Prime ministers are not exactly in fashion. In 2016, for example, Wilfrid Laurier University reversed its decision to house twenty-two life-sized statues of them after critics called the Canada 150 project “culturally insensitive.” Two years later, Victoria mothballed its statue of Sir John A. Macdonald, citing his central role in the creation of residential schools. Regina, Charlottetown, and Kingston followed in rapid succession. Toronto’s remains standing in Queen’s Park, but it’s covered up. Elsewhere, protesters took matters into their own hands, pulling the Old Chieftain fraom his pedestals in Montreal’s Place du Canada and Hamilton’s Gore Park.

Michael Hill got the proverbial memo on prime ministers, Indigenous peoples, and reconciliation, and he acknowledges in the opening pages of The Lost Prime Ministers that First Nations and Métis communities paid a disproportionate price in the making of this country. But that’s as far as he goes.

Insisting that prime ministers are self-evidently important and that their lives are convenient frames for organizing and explicating larger events and perennial themes in Canadian history and politics, Hill has written a collective biography of four men who briefly occupied the office. If biographies are fun to read, they are hell to write — or at least to write well. As every biographer knows, the challenge is one of balancing: in this case, the men and their times, or what Donald Creighton once called character and circumstance.

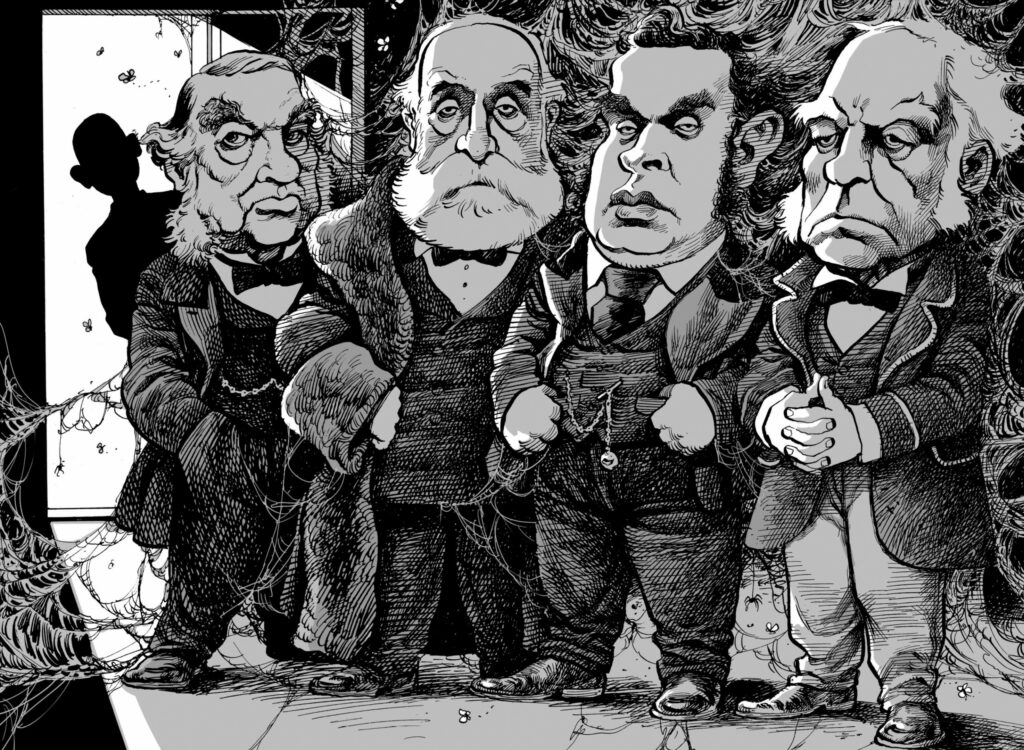

Hill starts from the premise that the four individuals who succeeded Macdonald, after his death in 1891, have been largely forgotten, despite getting to the top of the political greasy pole. Point taken. Before reading The Lost Prime Ministers, I could name only John Thompson, the first Catholic prime minister — and I have a doctorate in Canadian history! In Right Honourable Men, from 1994, Michael Bliss devoted less than a page to Abbott, Thompson, Bowell, and Tupper. In Mr. Prime Minister, from 1964, Bruce Hutchison was more generous, extending a short chapter to these prime ministerial footnotes. One resigned due to ill health (Abbott); one died in office (Thompson); and two flamed out (Bowell, whom Hutchison unfairly dismissed as a “tiny, stupid man,” was compelled to resign, while Tupper, who kept his black doctor’s bag under his seat in the House of Commons, was defeated at the polls).

Dusting off a few forgotten figures.

David Parkins

A lovely writer, Hill paints compelling biographical sketches. John Abbott, for instance, was the first Canadian-born and first bilingual prime minister. And he had a wide range of interests, from music, orchids, and Guernsey cattle to law, business, and politics, which he apparently hated. When Lord Stanley invited him to form a government, Abbott, then a senator from Quebec, knew that the call had come because he was, in his words, the “least loathsome” to a party divided along religious, linguistic, and sectional lines. He was also seventy years old, and sixteen months after being sworn in, he was diagnosed with a brain tumour, or what doctors in London described as “brain congestion and consequent exhaustion of the brain and nervous system.”

By comparison, John Thompson was a much younger man — becoming prime minister at just forty-seven — but he was a Catholic. Worse, Sir John the Lesser, as he was nicknamed, was a “pervert,” according to Lady Macdonald, meaning he had converted to Catholicism. Overwork and lack of exercise took their toll, and two years later Thompson, reporting chest pains, dropped dead in Windsor Castle after an audience with Queen Victoria.

The reins fell to Mackenzie Bowell, a newspaperman from Belleville, Ontario, and an Orangeman, who once served as grand master of the Orange Order of British North America. Like Abbott, he was a senator, and like Thompson, he had an unusual capacity for hard work. But he could be cold, and, as a result, he struggled to cultivate loyalty. When seven cabinet ministers resigned over Bowell’s handling of the Manitoba Schools Question, he did too. (In 1890, the Manitoba government precipitated a political and constitutional headache for the federal government when it ended the province’s dual school system — one English and Protestant, the other French and Catholic — and created a single system that was English and non-denominational.)

It would be up to Charles Tupper — the “Great Stretcher” (of the truth) from Cape Breton — to lead the Conservatives into their long political sunset a few months later, although it must be said in his defence that the Tories won a majority of the popular vote in 1896.

As good as his sketches are, Hill isn’t a historian, and it shows. Put another way, if he hit character, he missed circumstance. Relying on the research of Carman Miller (Abbott), Peter Waite (Thompson and Bowell), and Phillip Buckner (Tupper), The Lost Prime Ministers is potted at best and cribbed at worst. It’s too bad, because Hill had a chance to explore why prime ministers are . . . well, unfashionable, to say the least.

As government leader in the Senate, Abbott moved the second reading of an 1887 amendment to the Indian Act to restrict Indigenous people from cutting valuable trees for firewood — pine in particular. “It is found,” he reported, “that those Indians are reckless and that they destroy any amount of timber to burn it.”

A year later, he went further. In a debate on “Destitution among the Indians,” Abbott defended the government’s answer to the “Indian question” in the North‑West. Although steps had been taken, he said, to “gradually wean the Indians from the life of improvidence to which they are accustomed,” it was an uphill battle. “Of all the savage or semi-savage races in the world the North American Indians are the most criminally improvident.” Indeed, they would “not take the trouble to provide themselves with the food lying at their feet for the wants of the next day, and naturally they fall into these periods of starvation and hardship, which a little more prudent disposition would enable them to avoid.” In short, their destitution was their own fault.

Drawing on the racist caricature of the “drunken Indian,” Abbott insisted that individual land ownership was not in the cards because speculators “would go round among the Indians and buy their farms for a few glasses of whiskey.” Still, progress was being made, he said, “to lead these Indians into more provident and industrious habits.” In fact, “they now have schools for their children.” (Montreal’s John Abbott College may find itself in the same boat as Ryerson University, recently renamed Toronto Metropolitan University.)

As Macdonald’s newly appointed minister of justice, Thompson forcefully defended the government’s decision not to commute Louis Riel’s sentence of execution, which earned him the appreciation and even affection of his boss. Although Hill summarizes Thompson’s two-hour speech — another biographer maintained that it was four hours! — in the House of Commons in 1886, he doesn’t quote from it. Indeed, his summary follows J. Castell Hopkins’s 1895 summary, suggesting he didn’t read the long oration. For the record, here is part of what Thompson said:

How could the punishment of the law have been meted out to them, or any deterrent effect have been achieved, if the “arch conspirator,” the “arch traitor,” if the “trickster,” as he has been called by men who did him their best service, was allowed to go free or kept in a lunatic asylum until he chose to get rid of his temporary delusions? It was absolutely necessary, as I have said, to show to those people, to those Indians, and to every section of the country, and to every class of the population there, that the power of the Government in the North‑West was strong, not only to protect but to punish.

In other words, Indigenous people had to be shown the power and majesty of the law and the determination of the state.

Bowell also answered the “Indian question” when, in 1893, a long-running dispute over a reserve in Victoria came across his desk as government leader in the Senate. A colleague from British Columbia wanted to know what the government intended to do about the Songhees living on the shoreline of the city’s inner harbour. Citing “habits of drunkenness and immorality” in and around the area, William Macdonald insisted that the time had come for “these Indians” to be “removed.” To be sure, Bowell was a minor figure in the affair, but he agreed that relocation of the Songhees was in their best interest, which different levels of government conveniently got to define, adding that the existing reserve was an “injury” to Victoria’s “improvement” and “extension.” Racism, paternalism, and not least greed would lead to the community’s eventual removal in 1911 and to what the historian Jean Barman calls the “erasure of urban Indigenous space” in British Columbia.

When Bowell was prime minister, his government amended the Indian Act in 1895 to expand its prohibition of Indigenous religious and cultural practices. Going forward, it would ban “any Indian festival, dance, or other ceremony” in which “giving away” was a feature: that is, the sun dance and thirst dance in the three Prairie provinces and the potlatch and the tamanawas in British Columbia. (Consisting of “orgies of the most disgusting character,” the tamanawas led to “much demoralization.”) As Bowell told the Senate, it was “better to prohibit all giving-away festivals, as they are conducive of extravagance, and cause much loss of time and the assemblage of large numbers of Indians, with all the usual attendant evils.”

None of this is to suggest that we shouldn’t write biographies of prime ministers, because of course we should. Again, Hill is a good writer, and I learned a lot, especially about the importance of religion in late nineteenth-century politics. Nor is it to suggest that when we do undertake such projects, we need to write black-armband biographies. Canada’s lost prime ministers were, after all, accomplished men who led interesting lives. Still, I wish that Hill had paid closer attention to that memo.

Donald Wright chairs the political science department at the University of New Brunswick and is the co-editor of Acadiensis.

Related Letters and Responses

Hamar Foster Victoria

@trunge1 via Twitter