To establish the relationships that sustain the city’s life, the inhabitants stretch strings from the corners of the houses, white or black or gray or black-and-white according to whether they mark a relationship of blood, of trade, authority, agency. When the strings become so numerous that you can no longer pass among them, the inhabitants leave: the houses are dismantled; only the strings and their supports remain.

— Italo Calvino

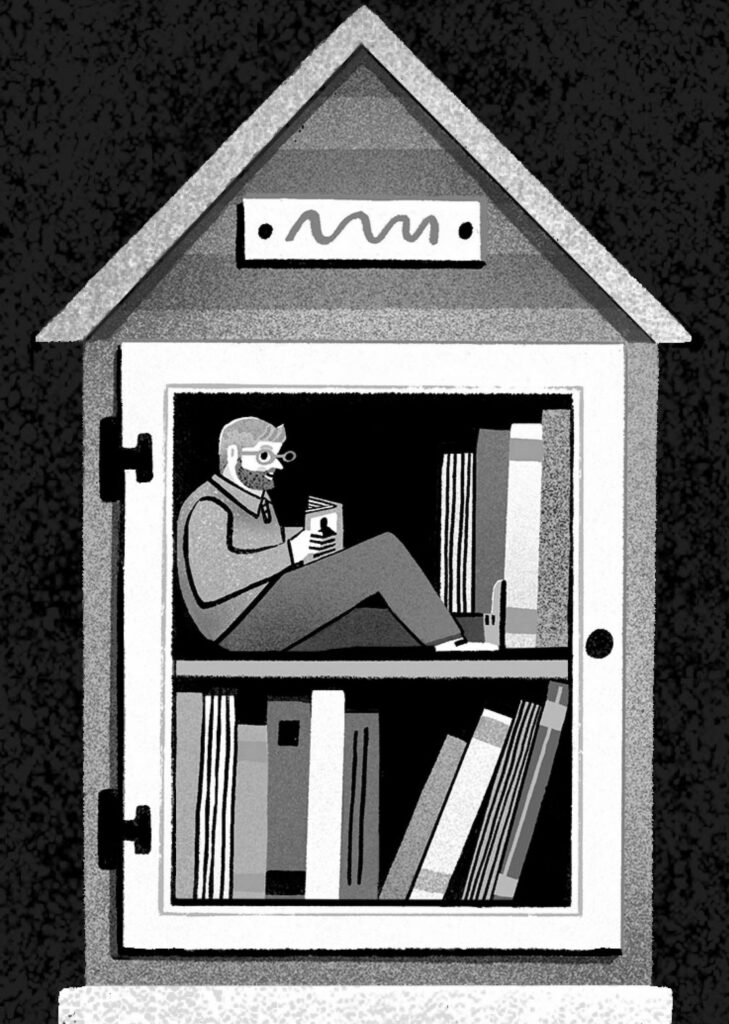

They look like those altars to the Virgin Mary that you often see along the streets of Mexico, where worshippers lean in and pause for a moment and hope. Here, the worshippers also stop to peer in, but then they rummage around, and if they’re lucky, they leave with a book.

The past few years have seen book boxes proliferate across North American cities. The Little Free Library, the largest organization devoted to book boxes, claims there are over 150,000 in the United States. In Montreal, they have been appearing on street corners, in front yards, and in back alleys. Valérie Plante’s mayoral administration has accelerated the trend. Some boxes follow the approved municipal design — a purposely off-kilter trapezoidal shape with a glass door — while others are the product of individual handiwork, all bright colours and reused wood. No online map will give you their location. The city website does not list them. They are features of the urban landscape, like a handsome street light or a thriving flower bed, known only to the local and the flâneur.

I have become enchanted with the book boxes. I try to pass it off as academic interest, but it’s more than that. I get skeptical looks when I mention the boxes to friends, who dismiss them as repositories of self-help paperbacks and programming textbooks for dead computer languages. They’re not wrong: there is always a permafrost layer of old astrology manuals. But some days fortune strikes, and one finds a gem lying on top. I live for those days.

Taking comfort in non-curated randomness.

Sandi Falconer

Those used to be rare events. Then, at the height of the pandemic, something happened. Suddenly, amid the discarded dictionaries, here was the year’s prizewinning poetry or the new Rachel Cusk novel everyone was talking about. Turnover soared. Sometimes a small queue would form. I recognized some of the regulars, pretending to check their phones while someone else had a look, taking turns peering in and praying. At times, the boxes became so full that a little pile of overflow formed at their base. In part, this was the result of an entire city stuck at home, reading. But there was more: COVID-19 generated an urge to reach out, to chip into collective enterprises, to give back. Didn’t people in Italy sing together on their balconies? In Montreal, they stuffed the books they’d finished reading into giant bird feeders in one another’s back alleys.

Once the tone was set, it proved rather self-sustaining. Outdated dictionaries no longer cut it. Instead, here were books one would give a friend. Meaningful books, favourite books. I felt the change operate within me. Coming upon an unsuspected pearl — a slim volume of Lucia Berlin stories or a collection of John Berger’s essays — I was overcome by the benevolence of the kindred spirit who’d dropped it off, a stranger I would never meet but who’d had a thought for me. What might they like in return, I wondered? I scoured my own shelves for anything worthy to offer in exchange, and I made daily pilgrimages to the little altars. I tried to read faster, to keep the books moving. I felt an urge to reciprocate, and I guessed at how others must have felt it, too. Social scientists call this the “collective-action heuristic.” It’s that impulse to participate when you see others doing the same. It’s what fuels charitable giving and communal gardens — as well as protest marches and insurrections.

In the thick of lockdown, the book boxes saved me. In search of pretexts for my solitary walks, I would leave home with an armful and complete a wandering circuit around the four boxes of the Plateau neighbourhood. I came to know the idiosyncrasies of each: Rue Prince-Arthur’s predilection for the 1960s Québécois golden age, fed by the Maison des écrivains in the Carré St-Louis. The heavy Spanish-language rotation on Avenue Duluth. The ecology-inclined offerings on Roy, near the Santropol community food hub. Sometimes I took a book and moved it to the box I knew it was meant for. In the first months of the pandemic, when no one was sure of what we were dealing with, I quarantined my finds, leaving them overnight at the bottom of the stairs before bringing them into the apartment.

In their humble way, the book boxes are an affront to modernity. They belong to a forgotten world, one where our phones did not yet claim to know the music we ought to listen to and the people we ought to go to bed with. The faithful who gather at these little altars really are believers of a sort. They believe in accident, in chance, in run-ins. They believe that a random title left by a random stranger can beat personalized algorithm-driven recommendations. And remarkably often, they’re proven right. The boxes have a way of capturing the zeitgeist in ways that defy explanation.

In a world of curated offerings, where recommendations are based on all the things we have already watched and read and listened to, the book boxes are one of the last bastions of non-curated randomness. During the height of the pandemic, especially, when predictability and routine came to dominate, the book boxes remained all dark, unguessable potential. Mostly flotsam, occasional godsend. I owe a lifelong debt to such randomness. As it happens, this is how I met my life partner — by chance. Being of a generation that just barely avoided the ubiquity of dating apps, we joke that no artificial intelligence would ever have matched us. We are too different, too obviously ill-suited for one another. We, too, are an affront to the algorithms.

In A Treatise of Human Nature, David Hume, the pre-eminent figure of the eighteenth-century Scottish Enlightenment, distinguished between “two different sorts of commerce, the interested and the disinterested.” Disinterested commerce was the older kind. It relied on natural feelings of obligation arising from shared sympathy, as one might expect between friends. But in a modern society, Hume recognized, most human dealings took place between strangers, arising not from gratitude but from the expectation of some “mutual advantage.” Such interested commerce relied on promises, contracts, and formal enforcement.

Hume had no illusions about human nature; after all, he wrote the book on it. “Men being naturally selfish, or endowed only with a confined generosity, they are not easily induced to perform any action for the interest of strangers, except with a view to some reciprocal advantage.” Yet he held out hope that even as “this self-interested commerce of men begins to take place, and to predominate in society,” it would “not entirely abolish” what he called its “more generous and noble” counterpart.

What Hume sensed even then, and what sociology has since confirmed in one of its most established findings, is that the newer, self-interested commerce is actually propelled by that older, more generous type. Societies that prosper tend to be those that exhibit higher levels of generalized trust and a propensity toward relations of the disinterested sort, the ones usually associated with the sphere of friendship. It turns out that for-profit enterprise grows more readily in settings where people already display greater trust toward strangers. The willingness to perform services for others without any guarantee of repayment is now referred to as “social capital.” The term stands for the range of connections that link the people living in a given place, as well as the norms of reciprocity that arise from those networks. It can be measured through pro-social behaviour like volunteerism, voting turnout, blood donation — and, I’m tempted to add, book box turnover.

A couple of decades ago, the study of social capital was all the rage among political scientists. Academic trends come and go, much like tastes in fashion. The vogue for social capital peaked and ebbed roughly alongside that of skinny jeans, reaching its heyday circa 2005, a few years after the Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam published his bestseller Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. In it, Putnam argued for the value of social capital and charted its steady decline across industrialized societies. Throughout the postwar period, he claimed, people were living increasingly atomized lives and gradually growing distrustful of one another. The result was a decline in the type of participatory behaviour one associates with thriving democratic societies.

The study of social capital is now experiencing another boom. The pandemic has put collective trust and social cooperation in the foreground once more. Public health measures, it turns out, rely on people’s willingness to put up with discomfort, isolation, and needles, largely for the sake of others. A string of studies has shown how higher social capital was a factor associated with fewer COVID-19 infections and deaths.

In a market society like ours, where we are incentivized to get ahead at one another’s expense, one might think there would be no place for the selfless barter of the book boxes. Hoarders would quickly outnumber contributors; profiteers would clue in, and the richest pickings would soon end up in the city’s second-hand bookshops. Shouldn’t interested commerce swallow its gullible sibling whole? Yet the logic of disinterested commerce has survived alongside its interested counterpart. The book boxes not only endured; they thrived just as the city faced its greatest challenge, as everything that defined it — its nightlife, its crowded public spaces, its cultural production — was suspended for months on end.

Lockdown ended long ago, of course, and the turnover at the book boxes has predictably decreased. The city’s bars and restaurants are once more packed; people are no longer stuck at home wrestling with Proust. Yet just as book sales rose during the pandemic — especially at independent shops — and have yet to come down to pre-pandemic levels, the habits of the book box worshippers seem to have become set for the long term. The shelves continue to fill up and empty, and occasionally gems can still be found lying on top.

These are ramshackle wooden boxes often stocked with outdated textbooks. But at their best, they are also odes to randomness, evidence of people’s willingness to ignore the market’s logic and reach out to strangers they will never meet. They are templates for social experimentation yet to come. In their small way, they gesture toward what might be possible in the post-pandemic city. Whenever I pass one, I can’t help but pause, peer inside, and hope.

Krzysztof Pelc is a professor of political science and international relations at McGill University.