When the science writer and occasional CBC personality Britt Wray started thinking about having a child — a desire she felt deep in her bones — she experienced an unexpected “sense of grief and despair.” What would it mean to bring new life into the world when our leaders are “walking with open arms into ecological dead zones”?

Reproductive anxiety is just one of the many forms of so-called eco-distress discussed in Generation Dread: Finding Purpose in an Age of Climate Crisis. In 2021, Wray conducted a global survey of 10,000 people aged sixteen to twenty-five and found that 45 percent had experienced a negative impact on daily activities like eating, concentrating, and maintaining relationships. Almost 40 percent indicated “they were hesitant to have children.” Overall, the mental health effects of ecological destruction are on the rise. According to a British poll from 2020, young people were “more worried about the climate crisis than they had been just one year prior.”

“This book,” Wray states at the outset, “is not a manual for how to take effective climate and environmental action.” Instead, she draws from extensive research, her own emotional journey, and the personal stories of others to demonstrate psychologically healthy ways to manage eco-distress. She wants to help people find meaning and thrive so they can, in turn, help those who are dealing with immediate threats such as floods, droughts, wildfires, and health problems.

One of the book’s more moving anecdotes is the story of Charlie Glick, a young man living in California, who was so overwhelmed by climate despair that, in 2020, he abandoned a promising music career. For months, he worked with a climate-conscious therapist and connected with groups where he could share his distress. The emotional work of acknowledgement and acceptance — what the psychotherapist Caroline Hickman calls “internal activism”— eventually gave Glick greater perspective. “Though external activism would have been a noble pursuit,” Wray explains, “for now Charlie had found meaning in a much quieter act”: moving in with and caring for his ninety-four-year-old aunt.

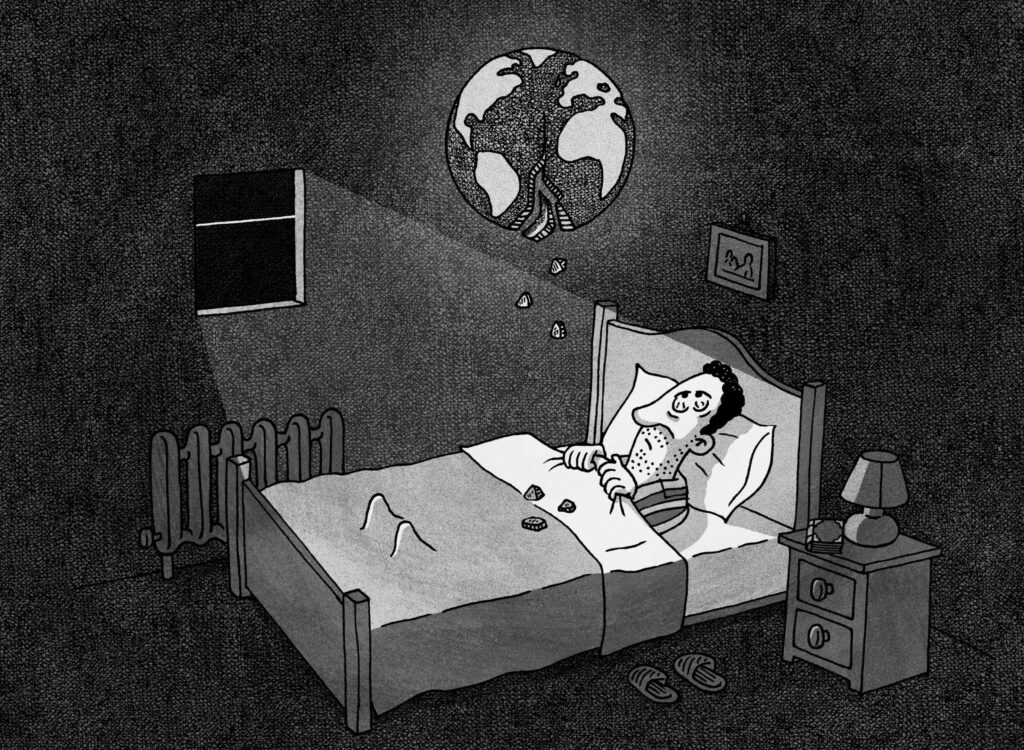

As the planet comes apart at the seams.

Tom Chitty

Generation Dread presents another encouraging example in Jennifer Atkinson, an English professor in Seattle. In 2017, Atkinson registered an increasing sense of despair among her students, particularly those majoring in science. “Why should I go to school when there won’t even be a future with a job for me to work in,” they asked. She decided to design a course “that addresses the emotions of environmental work” through the disciplines of literature, history, philosophy, and cultural studies. The class was immediately popular and “has run at full capacity ever since.” One student evaluation spoke of a personal transformation from a state of “powerlessness and hopelessness” to one in which it is “possible to feel those things and not completely give up.”

Whether for an individual like Charlie Glick or a room full of science majors, healing occurs within communities. Wray is acutely aware of inequalities in access to help, and she hopes that her work “can contribute to us getting better at looking out for each other.” In order to improve our odds of collective survival, she argues, we must move toward a “partnership-oriented” model of society that “values egalitarian, life-sustaining structures and mutually supportive systems.” She describes how neighbourhoods that come together to identify and respond to local “priority areas”— by growing food, setting up supports for the next heat wave, or cleaning up waste — are more equipped to organize when disaster strikes. Communities still “need governments and institutions to support them,” of course. But Generation Dread stops here: the step-by-step challenges of bringing about systemic change and building more resilient foundations are a topic for another book.

Where Wray wants readers to transform eco-distress into inner strength and local unity, the journalist Chris Turner finds hope for “the dawn of a new age.” With How to Be a Climate Optimist: Blueprints for a Better World, he seeks to spread the good news: renewable energy installations, the adoption of electric cars, and updates to building codes are all coming along faster than anyone expected a decade ago. Still, he admits, the transition is long overdue and far too slow.

The greatest obstacle facing an energy revolution is the lack of political will. Turner saw this first-hand when he learned of a proposal for a mixed-use development in his Calgary neighbourhood not far from Scotsman’s Hill. Initially full of excitement about the plan’s sustainable design, he quickly realized several residents were pushing hard against it because “the new towers would cast shadows over their roofs — which, they claimed with straight faces, they might one day want to cover with solar panels.” When it comes to climate-friendly initiatives, he concludes, “the ones who really don’t want it” are often more prepared to “take aggressive action than the ones who think it would be fine.”

Ultimately, the initiative was scrapped because of an economic downturn. But the lesson remains: opponents will fight a climate-friendly project if they believe it involves sacrifice on their part. It’s not enough to have the best idea. You have to find a way to win people over.

To that end, Turner takes a cue from the world of marketing: he offers a “value proposition” for the energy transition. With solar panels, for instance, “homes can now be power plants” that sell electricity back to the grid and deliver a profit to the owners. Similarly, neighbourhoods that are walkable and “built to human scale” can be advertised as more sustainable and vibrant (and presumably enjoying higher property values). But How to Be a Climate Optimist doesn’t show how the new value proposition has changed any minds. The theory is intriguing, but it remains untested.

Elsewhere, Turner grounds his vision in reality, as when he recounts an experience in Copenhagen, a lively city that epitomizes sustainable urban design. While there, he visited a friend. The two met up, enjoyed some wine on a cozy patio, and later hopped on their bikes. Cycling infrastructure in the Danish capital is so well designed that their ride was “as safe as walking, even after a few glasses of the house red.”

How to Be a Climate Optimist is not always convincing. For example, Turner remains confident that we will keep global warming at a level below 2 degrees Celsius, which he admits is still dreadful but would avoid the most apocalyptic of outcomes. In April of this year, the journal Nature suggested a vision like Turner’s is still feasible, but it “urgently requires policies and actions to bring about steep emission reductions this decade.” Keeping warming in check is a key part of Turner’s optimism — and of his excitement. He believes this could well be “one of the most amazing collaborative projects” in human history. Given current geopolitical tensions, however, such global cooperation in the next ten years seems a debatable prospect, at best.

Turner’s efforts to instill confidence are understandable. “People, masses of them,” he writes, “don’t build something much better in panic and terror.” But real optimism requires a solid foundation of reasoning. Because Turner’s hope depends on many uncontrollable factors, it feels like a foundation of sand, vulnerable to every inimical shift.

Andrew Torry is a writer and curriculum designer in Calgary.