River has turned into one of the most polluted places in Canada. Toxic chemicals pour from smokestacks, carcinogens ride the breeze, black muck leaks up from the soil, and residents stand a shockingly high chance of dying of leukemia. It is not a particularly cheerful setting for a series of short stories, but then David Huebert has never been a particularly cheerful writer. Thank God for that. First in his 2017 collection Peninsula Sinking and now in Chemical Valley, Huebert’s uncanny facility for spinning densely poetic fiction out of the tawdry horror of twenty-first-century life has made him one of the most captivating authors of the past decade.

Sarnia is a microcosm of the modern world. As a character in “Oilgarchs” puts it, “everyone lives in Chemical Valley” these days. But Huebert knows this is only partially true: because fumes are blown south over the Indigenous communities of Aamjiwnaang and Walpole Island, those in the city share the false hope that they will be spared the most brutal consequences of their industrial activities. The feeling that the climate apocalypse is definitely here (but not yet for all) is the psychological engine that drives these narratives. The characters live in a dying world, but some of them are also making a decent living helping to kill it.

The book is divided into two sections, the five “Chemical Valley” stories, set in and around Sarnia, and the six “Dream Haven” tales that take place in other parts of Canada and the United States. Occasionally a character from one piece will show up in another, but what really gives the project a sense of cohesion is Huebert’s artistic sensibility. There’s a morbid tenderness at play here, an awareness that even a poisoned landscape can contain beauty, mystery, and wonder.

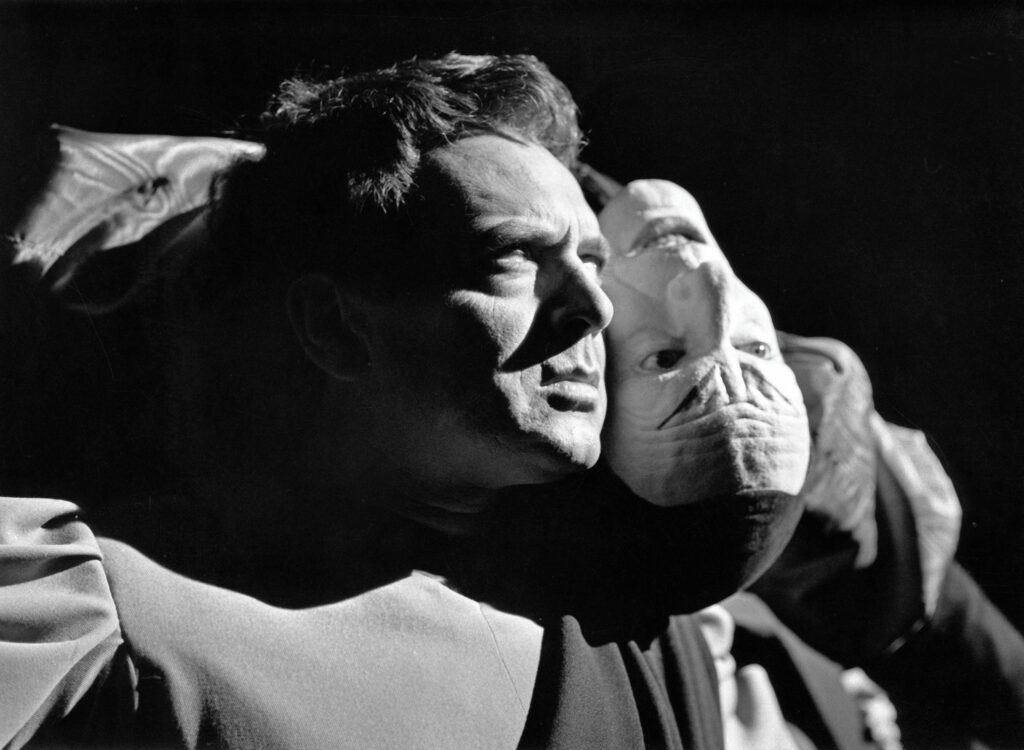

Take, for example, the way Huebert writes about oil. “The oil pumping through the Streamline refinery used to be life,” one character notes, “plants and animals, microfauna and zooplankton stewed for hundreds of millions of years in gaseous chambers in the bottom of the earth.” Huebert never loses sight of the fact that the substance that fuels our internal combustion engines literally comes from the sludgy corpses of our ancestors. There is something gothic about petroleum, something transgressive and evil and seductive. As the narrator of the titular story, a chemical engineer who spends his time off caring for his chronically ill wife, Eileen, puts it: “Say what you want about oil but the way Eileen described it she always made it seem beautiful: dense and thick, a million different shades of black.” Hydrocarbons are the Faustian energy source, bewitching and empowering, that allowed humans to tame the laws of physics, to fly through the air and send rockets to the moon. But there is no Faust without Mephistopheles, and the bill is coming due. What is to be done?

The bill is coming due.

From Faust, 1960; United Archives GmbH; Alamy

Huebert doesn’t provide any easy answers. His characters all understand that they live in a sick society, but they’ve got the sickness, too. The apparently sane narrator of “Chemical Valley” keeps his decomposing mother in a muskeg pit in his basement. The student activists in “Oilgarchs” and “Swamp Things” become disillusioned with non-violent protest, but their forays into vigilantism are no less impotent. The hockey player in “Six Six Two Fifty” is a gentle goon who can keep his job only by periodically mashing his opponents to pulp for the amusement of the rubes. “Desert of the RL” features a teenage girl whose relationship to a much older man turns out to be problematic but also based on a fantasy. In “SHTF,” the narrator’s partner becomes a doomsday prepper, pouring money into gear he hopes will give him an edge when the shit hits the fan. The penultimate story, set in a nursing home at the beginning of the pandemic, is an understated reminder that the actual collapse of society will be boring as well as terrifying. In these tales, knowing what’s really going on doesn’t make you good, it makes you crazy.

Yet Chemical Valley stubbornly refuses the comforts of nihilism. Huebert’s characters may live in a decaying world, but they still have to live. This moral vision finds its crystalline articulation in “Cruelty,” about an exhausted new mother named Deepa whose home is invaded by mice. She knows the rodents spread toxins that could kill her infant daughter, but she can’t bring herself to hire an exterminator who uses poison. Instead, she tries to engage a more expensive, cruelty-free pest control service operated by a man who seems to be everything her distracted husband, Dan, isn’t. The catch is that she’ll need to sleep with this guy, which she both does and does not want to do. There is an echo of Lovecraft in her growing obsession with the mice in the walls that gives the story a sense of anxious claustrophobia as well as an exquisite sexual tension that is domestic and dangerous. The narrative ends on a note of high irony: Dan, who finally takes some initiative, brings home a kitten they call Hunter. Lying in bed, Deepa muses that the cat is “not an end of hurt, but a movement of it.” In the world of Chemical Valley, that’s about all you can hope for.

André Forget is the author of In the City of Pigs. His new Substack is called Oblomovism.